VA Participates in Large Study to Assess Best Second-Line Treatment

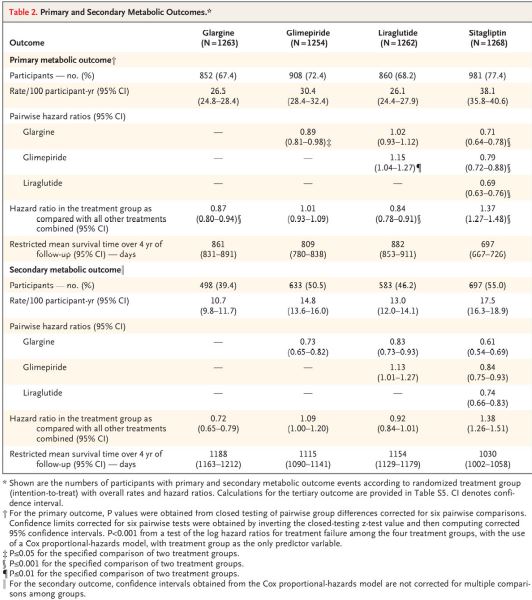

Click to Enlarge: Primary and Secondary Metabolic Outcomes.* Source: New England Journal of Medicine

ROCKVILLE, MD — Clinicians treating Type 2 diabetes have an arsenal of medications to help lower glucose levels in patients with uncontrolled blood sugar. The key question regards which work best to lower glucose levels and keep them low.

That issue was addressed in a recent study involving VA researchers. The Glycemia Reduction Approaches in Diabetes (GRADE) study group, based at George Washington University, examined the comparative effectiveness of glucose-lowering medications for use with metformin to maintain target glycated hemoglobin levels in Type 2 diabetes patients.

Researchers from VAMCs in Cincinnati; Seattle; Aurora, CO; and Cleveland participated in the study with a range of other academic institutions.

In the study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, about 5,000 participants had T2D with less than 10 years’ duration, were receiving metformin and had glycated hemoglobin levels of 6.8 to 8.5%. Researchers compared the effectiveness of four commonly used glucose-lowering medications.1

Participants were randomly assigned to receive:

- insulin glargine U-100 (hereafter, glargine),

- the sulfonylurea glimepiride,

- the glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist liraglutide, or

- sitagliptin, a dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitor.

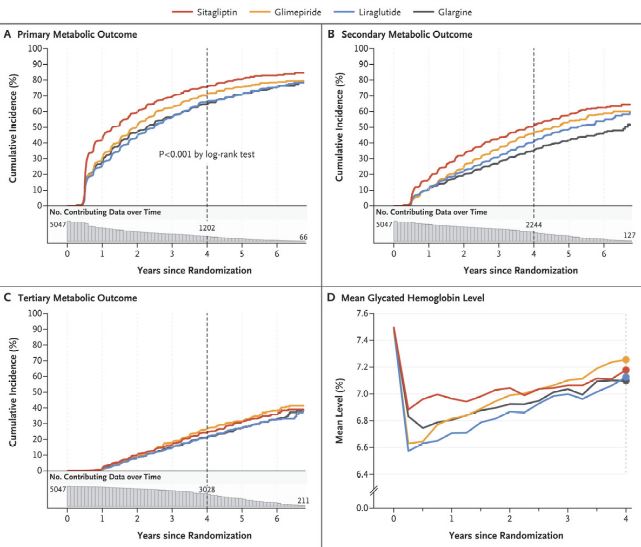

Defined as the primary metabolic outcome was a glycated hemoglobin level, measured quarterly, of 7.0% or higher that was subsequently confirmed, and the secondary metabolic outcome was a confirmed glycated hemoglobin level greater than 7.5%.

The 5,047 patients—19.8% Black and 18.6% Hispanic or Latinx, with the rest white—were followed for a mean of five years. “All four medications, when added to metformin, decreased glycated hemoglobin levels,” the authors pointed out. “However, glargine and liraglutide were significantly, albeit modestly, more effective in achieving and maintaining target glycated hemoglobin levels.”

