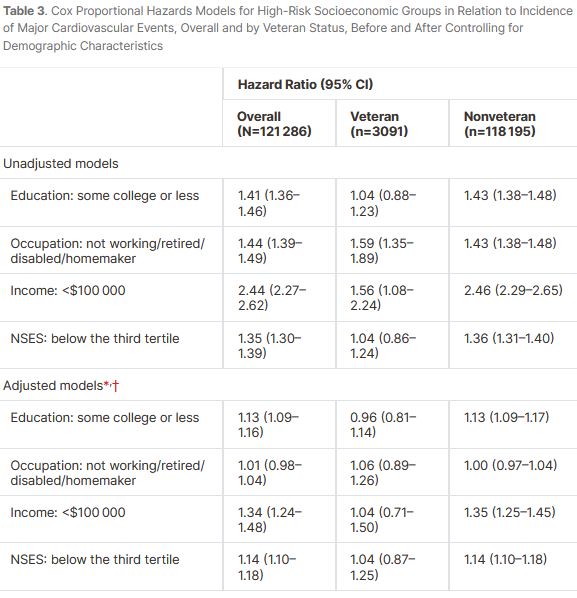

Click to Enlarge: NSES indicates neighborhood socioeconomic status; and WHI, Women’s Health Initiative.

* Adjusted for WHI component (Clinical Trials, Observational Study), region of residence (Midwest, Northeast, South, West), age (50–54, 55–59, 60–64, 65–69, 70–74, 75–79 years), race (American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islanders, Black, White, more than one race, unknown/not reported), ethnicity (Hispanic, non‐Hispanic, unknown/not reported), and marital status (married/partnered, single, divorced, widowed).

† Interaction terms of occupation × veteran status (P=0.45), and veteran status×NSES (P=0.08) in Cox regression models adjusted for WHI component, region, age (categorical), race, ethnicity, marital status, the socioeconomic characteristic, and veteran status were not statistically significant. However, the interaction term of education × veteran status (P=0.02) and household income × veteran status (P=0.03) in a Cox regression model adjusted for WHI component, region, age (categorical), race, ethnicity, marital status, household income, and veteran status were statistically significant. Source: Journal of the American Heart Association

WASHINGTON, DC — In contrast to the civilian population, certain indicators of socioeconomic status, such as education, occupation, household income and neighborhood socioeconomic status, aren’t significantly linked to major cardiovascular disease events in postmenopausal women veterans, according to a recent study.

The prospective cohort study published in the Journal of the American Heart Association examined the association of selected indicators of socioeconomic status (education, occupation, household income and neighborhood socioeconomic status) with risk of major cardiovascular disease events in veteran and nonveteran postmenopausal women. The study authors are affiliated with the VA in Washington, D.C.1

Cardiovascular disease is a leading cause of death for women in the United States, and, due to accelerated aging and biopsychosocial mechanisms, veterans are at potentially higher risk than nonveterans. Few studies have explored how socioeconomic status might influence cardiovascular disease risk while comparing veteran and nonveteran women in the United States, according to what Hind A. Baydoun, PhD, MPH, a health science specialist at the National Center on Homelessness Among Veterans (NCHAV), told U.S. Medicine.

This research gap is important for several reasons. Studies have shown women face disparities in cardiovascular outcomes, including delayed care for heart conditions, higher hospital mortality rates after heart attacks and less consistent care following strokes. In addition, the number of women joining the U.S. military is growing, with female veterans expected to exceed 2 million in the coming decades. Prior research also suggests that military service might contribute to an increased risk of cardiovascular disease. Lastly, socioeconomic status—which includes education, income, occupation and neighborhood factors—can impact cardiovascular risk through stress, inflammation and other mechanisms, Baydon explained.

