Click To Enlarge: Adjusted Odds of Providers Having Any Video Experience Prior to and During COVID-19

BOSTON — Across specialties, the COVID-19 pandemic has prompted an unprecedented shift toward the use of telemedicine. At the same time, the pandemic has produced a surge in demand for mental health services, as depression and anxiety have dramatically increased.1

Telemental health can improve access to mental healthcare, which is in many ways ideally suited for a telehealth format, given that it typically does not involve a physical examination. A large national analysis of telemental healthcare use within the VA, however, uncovered significant demographic differences in who received video telehealth visits, both prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic.2

The study, which was published in American Psychologist, used national VA records from millions of patients and thousands of providers to better understand the demographic and clinical predictors of phone, video and in-person mental healthcare visits. The researchers looked at appointments that took place both prior to the pandemic (between October 2017—when the VA’s current videoconferencing platform, VA Video Connect, was introduced—and March 10, 2020) and during the pandemic (between March 11, 2020, and July 10, 2020).

Unsurprisingly, researchers found that video telemental health visits shot up during the pandemic. Prior to COVID-19, more than 91% of visits took place in-person, and only 3.5% of patients had completed at least one video visit. After March 11, 2020, nearly a quarter of patients had experience with video visits, and the vast majority of them were first-time users of video telehealth.

Not all patients were equally likely to receive video telemental health services, however. In particular, older and lower-income veterans were less likely to receive video mental healthcare (as opposed to phone or in-person care) during the pandemic.

“These findings are in keeping with the now well-established phenomenon of a ‘digital divide,’ which refers to the gap in the general population between those who have access to and comfort using video-enabled devices, and those who do not,” explained lead researcher Samantha L. Connolly, PhD, investigator at the VA Boston Center for Healthcare Organization and Implementation Research (CHOIR) and assistant professor of psychology at Harvard Medical School. “It is important to note, however, that this finding is not universal; for instance, there have been many provider reports of older adults who have fully embraced video telehealth and enjoy interacting with new technologies.”

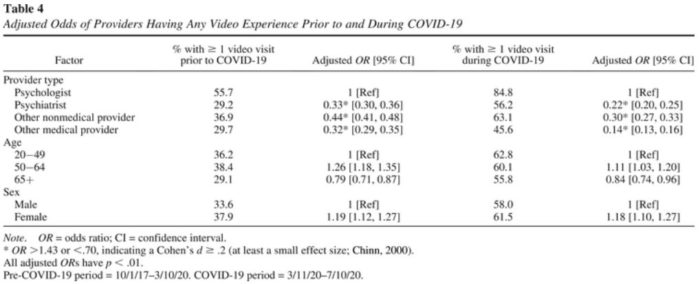

Indeed, the study noted that comfort with video telehealth care is a major factor in getting more providers—who are the gatekeepers to telemental health services—to adopt video technology. Prior to the pandemic, Connolly said, some providers were hesitant to try video telehealth due to concerns regarding privacy, safety and building rapport with patients. However, pandemic-related restrictions on in-person appointments have afforded providers an opportunity to gain video experience despite their hesitations. (The percentage of providers who had completed at least one video visit rose from nearly 38% pre-pandemic to 63% during the pandemic.) As both providers and patients become more familiar with video telehealth, adoption rates may continue to grow.

Increasing Satisfaction

“We know from the literature that, as providers gain more experience with video telehealth, their satisfaction tends to increase. The results reported in our paper are from March to July of 2020, and we’ve already seen substantial increases in rates of video telehealth use since our results were published,” Connolly said.

The VA has also worked to remove structural barriers to telemedicine. The healthcare system has increased veterans’ access to video and internet-enabled tablets and provided education, training and technical support resources to patients and providers. The VA also has set national performance goals to incentivize completion of telehealth visits.

“By increasing access to video-enabled devices and increasing both patient and provider comfort navigating the technology, we can help ensure that all veterans who are interested in and appropriate for video telehealth care are able to receive it,” Connolly pointed out.

In addition, the study found that female veterans were more likely to receive video care than male veterans, even when controlling for age. Connolly noted that, while the team was unable to explore the reason for this gender gap, prior research shows that some women veterans may prefer video visits because their caregiving responsibilities can make leaving home difficult.

The researchers also observed stark differences between types of providers. They found that psychologists were significantly more likely to use video technology compared to psychiatrists, nurse practitioners or social workers, both pre-COVID and during the pandemic. One reason for this might be that psychologists typically have smaller patient caseloads and longer appointment times, which may allow for more time to troubleshoot technical difficulties. If further evidence supports this hypothesis, the authors noted that increasing adoption of video technology may require additional support (for example, having staff conduct test calls with patients ahead of time so that technological issues are worked out prior to the appointment).

The study also suggested that more research is needed to determine differences in the quality and effectiveness of mental health care delivered via phone.

“While there is a large body of literature demonstrating that video care is equivalent to in-person mental health care with regards to effectiveness across a variety of diagnoses and patient populations, we know less about the effectiveness of phone care,” Connolly stated. “We need more data examining the effectiveness of video and phone care in specific clinical scenarios; for instance, a longer psychotherapy appointment versus a shorter medication management check-in. We also need to study the effectiveness of video and phone telehealth in treating patients with more complex presentations, such as those with a diagnosis of schizophrenia or a history of mental health hospitalization.”

Patient satisfaction, which is key to increasing the use of telehealth services, also remains unclear. Connolly advised that scientists don’t yet know how the quality of video and phone telehealth compares to in-person care for patients, and whether it varies based on factors such as diagnosis or appointment type.

- Jia, Haomiao, Guerin, Rebecca J., Barile, John P., et al. National and State Trends in Anxiety and Depression Severity Scores Among Adults During the COVID-19 Pandemic — United States, 2020–2021. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report (MMWR). Published October 8, 2021. DOI: 10.15585/mmwr.mm7040e3.

- Connolly, Samantha L., Stolzmann, Kelly L., Heyworth, Leonie, Sullivan, Jennifer L., et al. Patient and Provider Predictors of Telemental Health Use Prior to and During the COVID-19 Pandemic Within the Department of Veterans Affairs. American Psychologist. Published December 23, 2021. DOI: 10.1037/amp0000895.