“The cumulative incidence of a glycated hemoglobin level of 7.0% or higher (the primary metabolic outcome) differed significantly among the four groups (P<0.001 for a global test of differences across groups); the rates with glargine (26.5 per 100 participant-years) and liraglutide (26.1) were similar and lower than those with glimepiride (30.4) and sitagliptin (38.1),” according to the researchers. “The differences among the groups with respect to a glycated hemoglobin level greater than 7.5% (the secondary outcome) paralleled those of the primary outcome.”

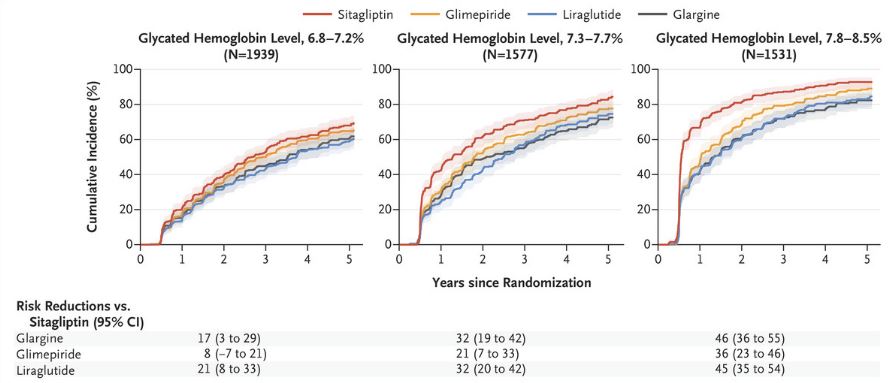

The study found no meaningful differences to the primary outcome according to sex, age or race or ethnic group. Participants with higher baseline glycated hemoglobin levels, however, appeared to have an even greater benefit with glargine, liraglutide and glimepiride, compared with sitagliptin.

The authors noted that severe hypoglycemia was rare but significantly more frequent with glimepiride (in 2.2% of the participants) than with glargine (1.3%), liraglutide (1.0%) or sitagliptin (0.7%). Patients who received liraglutide reported more frequent gastrointestinal side effects and lost more weight than those in the other treatment groups.

Significant Findings

The findings are significant because Type 2 diabetes affects more than 30 million adults in the United States and more than 500 million worldwide, with an annual incidence in the United States of approximately 1.5 million cases. At the VA, an estimated one-fourth of veteran patients have been diagnosed with diabetes.

The authors explained that the disease’s “major human and economic costs are caused primarily by the development of diabetes-specific complications, including retinopathy, nephropathy, and neuropathy, and a risk of cardiovascular disease that is two to five times as high as that among persons without diabetes.”

On the other hand, they added that those long-term diabetes-specific complications can be ameliorated by interventions that decrease chronic glycemia, as measured by glycated hemoglobin levels, adding that a target glycated hemoglobin level of less than 7.0% (<53.0 mmol per mole) is generally considered to decrease morbidity.

The challenge for clinicians is that, while nearly all recommendations for the management of glycemia in Type 2 diabetes patients include metformin as the first-line medication. The second medication added when needed to achieve or maintain a glycated hemoglobin level of less than 7.0% is less clear.

“Unfortunately, there are few long-term comparator studies to guide the choice of a second glucose-lowering medication,” the researchers wrote. “The purpose of the Glycemia Reduction Approaches in Type 2 Diabetes: A Comparative Effectiveness (GRADE) Study was to examine the relative effectiveness of agents from four of the most commonly used classes of glucose-lowering medications, when added to metformin, in achieving and maintaining target glycated hemoglobin levels in persons with recent-onset type 2 diabetes.”

