Restrictions on Family Visits Also Fed Higher Delirium Rates

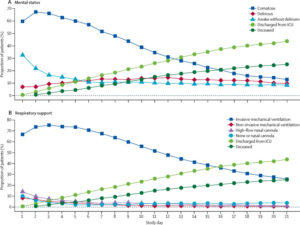

Mental status and respiratory support status in the 21-day study period (n=2088)

(A) Mental status over time. Coma was defined as a day when the patients were unresponsive to verbal stimulation (Richmond Agitation-Sedation Scale score of –4 or –5 or Glasgow Coma Scale score of <8). Patients were considered delirious if they had a positive delirium assessment scale assessment (Confusion Assessment Method for the Intensive Care Unit or the Intensive Care Delirium Screening Checklist) documented. All other patients were considered awake without delirium. Discharge represents discharge from the intensive care unit. (B) Respiratory status over time. ICU=intensive care unit.

NASHVILLE, TN — Whether because of drug shortages or other challenges, many hospital intensive care units apparently reverted to older protocols in treating early COVID-19 patients. That included choice of sedatives which, combined with other factors such as lack of family visitation, increased rates of coma and delirium over what is usually seen with acute respiratory failure, according to a new international study.

Researchers sought to answer the following question: Why did COVID-19 patients admitted to intensive care in the early months of the pandemic have a much higher rate of delirium and coma than is usually identified in acute respiratory failure patients?

The answers included that choice of sedative medications and limits on family visitation increased acute brain dysfunction in those patients. The authors said their study of patients with severe COVID-19 “found that delirium and coma are common and often last for twice the duration in this patient population than that in general ICU patients. This prolonged period of acute brain dysfunction is a potential predictor of worse long-term outcomes of these survivors. The overuse of benzodiazepine sedative infusions and lack of family visitation (either in person or virtual) were associated with more delirium and thus, strategies to modify these approaches might mitigate delirium and any associated sequalae.”

The report in The Lancet Respiratory Medicine, led by researchers at Vanderbilt University Medical Center and including participation from the VA Tennessee Valley Healthcare System, both in Nashville, focused on 2,088 COVID-19 patients admitted before April 28, 2020, to 69 adult intensive care units across 14 countries.1

The authors revealed that about 82% of patients in the observational study were comatose for a median of 10 days, and 55% were delirious for a median of three days. Acute brain dysfunction—whether coma or delirium—lasted for a median of 12 days.

“This is double what is seen in non-COVID ICU patients,” said Vanderbilt’s Brenda Pun, DNP, RN, co-first author on the study with Rafael Badenes MD, PhD, of the University of Valencia in Spain.

Between Jan. 20 and April 28, 2020, 4,530 patients with COVID-19 were admitted to 69 ICUs, of whom 2,088, with a median age of 64, were included in the study cohort. Nearly 70% of the patients were invasively mechanically ventilated on the day of ICU admission, and more than 87% were invasively mechanical ventilated at some point during hospitalization.

The authors noted that infusion with sedatives while on mechanical ventilation was common: 64% of the patients were given benzodiazepines for a median of seven days, and 70.9% were given propofol for a median of seven days.

The study determined that mechanical ventilation, use of restraints and benzodiazepine, opioid and vasopressor infusions, and antipsychotics were each associated with a higher risk of delirium the next day (all p≤0.04). On the other hand, family visitation (in person or virtual) was associated with a lower risk of delirium (p<0.0001).

In addition, researchers reported that, at baseline, older age, higher SAPS II scores, male sex, smoking or alcohol abuse, use of vasopressors on Day 1, and invasive mechanical ventilation on Day 1 were independently associated with fewer days alive and free of delirium and coma (all p<0.01). Slightly more than one-fourth, 28.8%, of the patients died within 28 days of admission, mostly in the ICU.

One problem, according to the authors, was that issues such as shortages of drugs led to a reversion to outmoded critical care practices. Those included deep sedation, widespread use of benzodiazepine infusions, immobilization and isolation from families.