In this study, the researchers followed 121,286 study‐eligible Women’s Health Initiative participants, which included 3,091 veterans and 118,195 nonveterans, for an average of 17 years. During this time, 16,108 major cardiovascular disease events were documented. Participants were 50 to 79 years old at baseline, and they were recruited between 1993 and 1998 at 40 geographically diverse clinical centers (24 states and the District of Columbia) in the U.S.

Data collection included self‐administered questionnaires, in‐person/telephone interviews and clinical measurements. Information was available on veteran status, individual‐ and neighborhood‐level socioeconomic characteristics, as well as demographic, lifestyle and health characteristics.

Using statistical analysis, the investigators estimated the effects of socioeconomic status on major cardiovascular disease events through smoking, body mass index, comorbidities, cardiometabolic risk factors and self‐rated health. They controlled for Women’s Health Initiative component, region, age, race, ethnicity, marital status and healthcare provider access.

“The study found that the selected indicators of socioeconomic status (education, occupation, household income and neighborhood socioeconomic status) were not significantly related to major cardiovascular disease events among veteran postmenopausal women,” Baydoun said. “However, among nonveteran postmenopausal women, the following were associated with a greater risk of major cardiovascular disease events: having some college education or less, household income under $100,000 or a neighborhood socioeconomic status in the lower two-thirds.”

The findings suggest that for veterans, socioeconomic factors were linked to major cardiovascular events mainly through body mass index, comorbidities, cardiometabolic risks and self-rated health. For nonveterans, the pathways were more complex, involving education, income and neighborhood socioeconomic status. Also, smoking played a role in major cardiovascular disease events only among nonveterans, Baydoun pointed out.

Overall, this study found a stronger connection between socioeconomic status and major cardiovascular disease events in nonveteran postmenopausal women compared to veterans, with more complex pathways linking socioeconomic factors and cardiovascular events in nonveterans, she suggested.

Tailored Strategies

“These findings can help guide healthcare professionals in tailoring prevention strategies to address the specific needs of postmenopausal women based on veteran status,” Baydoun said. “Healthcare professionals should consider the unique challenges veteran women face. Future interventions should address these barriers and account for the limited impact socioeconomic factors may have on improving health outcomes for veteran women. For all postmenopausal women, veteran, and nonveterans alike, focusing on modifiable risk factors—like managing weight, addressing health conditions and improving lifestyle habits—can help reduce the risk of major cardiovascular events.”

This study is among the first to highlight the importance of considering the unique barriers faced by veteran women as a marginalized group, when examining the relationship between socioeconomic status and cardiovascular disease outcomes, according to study authors.

Other studies, contrary to this study’s results, have found cardiovascular disease risk factors to be more prevalent among female veterans than civilian counterparts and that veterans had higher prevalence rates of obesity, obesity‐related chronic conditions (e.g., hypertension, diabetes and hyperlipidemia) and smoking. This study found that veteran postmenopausal women were 55% more likely to experience a major cardiovascular disease event compared to nonveteran counterparts. However, the relationship was confounded by demographic, socioeconomic, lifestyle and health characteristics, so the study controlled for these factors, according to the researchers.

It’s possible that age was the main factor for differences in major cardiovascular disease risk between veteran and nonveteran women in the Women’s Health Initiative, the authors suggested. In this study, nearly 50% of veteran women were 70 years and older, compared with only 22% of nonveteran women. The researchers reported the age‐adjusted hazard ratio for the relationship between veteran status and major cardiovascular disease risk was 1.04 (95% CI, 0.96-1.14).

The researchers also noted that veterans may have unique protective factors, such as access to healthcare and case management supports through the VA.

- Beydoun HA, Beydoun MA, Kinney RL, Liu S, et. Al. Pathways From Socioeconomic Factors to Major Cardiovascular Events Among Postmenopausal Veteran and Nonveteran Women: Findings From the Women’s Health Initiative. J Am Heart Assoc. 2024 Dec 17;13(24):e037253. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.124.037253. Epub 2024 Dec 14. PMID: 39673348.