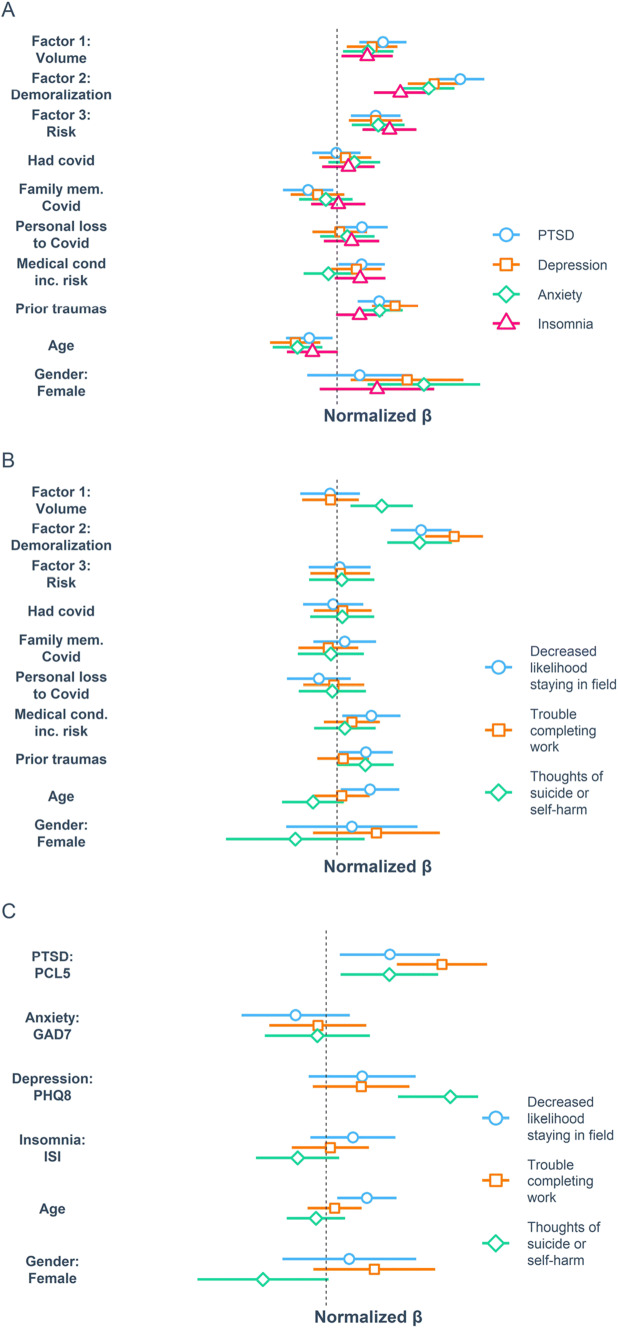

Relationships between different factors of COVID-19-related occupational stressors (CROS factors), psychiatric symptom expression, and functional outcomes. Results of multivariable regression models relating CROS factors and covariates to psychiatric symptom clusters (A) and functional outcome measures along with thoughts of suicide or self-harm (B). C Results of independent multivariable regression models relating symptom clusters as measured by total scores on the PCL5, PHQ9, GAD7, and ISI, along with covariates of age and gender, to functional outcome measures

SEATTLE — As the COVID-19 pandemic exploded and Rebecca Hendrickson, MD, PhD, began hearing reports from friends and colleagues who were in the middle of the first waves in New York and Italy, she found their stories all too familiar.

As a psychiatrist and clinician-researcher at VA Puget Sound Health Care System, Seattle Division, Hendrickson devoted her career to understanding post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in military veterans—particularly the role of nightmares and sleep disruption in its development and persistence. The accounts she was hearing from colleagues in healthcare—periods of prolonged vigilance and exhaustion, punctuated by acute traumatic events, and the development of nightmares and distressed awakenings when they did have time to sleep—were alarmingly similar to what she was used to hearing from veterans.

