WASHINGTON — A recent Government Accountability Office report calls into question VA’s belief that upcoming IT modernization projects will fix long-standing problems in its medical supply chain.

Delays have already plagued several of the projects, and the scope of the work suggests more delays are possible. Legislators also are questioning whether IT fixes are enough and whether there might be more systemic problems in VA’s structure that are leading to difficulties getting the right equipment to medical centers when they need it.

At a House Veterans’ Affairs Oversight Subcommittee hearing last month, Rep. Chris Pappas (D-NH) said, “VA’s supply chain initiatives create a dizzying array of overlapping efforts and confusion.”

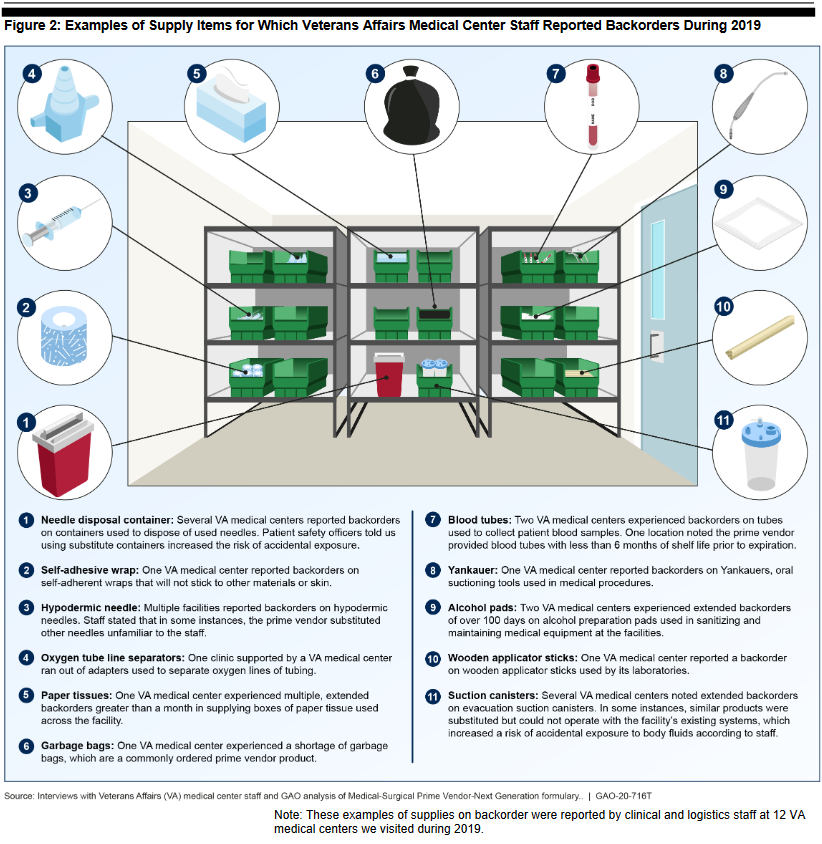

VA’s acquisition problems had been well documented long before the pandemic began, with GAO adding VA’s acquisitions process to its high-risk list in 2019. That was mostly due to medical supply chain problems. When GAO visited 12 VA medical centers in 2019, every facility reported experiencing challenges with back orders of needed supplies using the current Medical Supply Prime Vendor (MSPV) program. Back-ordered items included commonly used material such as alcohol pads, hypodermic needles, paper tissues and garbage bags.

When a prime vendor lacked the available inventory to fulfill an order, some VAMCs chose to wait for the backorder to resolve, resulting in delivery delays that then led to delayed or cancelled procedures. In some cases, VAMC staff were forced to find workarounds, such as using government purchase cards to meet facility needs.

Implementation of the next generation of the prime vendor system, MSPV 2.0, is one of the modernization projects VA has said it hopes will help shore up its supply chain. The MSPV system was adopted by VA in 1993 as a “just in time” model to replace the previous supply depot system. The model has proven vulnerable, however, to outside disruptions in the supply chain.

According to VA, MSPV 2.0 will address supply shortfalls by expanding the number of items on the formulary and directing prime vendors to keep a 30-day supply of regularly ordered items in stock to cut down on back orders in addition to other measures.

