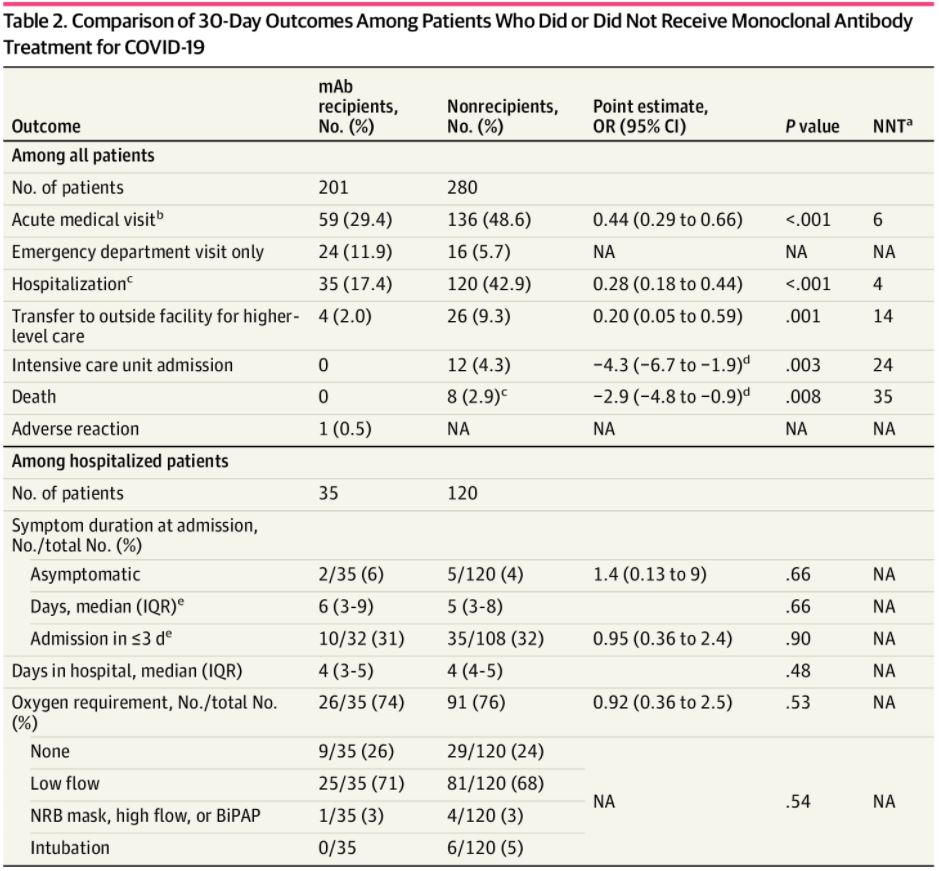

Click to Enlarge: Comparison of 30-Day Outcomes Among Patients Who Did or Did Not Receive Monoclonal Antibody Treatment for COVID-19Abbreviations: BiPAP, bilevel positive airway pressure; IQR, interquartile range; mAb, monoclonal antibody; NA, not applicable; NNT, number needed to treat; NRB, nonrebreather; OR, odds ratio.

a. Number needed to treat to prevent the given medical outcome. Only given if P < .05.

b. COVID-19–related emergency department visit or hospitalization.

c. COVID-19–related hospitalization, including local hospitalizations and transfers.

d. Absolute risk reductions are given as percentages when ORs were not possible.

e. Among patients with known symptom onset dates (32 mAb-treated patients and 108 nontreated patients).

WHITERIVER, AZ — Monoclonal antibody (mAb) therapies were highly effective against COVID-19 in a recent study of Native Americans — a group that has been underrepresented in clinical trials for COVID-19 therapies despite being at greater risk for severe disease.

The study’s 481 participants were patients at the Whiteriver Service Unit (WRSU) on the Fort Apache Indian Reservation in eastern Arizona, who tested positive for COVID-19 between Dec. 1, 2020, and Feb. 3, 2021.1

All participants met the high-risk criteria under the Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) for treatment with bamlanivimab or a combination of casirivimab and imdevimab based on risk factors for severe COVID-19 including body mass index (BMI) and comorbidities such as diabetes, chronic respiratory disease, hypertension or cardiovascular disease. Just under half of the participants, 201, received mAb treatment.