Concerned about the potential for the development of PTSD and other trauma-related sequelae in these healthcare workers, Hendrickson wanted to understand as rapidly as possible whether this was happening. If it was, she and her colleagues wanted to know what factors either increased or decreased an individual’s risk for chronic symptoms. “Our goal was to identify factors that could be used rapidly to guide prevention and treatment,” she said. Initial results of the project they designed to get answers were reported in December in the Journal of General Internal Medicine.1

The project was based on 17-question online surveys that could be quickly and easily completed by busy healthcare workers and first responders, said Hendrickson. Yet they were detailed enough to help the researchers gain a picture not just of overall levels of distress but also what contextual factors were leading to increased distress, how distress was changing over time and what the consequences of the distress were in terms of occupational functioning and retention, she said. To achieve this, they developed an initial survey that took most people about 20 minutes to complete, and then shorter follow-up surveys at regular intervals for 9 months. The surveys also had a box where respondents could provide their own comments.

Responses from the first 510 participants—who spanned 47 states with a broad distribution across rural and urban populations—were striking, said Hendrickson. “Although we undertook this project explicitly because we were worried about there being high levels of distress in these populations, I did not expect them to be as high as they were,” she told U.S. Medicine.

Across all participants, more than one-third were in the clinical range for PTSD, and nearly three-fourths were in the clinical range for depression and anxiety symptoms. More than 15% of participants reported thoughts of suicide or self-harm in the past two weeks, she said, noting that this includes thoughts of life not being worth living and does not necessarily imply intent to end one’s life.

These numbers were higher for two groups in particular—nurses and EMS. For nurses, more 40% were in the clinical range for PTSD, and more than 80% were in the clinical range for depression. For EMS, more than 80% were in the clinical range for depression symptoms, and nearly one-fourth (24.4%) reported thoughts of suicide or self-harm in the past two weeks.

Responses foreshadowed retention issues among healthcare workers who battled COVID-19. “A substantial proportion of both HCW and FR reported their likelihood of staying in their current field had been somewhat or significantly decreased by their experiences working during the COVID-19 pandemic and that they at least sometimes had difficulty completing work-related tasks,” the authors wrote. “These results are consistent with and build upon findings from previous pandemics and are particularly worrisome given existing concerns about current and future shortages in the health care workforce. The present study suggests healthcare staffing shortages are in and of themselves a COVID-19 stressor, so further shrinking the labor pool could have an exponential negative impact on HCW wellbeing and professional retention.”

Although the study is ongoing, Hendrickson said the first phase offers some important insight. “First, I think it’s really important to remember that healthcare workers and first responders may be professionals who are ‘trained’ to deal with trauma—but we are still human beings, who are affected by what we experience,” she said. “And, it’s important to recognize, because if we do not act to protect our health care workers and first responders, it can result in very high levels of distress and suffering for them as individuals—and, it can also damage our healthcare system, as we risk losing committed and caring individuals from the field.”

The second thing she found striking was “how important someone’s context was,” she said. “One thing that came up a lot was that when people knew there were no better options to care for patients, there was no more PPE to be had in that moment, that everyone was working as hard as they could, they were still affected by the traumatic events they experienced and the personal risks they took—but, it was even harder when they were exposed to the same level of risk or overwhelm when it didn’t seem like it was necessary or it wasn’t clear how decisions were being made.”

Yet the overall message from the study is a hopeful one, she said. “It emphasizes that while we want to minimize the risk and suffering we expose healthcare workers and first responders to; we don’t have to eliminate it entirely for our efforts to provide significant protection and benefit. Instead, workplace practices that facilitate clear and open communication and decision-making, that solicit and respond to the concerns of front-line workers and that minimize unnecessary risk, are likely to have a significant effect in protecting our healthcare workers and health care system.”

Finally, she says the results also highlighted the particular connection of PTSD to negative occupational outcomes and PTSD and depression to thoughts of suicide or self-harm. “These appear to be areas where, if individuals are reporting high levels of symptoms, more proactive support and intervention may be helpful.”

- Hendrickson RC, Slevin RA, Hoerster KD, Chang BP, Sano E, McCall CA, Monty GR, Thomas RG, Raskind MA. The Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Mental Health, Occupational Functioning, and Professional Retention Among Health Care Workers and First Responders. Journal of General Medicine (2021). doi.org/10.1007/s11606-021-07252-z