“It is clear in our findings that many ICUs reverted to sedation practices that are not in line with best practice guidelines,” Pun said, “and we’re left to speculate on the causes. Many of the hospitals in our sample reported shortages of ICU providers informed about best practices. There were concerns about sedative shortages, and early reports of COVID-19 suggested that the lung dysfunction seen required unique management techniques including deep sedation. In the process, key preventive measures against acute brain dysfunction went somewhat by the boards.”

Patient Factors

Contributing to those practices were patient factors, such as increased ventilator-patient dyssynchrony, need for higher positive end expiratory pressures, agitation and the decision to prone patients, the authors suggest. They added, “The prolonged use of deep sedation could also be secondary to the increased number of ICU patients observed at our sites, the need to utilize non-ICU-trained staff and inadequate resources with regard to providers, equipment and sedatives.”

Some of those issues might have been unique to the COVID-19 pandemic, which created social isolation resulting from restricted visitation in most hospitals during the pandemic, according to the report. In the study cohort, family visitation occurred on less than 20% of eligible days, but, when visitation was allowed—whether virtual or in-person—the risk of delirium the following day significantly decreased by 27%. “Family presence in the ICU has been associated with decreased anxiety, reduced length of stay and increases in patients’ sense of security, satisfaction and quality of care,” the study noted.

One of the senior authors, Pratik Pandharipande, MD, professor of anesthesiology and surgery at Vanderbilt and part of the VA Anesthesiology Service, explained, “These prolonged periods of acute brain dysfunction are largely avoidable. Our study sounds an alarm: As we enter the second and third waves of COVID-19, ICU teams need above all to return to lighter levels of sedation for these patients, frequent awakening and breathing trials, mobilization and safe in-person or virtual visitation.”

The authors said theirs was the only multisite study to assess critically ill patients with COVID-19 for delirium and coma using validated assessments. It also included the largest cohort of mechanically ventilated patients with COVID-19 published to date. “We found that more than 80% of patients had coma and more than 50% developed delirium,” they added. “These results build on the initial retrospective reports from Wuhan, China, which reported that 40 (45%) of 88 patients hospitalized with severe COVID-19 had nervous system symptoms, with 13 (15%) having impaired consciousness.”

Researchers further emphasized that “prolonged periods of acute brain dysfunction have negative implications for impaired survivorship of patients with COVID-19. Patients with acute brain dysfunction are at high risk of developing ICU-associated dementia and associated post-intensive care syndrome, which affects quality of life and should be avoided by using lighter targeted sedation if possible.”

The study team rejected the concept that most of the brain effects were related to SARS-CoV-2 infection itself, despite early hypotheses to that effect. Instead, the authors posited that “it seems more likely that neurological effects are caused indirectly by factors such as low blood-oxygen levels, coagulopathy, exposure to sedative and analgesic drugs, isolation and immobility.”

The article pointed out that many ICUs were operating in resource-constrained environments, and “despite demonstrated efficacy in previous studies, evidenced-based strategies, such as light sedation techniques, spontaneous awakening and breathing trials, avoiding benzodiazepines, early mobility, and family visitation, all occurred on fewer than 1 in every 3 days among patients with severe COVID-19.”

Researchers recommended avoidance of benzodiazepine sedative infusions, which they said were associated with a 59% higher risk of developing delirium. They urged hospitals to adhere to current sedation guidelines for mechanically ventilated patients, even those with COVID-19.

That means:

- limiting neuromuscular blockade,

- avoidance of continuous infusions of benzodiazepines,

- light levels of sedation,

- frequent awakening and breathing trials, and

- mobilization.

Study authors concluded that those “practices improve short-term outcomes and might also reduce the risk of post-intensive care syndrome, which affects a high proportion of acute respiratory failure survivors.”

- Pun BT, Badenes R, Heras La Calle G, Orun OM, et. Al. COVID-19 Intensive Care International Study Group. Prevalence and risk factors for delirium in critically ill patients with COVID-19 (COVID-D): a multicentre cohort study. Lancet Respir Med. 2021 Jan 8:S2213-2600(20)30552-X. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(20)30552-X. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 33428871; PMCID: PMC7832119.