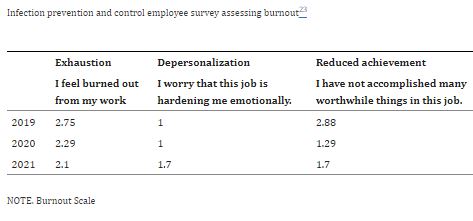

Click to Enlarge: Response Options: 0 = never; 1 = a few times a year or less; 2 = once a month or less; 3 =a few times a month; 4 = once a week; 5 = a few times a week; 6 = every day. Source: American Journal of Infection Control

DALLAS — When the last Ebola epidemic in South Africa threatened to reach pandemic proportions, multidisciplinary staff at VA North Texas Health Care System (VANTHCS) here formed the Serious Infectious Threat Response Initiative (SITRI), developing an all-encompassing algorithm to enable an effective process for communication, safe handling, assessment and care of a patient who might present with Ebola or another emerging pathogen. Staff from multiple disciplines underwent ongoing training on personal protective equipment appropriate for high consequence pathogens.

Five years later, an adaptation of the SITRI helped the system respond to what turned out to be an even larger threat – COVID-19.

The initiative was implemented with continued readiness in mind, said Madhuri Sopirala, MD, MPH, who was director of infection prevention and control at VANTHCS at the time of the program’s implementation “However, when COVID-19 threat loomed, we quickly realized that we were dealing with a pathogen that rendered our prior preparations inadequate and impractical — both nationally and within our institution — and that we needed to adapt.”

The system made COVID-19 protocols early on during the pandemic, Sopirala said. “We created a SITRI phone line that was attended around the clock by our infection prevention experts, who answered staff concerns and questions using hospital approved protocols. The hospital epidemiologist, who is also an infectious disease physician, was available 24/7 to the hospital staff and to the infection preventionists that were scheduled to attend the SITRI phone line.”

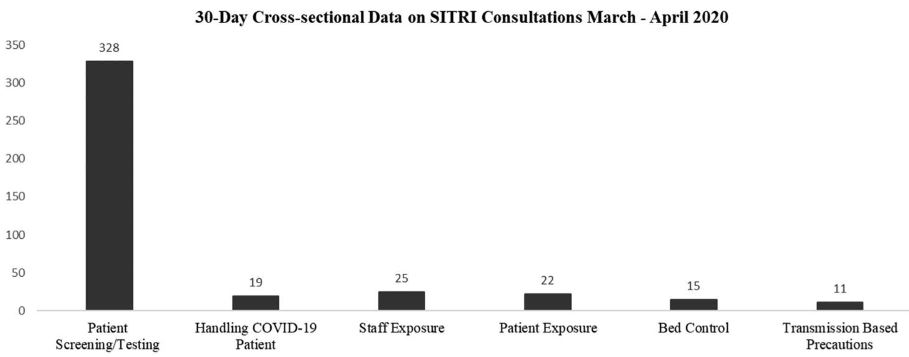

Click to Enlarge: Types of calls received by SITRI during a cross-sectional period of the pandemic from March to April 2020. Source: American Journal of Infection Control

The plan allowed for downtime for infection preventionists following overnight service, she said. The workflow was reorganized, such as having infection preventionists scheduled to cover the SITRI line at any given time also conducting COVID-19 surveillance, data abstraction, exposure management, proper isolation placements and administrative and public health reporting, she said. This allowed infection preventionists not covering SITRI to continue other infection prevention activities such as surveillance for healthcare-acquired infections (HAIs), rounding and feedback to staff on infection prevention practices so as to maintain focus on HAIs during the pandemic.

The primary purpose of SITRI – which Sopirala and VANTHCS colleagues described in American Journal of Infection Control — was to support staff during COVID-19 pandemic. “We assessed correlation between the phone calls received and COVID-19 trends to evaluate how utilization changed as COVID-19 burden changed. We also conducted an electronic employee survey to understand the utility and impact of SITRI. We retrospectively evaluated our HAI incidence before and during the pandemic.”1

The group found a statistically significant correlation between phone calls received and COVID-19 hospital admissions. “Interestingly, our first and highest peak in phone calls was just before our first case of COVID-19 arrived,” Sopirala said. Employee survey results indicated that SITRI was an essential service, she said. “Our HAIs either remained the same or improved during the pandemic.” The group also evaluated infection preventionist burnout using employee survey results before and during the pandemic, she said. These showed that the exhaustion and reduced achievement scales improved during the pandemic, she said, whereas depersonalization — the feeling that a job is hardening someone emotionally– scores got worse. The authors suggested this finding could be associated with compassion fatigue related to the pandemic.

The cost of the initiative was $360,000.

“SITRI helped support staff in a systematic fashion during COVID-19,” Sopirala continued. “Its organized approach helped the institution maintain focus on HAIs during the pandemic through its deliberate attempt to maintain routine prevention efforts by the Infection Prevention and Control program. We were surprised to find the improvement in exhaustion and reduced achievement scores in our [infection preventionist] burn out evaluation. We attribute it to the organized call schedule, separation of COVID-19 and other [infection prevention] tasks.”

Sopirala said VANTHCS could use the same framework in the future if there were to be another pandemic and that infection prevention programs like SITRI with similar framework could be done in any health system with leadership engagement.

Yet, she said, it is difficult to know what to expect with yet another emerging infection. “We learned that COVID-19 took a big toll on HAIs and other non-COVID-19 processes world-wide. With lessons learned and by planning ahead, we could attempt to maintain focus on routine activities to potentially avoid collateral damage. However, we have to understand and remember that our healthcare system supported this program financially by paying overtime as needed for the infection preventionists that supported SITRI. It is extremely important that these types of programs that are designed to improve patient and employee safety are financially supported. That support was key to the implementation and success of the program,” she said.

- Sopirala M, Hartless K, Reid S, Christie-Smith A, et. al. Effect of serious infectious threat response initiative (SITRI) during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic at the Veterans Affairs North Texas Health Care System. Am J Infect Control. 2023 Apr 27. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2023.02.007. Epub ahead of print. PMCID: PMC10132960.