Major Cardiovascular Events

In this study, researchers sought to compare major adverse cardiovascular events among patients with diabetes and reduced kidney function who continued treatment with metformin or a sulfonylurea.

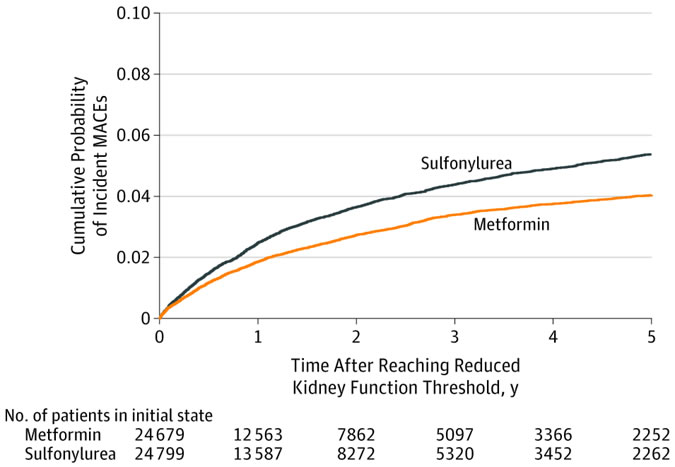

Association of Treatment With Metformin vs Sulfonylurea With Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events Among Patients With Diabetes and Reduced Kidney FunctionCompeting Risk Cumulative Incidence Match-Weighted CohortAalen-Johansen cumulative probability of incident major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) among sulfonylurea vs metformin cohort with reduced kidney function. The median follow-up time in the weighted cohort was 1.0 year (interquartile range, 0.4-2.6) for patients taking metformin and 1.2 years (interquartile range, 0.5-2.7) for sulfonylurea users.

The retrospective cohort study used VA healthcare data supplemented by linkage to Medicare, Medicaid and National Death Index data from 2001 through 2016. It identified 174,882 persistent new users of metformin and sulfonylureas who reached a reduced kidney function threshold; that was defined as estimated glomerular filtration rate <60 mL/min/1.73 m2 or creatinine ≥1.4 mg/dL for women or ≥1.5 mg/dL for men.

The study team followed patients from reduced kidney function threshold until MACE, treatment change, loss to follow-up, death or study end in December 2016.

The focus was on new users of metformin or sulfonylurea monotherapy who continued treatment with their glucose-lowering medication after reaching reduced kidney function.

With 67,749 metformin and 28, 976 sulfonylurea persistent monotherapy users, the weighted cohort included 24,679 metformin and 24, 799 sulfonylurea users. The patients had a median age of 70 years [interquartile range {IQR}, 62.8-77.8]. The group was nearly all male and mostly, 82%, white with median estimated glomerular filtration rate of 55.8 mL/min/1.73 m2 [IQR, 51.6-58.2] and hemoglobin A1c level of 6.6% [IQR, 6.1%-7.2%] at cohort entry).

Metformin users were generally younger than sulfonylurea users—median age, 67 vs. 71 years—and a larger proportion of metformin users reached the kidney threshold in later study years.

During follow-up—a median of one year for metformin vs. 1.2 years for sulfonylurea—1,048 MACE outcomes occurred (23.0 per 1,000 person-years) among metformin users and 1,394 events (29.2 per 1000 person-years) among sulfonylurea users.

Researchers calculated that the cause-specific adjusted hazard ratio of MACE for metformin was 0.80 (95% CI, 0.75-0.86) compared with sulfonylureas.

“Among patients with diabetes and reduced kidney function persisting with monotherapy, treatment with metformin, compared with a sulfonylurea, was associated with a lower risk of MACE,” the authors concluded.

Researchers decried that clinical practice hasn’t kept up with evolving research in this area, pointing out that metformin often is discontinued in many patients when kidney disease develops. An article a few years ago in JAMA Internal Medicine reported that nearly 1 million U.S. patients with diabetes and eGFR between 31 and 89 mL/min/1.73 m2 could take metformin but do not.2

Underuse of metformin has continued, according to the study team, despite a Food and Drug Administration safety announcement more than three years ago to revise medical labels regarding metformin use in patients with reduced kidney function. The revised label states that metformin can be safely used in patients with mild kidney function impairment (45-60 mL/min/1.73 m2) and some patients with moderate kidney function impairment (eGFR, 30-45 mL/min/1.73 m2).

At the same time, the FDA also recommended that kidney function be evaluated with eGFR rather than creatinine. Study authors described how that guidance is now more in line with recommendations from the United Kingdom, Canada and Australia, which emphasize metformin use based on eGFR criteria rather than creatinine because eGFR more accurately measures kidney function.

The articles emphasized that patients with reduced eGFR may use metformin with frequent monitoring and dose reduction, but the drug remains contraindicated at an eGFR less than 30 mL/min/1.73 m2.

In an accompanying editorial, Deborah J. Wexler, MD, MSc of Massachusetts General Hospital and Harvard Medical School, described how sulfonylureas, including glyburide, glipizide and glimepiride, “have demonstrated glycemic efficacy, microvascular benefit and even potential long-term mortality benefit. While these medications are still recommended in World Health Organization guidelines ahead of newer glucose-lowering medications,4 the American Diabetes Association–European Association for the Study of Diabetes consensus report recommends sulfonylureas when cost is the primary consideration in medication selection.”3

Wexler noted that fears about cardiovascular risk associated with sulfonylureas tends to be related to excess cardiovascular mortality observed in a small number of patients treated with a first-generation sulfonylurea, tolbutamide, compared with placebo. The finding has remained controversial since the 1970s, she wrote.

Although Wexler advised, “The study further supports the use of metformin as the first-line treatment to which other diabetes medications are added, even as early chronic kidney disease develops,’ she also recommended against discontinuing use of sulfonylureas.

Until the conclusion of ongoing studies which could affect therapy options, she suggested, “In the meantime, clinicians can continue to use low-cost sulfonylureas added to metformin for management of hyperglycemia in Type 2 diabetes with confidence in their effectiveness for reduction of microvascular complications as well as their cardiovascular safety. The adverse effect profile of sulfonylureas and their very low cost must be balanced against characteristics of other glucose-lowering medications as clinicians consider the best approach for an individual patient.”

- Roumie CL, Chipman J, Min JY, et al. Association of Treatment With Metformin vs Sulfonylurea With Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events Among Patients With Diabetes and Reduced Kidney Function. Published online September 19, 2019322(12):1167–1177. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.13206

- Flory JH, Hennessy S. Metformin use reduction in mild to moderate renal impairment: possible inappropriate curbing of use based on food and drug administration contraindications. JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(3):458-459.

- Wexler DJ. Sulfonylureas and Cardiovascular Safety: The Final Verdict? 2019 Sep 19. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.14533. [Epub ahead of print] PubMed PMID:31536110.