Contracts for VA’s current MSPV program were scheduled to run out in March 2020. VA had intended to begin MSPV 2.0 in April 2020 to ensure uninterrupted service. The 2.0 prime vendor procurement was subject to multiple bid protests that delayed implementation until at least January 2021, however. Consequently, VA has needed to resort to short-term bridge contracts with its current prime vendors.

“It will take some time to recognize the improvements of MSPV 2.0. Furthermore, it will not address all the challenges,” Shelby Oakley, GAO’s director of contracting and national security acquisitions, told the subcommittee.

VA is also piloting another MSPV program—one currently in use by the Defense Logistics Agency (DLA)—at the James A. Lovell Federal Health Care Center in Chicago. The goal is to see if the DLA program is more efficient and effective than its own 2.0 program and should be rolled out to all VA facilities.

“This pilot has been delayed by almost a year,” Oakley explained. “And our work has found that VA lacks a comprehensive methodology to measure the pilot’s success and scalability across its medical centers.”

Going hand in hand with the revamping of the MSPV program is VA’s transition to the DoD’s inventory management system—Defense Medical Logistics Standard Support (DMLSS). DMLSS serves as the primary ordering system for DLA’s MSPV program and supports DLA’s inventory management.

A switch to DMLSS would result in the ability for VA to track supply needs across the entire enterprise, providing much-needed transparency and understanding of the needs of each facility.

As with MSPV, the DMLSS switch has experienced delays. VA had planned to implement DMLSS at three VA medical centers in 2019. Due to technology integration issues, this has been delayed by over a year. VA began the switch to DMLSS at its first site—the James A. Lovell VAMC—in August. VA officials said they expected the system to be fully up and running at Lovell by the end of September.

Seven Years for Full Rollout

A full rollout of DMLSS across VA is expected to take as long as seven years. This timeframe has been of particular concern to legislators. The inability for VA to understand what facilities need what supplies was a key difficulty the agency faced in the early days of the pandemic. While VA created some patchwork solutions, the department continues to rely on facility staff manually inputting supply updates, resulting in increased workload for overstretched staff and unnecessary delays for VA management trying to get a handle on national supply needs.

Previously, VA officials have said they are exploring ways to shorten that seven-year timeframe. That might be easier said than done, explained Deborah Kramer, acting assistant under secretary of health and support services.

According to Kramer, the money and time needed to keep up the old systems while they are in the midst of being replaced is a resource drain. She also admitted that replacement of the electronic health record system (EHRS) remains VA’s biggest IT priority.

“Replacing the financial management and acquisitions system, the supply chain and the EHRS—that will get rid of the biggest share of our legacy systems, which frankly consume the greatest amount of our IT sustainment budget,” Kramer told legislators. “Just keeping those old systems operating. That’s what slowed us down. We’re investing a great deal in keeping the old systems up, and that makes the finances not available.”

Asked if VA’s plan, which juggles the MSPV, DMLSS and EHRS projects simultaneously, is reasonable, Oakley was not optimistic.

“If you look at VA’s past performance in making major changes like this at VA, they’ve all been challenged and delayed and stopped and restarted over and over again,” she said. “The three significant systems Ms. Kramer mentioned are happening at the same time, and each on their own bring significant risks and are all dependent on each other.”

Questions were also raised as to whether IT modernization would be enough to fix VA’s supply chain issues.

Rep. Jack Bergman (R-MI), cited the Commission on Care’s report released in 2016. The report looked at what VA needed to accomplish over the next two decades to deliver the best care to veterans.

“VHA cannot modernize its supply chain management and create cost efficiencies because it is encumbered with confusing organizational structures, no expert leadership, antiquated IT systems that inhibit automation, bureaucratic purchasing requirements and procedures, and an ineffective approach to talent management,” he quoted.

To the VA officials present at the hearing, he asked, “You have a path in mind to modernize the IT system, but what are you doing to reform the organizational structure and bureaucracy?”

Kramer told Bergman that the bureaucratic reorganization has already occurred. “We’re now aligned to support the field. We have subject matter experts in key leadership positions. Andrew Centineo, his new deputy, myself—we’re all former Army medical logisticians. We did this under combat conditions. We’re bringing that level of expertise to VA to help us make progress much faster.”