Last year, Sgt. Randy Morris, a combat medic with the 155th Armored Brigade Combat Team, Mississippi Army National Guard, tests a staff member of the Mississippi State Veterans Home in Kosciusko, MI. U.S. Army National Guard photo by Spc. Christopher Shannon II)

LOS ANGELES — The COVID-19 pandemic laid bare the impact of disparities in access to healthcare and ongoing differences in the seriousness accorded to minority patients’ health concerns. It also revealed significant benefits of receiving care through the VA.

Within weeks of the pandemic hitting the U.S., hospital reports and academic studies showed that COVID-10 disproportionately affected Black and Hispanic populations. As data built, the devastation wrought in the American Indian and Native Alaskan population became clear.

Even as the media and healthcare systems publicized the differential impact of the disease on these groups, minority patients continued to face greater difficulty obtaining COVID-19 testing than their white counterparts—except at the VA. In contrast to the national trend, minority veterans were somewhat more likely to receive a COVID test than non-Hispanic white veterans, according to a recent study by Michelle Wong, PhD, and her colleagues at the VA Health Services Research & Development, Center for the Study of Healthcare Innovation, Implementation & Policy, VA Greater Los Angeles Healthcare System, and the VHA Office of Health Equity in Washington.1

“We found that Black and Hispanic veterans were equally, or more likely, to receive a COVID-19 test as White veterans who sought COVID-19-related care,” said Wong and her co-authors. “Black and Hispanic veterans with COVID-19 symptoms or exposure were more likely than White veterans to receive a COVID-19 test at the beginning of the pandemic.”

That finding countered the researchers’ starting hypothesis that “racial/ethnic minority veterans would be less likely to receive a COVID-19 test compared to non-Hispanic White veterans, with greater disparities earlier in the pandemic due to limited awareness of COVID-19 racial/ethnic disparities and restrictions on testing.” It also stands in sharp contrast to the testing patterns seen around the country, particularly early in the pandemic.

When New York led the world in COVID-19 cases in March and April of 2020, researchers discovered that racial composition and socioeconomic status were significant predictors of testing volume and positivity. “More tests were performed in areas with an increasingly white racial composition,” they noted. “Conversely, the highest proportion of positive tests were recorded in nonwhite neighborhoods and in areas defined by a lower SES.”2

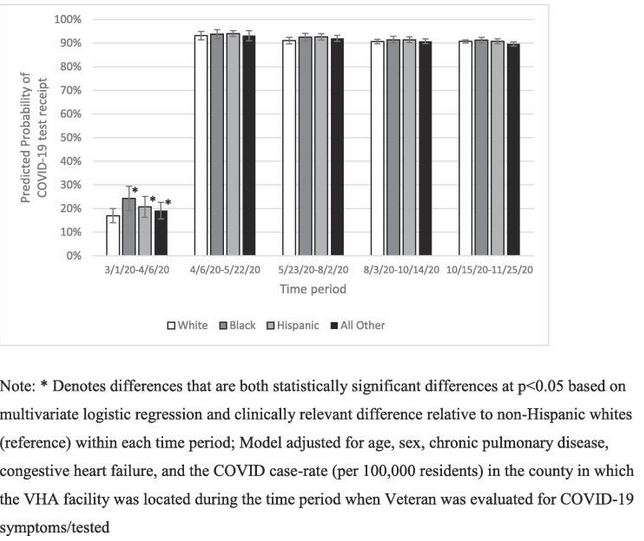

Click to Enlarge: Predicted probability of receiving a COVID-19 test by race/ethnicity and time period, from 3/1/2020–11/25/2020. Note: * Denotes differences that are both statistically significant differences at p < 0.05 based on multivariate logistic regression and clinically relevant difference relative to non-Hispanic whites (reference) within each time period; Model adjusted for age, sex, chronic pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, and the COVID case-rate (per 100,000 residents) in the county in which the VHA facility was located during the time period when Veteran was evaluated for COVID-19 symptoms/tested.

On the other coast, a study of patients who received care for COVID-19 through Sutter Health in California early in the pandemic determined that “a smaller percentage of African Americans (29.9%) were tested for COVID-19 in an ambulatory setting compared to whites (56.0%), Asians (60.0%), and Hispanics (53.8%),” the authors wrote in Health Affairs. “The majority of African Americans were tested in hospitals, either in the ED (37.8%) or as inpatients (32.3%).” Among the reasons suggested by the researchers were lack of access to ambulatory testing in their communities and distrust of the health care system that led patients to delay seeking testing until their symptoms were quite serious.3

VA Testing

The VA researchers analyzed data from 913,806 veterans who sought care for COVID-19 exposure, symptoms, or testing between March 1, 2020, and Nov. 25, 2020 at any VHA facility. Across the full study period, 83% of veterans with COVID-19 exposure or symptoms received a COVID-19 test, but the testing rate varied from a low of just 18% between March 1, 2020, and April 6, 2020, to 90% or more subsequently.

During that early period when tests were difficult to obtain, the predicted probability of being tested for COVID-19 was 17% for white veterans, 24.3% for Black veterans, 20.7% for Hispanic veterans and 19.1% for veterans of other races or ethnicities.

While nearly all veterans with exposure or symptoms of a coronavirus infection after early April received a test, Black veterans and those of other minority races or ethnicities had statistically significantly greater odds of receiving a test than White veterans during the summer of 2020, though that reversed during the fall of 2020. The differences in testing from May through November was not clinically significant.

“Provider biases have led to underdiagnoses and undertreatment of Black and Hispanic patients with other conditions, and reports of challenges in receiving COVID-19 testing,” the authors wrote. “Our findings suggest that within VHA, implicit biases within the healthcare system were unlikely to negatively affect receipt of testing among racial/ethnic minority Veterans who presented with COVID-19 symptoms or exposure.”

The researchers suggested that testing among minority veterans might be more prevalent than seen in other healthcare systems as a result of VHA’s efforts to improve access and reduce health inequities, supporting those goals with rigorous data collection, monitoring of results, screening for risk factors and frequent communication about health disparities.

Given the importance of testing to reducing COVID-19 transmission, the researchers “were encouraged to find that COVID-19 testing was high across all racial/ethnic groups as the pandemic progressed.”

The VA’s example could help model future responses as well, they noted. “Future pandemics will likely also have initial and periodic shortages of test kits; it will be crucial to ensure that racial/ethnic minorities who present with symptoms are able to receive tests.”

- Wong MS, Yuan AH, Haderlein TP, Jones KT, Washington DL. Variations by race/ethnicity and time in COVID-19 testing among Veterans Health Administration users with COVID-19 symptoms or exposure. Prev Med Rep. 2021;24:101503. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101503

- Lieberman-Cribbin W, Tuminello S, Flores RM, Taioli E. Disparities in COVID-19 Testing and Positivity in New York City. Am J Prev Med. 2020;59(3):326-332. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2020.06.005

- Azar KMJ, Shen Z, Romanelli RJ, Lockhart SH, Smits K, Robinson S, Brown S, Pressman AR. Disparities in outcomes among COVID-19 patients in a large health care system in California. Health Affairs. 2020 Jul 1;39(7). https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00598