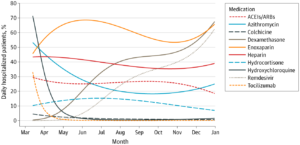

Click to Enlarge: ACEI indicates angiontensin-2 converting enzyme inhibitor; and ARB, angiotensin receptor blocker.

IRVINE, CA — News about medications to treat COVID-19 came fast and furious at the height of the pandemic. Drugs were constantly being touted as showing promise to ameliorate the symptoms—or even cure—the sometimes deadly virus.

But what drugs were actually used in hospitals to combat the novel SARS-CoV-2 virus, which is responsible for more than 118 million cases of COVID-19 and more than 2.6 million deaths worldwide?

To help answer that question, a study in JAMA Network Open reviewed the therapeutic arsenal used in a California hospital system. Researchers from the University of California Irvine School of Pharmacy & Pharmaceutical Sciences and the VA San Diego Clinical Microbiology Laboratory in La Jolla, CA, looked at potential therapeutic options, including dexamethasone, remdesivir, enoxaparin, heparin, colchicine, hydrocortisone, tocilizumab, azithromycin, hydroxychloroquine, and medication classes of angiotensin-2 converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEIs) and angiotensin receptor blockers (ARBs) and then measured daily and overall use percentages for hospitalized patients in 2020.1

Data came from the University of California COVID Research Data Set (UC CORDS), which contains COVID-19 treatment information from all five UC Health medical centers in Davis, Irvine, Los Angeles, San Diego and San Francisco.

The total data set included 22 896 patients with COVID-19; those patients had a mean age of 42.4 and 53.1% were women. Slightly more than 15% ended up being hospitalized. A sample of 6,326 patients included 27.6% non-Hispanic Whites, 37% Hispanics, 6.8% Asians and 5.7% Blacks.

In terms of therapeutics, the authors reported the following:

- Dexamethasone use jumped up from 1.4% (95% CI, 1.4%-1.5%) of COVID-19-diagnosed patients per day on March 31 to 67.5% (95% CI, 62.6%-72.1%) of patients per day on Dec.31.

- Enoxaparin daily usage was 50.4% (95% CI, 45.7%-55.2%) on March 21 and remained above this percentage for the remainder of 2020.

- Remdesivir use shot up more than 12-fold from 4.9% (95% CI, 4.7%-5.1%) on June 1 to 62.5% (95% CI, 56.7%-68.0%) on Dec. 31.

- Azithromycin was used in 45.5% (95% CI, 41.9%-49.1%) of the COVID-19 patients on April 1 but fell by more than half to 20.0% (95% CI, 19.0%-21.1%) by Aug. 1.

- Use of ACEIs/ARBs moderately declined from 27.5% (95% CI, 25.0%-30.2%) on March 31 to 18.5% (95% CI, 16.1%-21.1%) on December 31.

- Heparin overall use was fairly stable over time, at approximately 40%.

- Two other drugs touted as being helpful, tocilizumab and colchicine, were used in 2.4% (95% CI, 2.3%-2.5%) and 2.9% (95% CI, 2.8%-3.0%) cases, respectively, on April 15 but remained below these percentages for the remainder of 2020.

“The home run of this paper is really in the figures built from the UC CORDS database,” said lead author Jonathan Watanabe, PharmD, MS, PhD. “You can clearly see how usage of certain medicines grew or declined over the course of the pandemic and how those movements were tied to evidence-based decisions being made by UC healthcare providers in real time. You can monitor the evolution in how we treat our sickest patients.”

Dramatic Changes

Among the most dramatic changes occurred with hydroxychloroquine, the malaria drug which became politicized during the pandemic. Researchers point out that, in early April 2020, more than 40% of patients up to that point had received hydroxychloroquine. By July, however, fewer than 10% of all patients had received it.

“A small study conducted early in the pandemic favored use of hydroxychloroquine, but later, larger controlled studies found no benefit,” the study team explained.

“There were some studies conducted in the early part of the pandemic that were not particularly well designed and were limited in size that appeared to show hydroxychloroquine to be useful,” Watanabe recounted. “We saw high uptake of the drug early on, but then it just cratered, because as time progressed and more high-quality trials came in, it was shown to be not effective.”

The trend went the opposite way for corticosteroids, partly because the World Health Organization initially recommended against using them for COVID-19. Before May, dexamethasone was used in only 4% of all COVID-19 patients to that point, but the study notes that use accelerated and, by the end of 2020, nearly 40% of all patients received dexamethasone.

“At first glance, a lot of people might say you wouldn’t want to use a corticosteroid that, theoretically, could reduce the immune response in a COVID patient,” according to Watanabe. “But the trials really demonstrated that the knee-jerk mechanism of action-response was not correct in this case: The anti-inflammatory effect of the drug to tame cytokine storms was evidently more important than any blunting of the immune response.”

The shift also was notable for antimicrobials, in general. “This cohort study found that, early in the COVID-19 pandemic, antimicrobials azithromycin and hydroxychloroquine were each used in more than 40% of hospitalized patients. By June, use was below 30% and 5%, respectively,” the authors wrote.

They posited that steady rates of enoxaparin use, which remained above 50% throughout 2020, might have been because the drug can be used for both thrombosis prophylaxis and thrombophilia treatment triggered by COVID-19.

“We tend to put hospitalized patients in general on an anticoagulant to reduce the risk of clots, which can happen because they may be lying in place immobile for long stretches,” Watanabe said. “But then we started to notice thrombophilia in COVID patients, so enoxaparin and heparin both became very important, not just as prophylaxis but as treatments.”

In another case, use of remdesivir grew substantially, at least partly because availability increased over time as trials complete, researchers suggest.

The authors said their review was the first analysis of medication utilization for hospitalized patients with COVID-19 in a large, diverse, statewide health system.

- Watanabe JH, Kwon J, Nan B, Abeles SR, Jia S, Mehta SR. Medication Use Patterns in Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19 in California During the Pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(5):e2110775. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10775