The median time from COVID-19 test collection to mAb treatment was 23 hours, and 182 of the 201 patients (90.5%) received treatment within 72 hours. The median time from symptom onset to treatment was two days, and 113 of 149 symptomatic patients (75.8%) were treated within three days.

Some key findings: Compared with patients who didn’t receive mAb therapies, the mAb-treated patients had a lower proportion of acute medical visits (59 [29.4%] vs. 136 [48.6%]), hospitalizations (35 [17.4%] vs. 120 [42.9%]) and transfers to outside facilities (4 [2%] vs. 26 [9.3%]). Importantly, there were no ICU admissions or deaths among mAb-treated patients compared to 12 and 8, respectively, among non-treated patients, according to the Whiteriver Indian Hospital researchers.

The lower proportion of hospitalizations among the mAb-treated patients observed at WRSU is consistent with previous mAb studies, albeit to a greater degree, according to the study’s authors, who reported the results in a research letter published in JAMA Network Open. “To our knowledge, this study is the first to report mAb use for Native American individuals and is among the few studies to report a significantly lower proportion of deaths among patients receiving mAbs,” they added.

The researchers attributed the magnitude of their findings in part to a higher baseline hospitalization rate. Abiding by EUA criteria meant that eligible WRSU patients, treated and untreated, were at higher risk for severe COVID-19 (e.g., higher BMI and more risk factors) compared with prior studies. Furthermore, Native American individuals experience greater infectious disease mortality, including from COVID-19, which likely increased WRSU hospitalization rates, they wrote.

The success of the WRSU mAb program is also likely attributable to rapid treatment, according to the authors. “The WRSU decreased the time to treatment by integrating contact tracing, clinical outreach, in-house molecular testing, and a unified public health and hospital system that streamlined information exchange,” they wrote. “This approach may not be generalizable but is a model for other centralized health systems.”

The authors recognized several limitations of the study, including the possibility of misclassification due to the study’s retrospective nature. In particular, they said some patients were excluded from mAb treatment solely based on symptom severity, per the EUA. They acknowledged it was possible those patients may have progressed to hospitalization even with mAb treatment, adding it was also possible that earlier mAB intervention may have prevented the progression.

“Given the magnitude of our findings, we believe they are unlikely to be entirely the result of misclassification,” the authors concluded. “Therefore, we assert that the success of the WRSU mAb program suggests that these treatments can be used to great effect in rural, relatively resource-limited settings.”

Information from public health officials underscored the importance of effective treatment—as well as mass vaccination—for American Indian populations.

At the end of last year, the national Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that, among American Indian/Alaska Natives, patients who died from COVID-19 were younger than were white patients: 35.1% of AI/AN COVID-19-associated deaths were among persons aged younger than 60, compared with 6.3% of deaths among whites.

In the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, CDC pointed out that the age-adjusted AI/AN COVID-19 mortality rate (55.8 deaths per 100,000) was 1.8 (95% CI = 1.7-2.0) times that among white people (30.3 deaths per 100,000). The statistics were based on reporting from 14 states where about half of the AI/AN population lives.2

At the time, for both AI/AN and whites, mortality was higher among men (66.4 and 36.1 per 100,000, respectively) than among women (46.8 and 25.4 per 100,000, respectively). Public health officials noted that, among both AI/AN and white persons, COVID-19 mortality rates increased with age, with the highest age-specific mortality rate among persons aged ≥80 years (488.3 and 520.1 per 100,000, respectively).

“Mortality rates among AI/AN persons were higher than those among White persons in all age groups except the oldest age group,” the CDC authors wrote. “The largest differences were among persons in the three age groups encompassing 20-49 years. Among persons aged 20-29 years, 30-39 years and 40-49 years, the COVID-19 mortality rates among AI/AN persons were 10.5, 11.6 and 8.2 times those among White persons, respectively.”

- Close RM, Jones TS, Jentoft C, McAuley JB. Outcome Comparison of High-Risk Native American Patients Who Did or Did Not Receive Monoclonal Antibody Treatment for COVID-19. JAMA Netw Open. 2021; 4(9):e2125866. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.25866

- Arrazola J, Masiello MM, Joshi S, et al. COVID-19 Mortality Among American Indian and Alaska Native Persons — 14 States, January–June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1853–1856. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6949a3external icon.