HINES, IL—Older age, obesity and Agent Orange exposure create a trifecta of diabetes risk for the VA.

Nearly 25% of veterans have diabetes, making efficient and effective management of their care a top concern for the department, particularly as helping veterans get and keep their blood glucose levels at safe levels requires frequent healthcare visits. Failure to manage those levels sharply increases the risk of cardiovascular disease, chronic kidney disease, ophthalmological issues, neuropathy and death and significantly increases the cost of care.

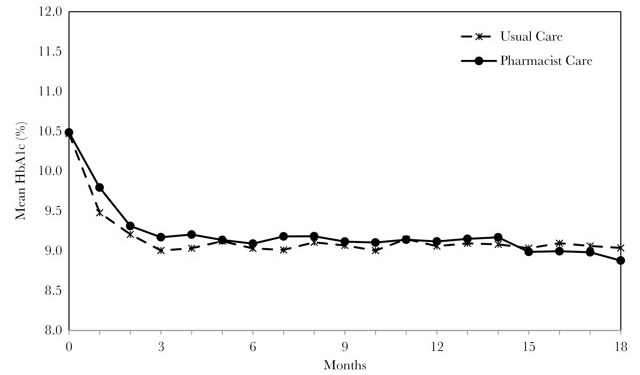

Mean glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) values over time in the study groups.

American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, Volume 76, Issue 1, 1 January 2019, Pages 26–33, https://doi.org/10.1093/ajhp/zxy004

That combination creates a bit of a bind for VA physicians, according to Anthony Morreale, PharmD, the VA’s associate chief consultant for clinical pharmacy services and healthcare based in Hines, IL. “Physicians will make a diagnosis and start a patients on medication, but they don’t have enough clinic spots to titrate patients regularly to get them to goal. On average, they can only see patients twice a year. If you have a panel size of 1,200 and see each twice a year, that’s all the spots available.”

Increasingly, clinical pharmacy specialists fill the gap, helping veterans adjust their medications and manage any side effects. According to a recent study published in the American Journal of Health-System Pharmacy, veterans fare at least as well when clinical pharmacists manage their care as when physicians do and, by some measures, have even better outcomes.1

Clinical pharmacy specialists have been helping manage care of diabetic veterans since the 1990s. Today, diabetes management is the No. 1 reason for patient referral for CPS care, Morreale told U.S. Medicine.

Finding that veterans do well under the care of a clinical pharmacy specialist “was not a big surprise to us, but this was one of the first times we had the data and methodology to track the outcomes,” noted Morreale, a co-author of the study.

The study compared care provided by CPSs to usual diabetes care in 53 VAMCs for veterans who had baseline glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) values greater than 9%. The research team analyzed 12,327 patients referred to pharmacists for management to a propensity score matched group of the same size managed by physicians.

Veterans in the pharmacist-managed group achieved HbA1c values of less than 8% and less than 9% in less time than those in the usual care group. At six months, 46% of veterans in the pharmacist-managed group had blood glucose values under 9%, and 22% had HbA1c under 8% compared to 38% and 20%, respectively, of those receiving usual care. At 12 months, patients were 37% more likely to achieve HbA1c levels below 8% and 54% more likely to have levels below 9% if they were managed by pharmacists.

“If physicians are trying to manage these patients on their own, it’s no surprise we get to goal quicker and have more visits with patients,” Morreale said. “Most of our visits are remote. Clinics aren’t filled up with patients waiting for us to titrate them; the vast majority of the visits are done by phone.”

The expertise and focus of pharmacists also makes a significant difference. “The bottom line is that pharmacists have specific expertise in management of those medications, their side effects, and adherence issues. It’s our primary responsibility,” Morreale added.

“If a patient goes to a primary care visit, they may have six issues on their care list, and the physician might not have time to address them all,” he noted. “Pharmacists are very focused that that’s the right medication and that it’s titrated properly, while a primary care provider is trying to balance five things simultaneously.”

By working as part of a care team, clinical pharmacy specialists can free up physicians to diagnose new cases and manage complications. While adjusting diabetes medication, pharmacists might also adjust lipid and hypertension therapies as well further reducing calls and visits to physicians, Morreale said.

Clinical pharmacy specialists can provide the greatest value to veterans and care teams when they are applying their clinical skills to manage pharmacotherapy. “About 27% of visits to primary care could be done by pharmacists and about one-third are following up on medications, titration, side effects and the like,” Morreale observed.

Setting Goals

The study found that about 17% of veterans in the pharmacist care group and 14% of those in the usual care group had HbA1c values below 7%. About equal percentages of those with HbA1c below 7% who were taking insulin or secretagogues in both groups had risk factors for hypoglycemia. Both groups also had about the same number of patients with HbA1c below 6% who were prescribed insulin or secretagogues.

Serious hypoglycemia requiring hospitalization or an emergency department visit occurred somewhat more often in the pharmacist-managed group than in usual care, 4.3% vs. 3.1%.

“Obviously, evidence shows that lower A1c levels can be indicative of overtreatment and can increase risk of hypoglycemia,” said lead author Heather L. Ourth, PharmD, VA’s national program manager for Clinical Pharmacy Practice Program and Outcomes Assessment. “We could not determine how many patients had harder to manage disease which might require insulin or whether their medications were adjusted after they achieved levels of 6% or 6.5%.”

Attending to the risks of hypoglycemia has been a priority for the VA and for its clinical pharmacists.

“We strive to obtain the maximum clinical benefit while minimizing adverse events from the drug,” said Morreale. “That means making sure we customize the dose for what the patient needs, their age, and what they want to achieve. The American Diabetes Association and other metrics can have unintended consequences. For many patients, an A1c of 7% is unrealistic and undesirable.”

- Ourth HL, Hur K, Morreale AP, Cunningham F, Thakkar B, Aspinall S. Comparison of clinical pharmacy specialists and usual care in outpatient management of hyperglycemia in Veterans Affairs medical centers. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2019 Jan 1;76(1):26-33.