Click to Enlarge: Analyses of the Primary Outcome According to Baseline Glycated Hemoglobin Levels. Source: New England Journal of Medicine

The authors also described how their overall results underscore the difficulty in achieving and maintaining recommended glycated hemoglobin levels in Type 2 diabetes patients. “In this diverse trial cohort, which included participants who were representative of those in the U.S. population who had metformin-treated Type 2 diabetes of brief duration, the mean baseline glycated hemoglobin level was 7.5% (range, 6.8 to 8.5),” they wrote. “During the mean 5-year follow-up, the target glycated hemoglobin level of less than 7.0% was not reached or maintained in 71% of the participants who received approximately 2000 mg of metformin per day plus one of four commonly used glucose-lowering medications.”

They added that, even among participants with an initial glycated hemoglobin level of 6.8 to 7.2%, a glycated hemoglobin level of less than 7.0% was not maintained in about h60% of them over the five-year follow-up.

Still, they pointed out that mean glycated hemoglobin levels decreased in all the treatment groups over the course of the trial. By the end of the trial, levels were approximately 0.3% lower than baseline levels.

Researchers also revealed other differences in efficacy and adverse effects among the four medications, all of which are Food and Drug Administration-approved and have acceptable safety profiles. Perhaps most importantly, the study found that glargine and liraglutide were more effective at maintaining glycated hemoglobin levels in the target range over the study period. “This translated into a glycated hemoglobin level of less than 7.0% for approximately a half year longer with glargine and liraglutide than with sitagliptin, which was the least effective treatment in maintaining target glycated hemoglobin levels,” the authors stated. “Glargine was most effective in maintaining the glycated hemoglobin level at 7.5% or lower, with only 39% of the participants having a glycated hemoglobin level greater than 7.5% (a secondary metabolic outcome event).”

Worse Outcomes

Click to Enlarge: Kaplan–Meier Analysis of Outcome Events and Mean Glycated Hemoglobin Levels. Source: New England Journal of Medicine

Another key finding was that participants with higher baseline glycated hemoglobin levels at baseline had progressively worse metabolic outcomes with sitagliptin than with the other medications.

In terms of differences in other effects of the four medications:

- Although the overall incidence of severe hypoglycemia was low, glimepiride was associated with the highest incidence, followed by glargine.

- Participants who received liraglutide and sitagliptin had a mean weight loss of 3.5 kg and 2.0 kg, respectively, at four years, whereas the insulin and glimepiride groups had relatively stable weight.

- As anticipated, participants in the liraglutide group reported the highest frequency of gastrointestinal side effects.

Researchers said their trial was limited by the exclusion of thiazolidinediones and the SGLT2 inhibitor class of glucose-lowering medications. That was “because of safety concerns at the time of planning and the timing of FDA approval, respectively,” they said.

In addition, the selection of single agents within the four medication classes required extrapolation of the current results to other medications within the classes after the non-blinded trial. Study authors also advised that medication adjustments were regularly performed, which is not always the case in the clinical setting.

“The major implication of the current trial is that maintenance of target glycated hemoglobin levels is challenging, even in a clinical trial in which all care is provided free of charge,” the researchers concluded. “The data highlight the need for more effective interventions for long-term control of glycemia in persons with type 2 diabetes.”

Noting that comparative-effectiveness studies usually aren’t performed by industry, the authors suggested, “Our trial presents a clear and objective comparison of the advantages and disadvantages of four commonly used glucose-lowering medications, added to metformin, and these findings should help guide the choice of medications used in the treatment of Type 2 diabetes. These results can form the basis of shared decision-making between providers and patients in selecting the medication to add to metformin.”

“Sitagliptin had less efficacy and durability than the other medications, particularly at higher baseline strata of glycated hemoglobin, and these findings as well as the different adverse-event profiles should be considered along with other clinical benefits and costs in selecting medications used to manage hyperglycemia in persons with type 2 diabetes,” they added.

- Nathan DM, Lachin JM, Balasubramanyam A, Burch HB, et. al. The GRADE Study Research Group. Glycemia Reduction in Type 2 Diabetes – Glycemic Outcomes. N Engl J Med. 2022 Sep 22;387(12):1063-1074. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2200433. PMID: 36129996.