Researchers Call Their Findings ‘Alarming’

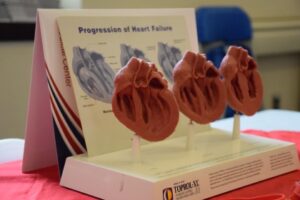

A display shows the progression of heart failure at a clinic at Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, MD. A new study suggested that care disparities continue to exist for patients treated by the Military Health System. Photo by Megan Garcia, WRNMMC Public Affairs

BETHESDA, MD — Heart failure affects an estimated 6.2 million adults in the United States and is associated with disability, diminished quality of life and a 5-year mortality of 50%.

Although heart failure occurs across all demographics, lower socioeconomic status and Black race are associated with a greater risk. This association has largely been attributed to those groups’ lack of access to quality medical care. A new study of enrollees in the MHS—which offers universal coverage to active duty, reserve component and retired U.S. military personnel and their dependents—raised questions about those assumptions.

The report in the American Journal of Medicine indicated that disparities in heart failure related to race and income exist despite equal access to care.1

As part of their ongoing work to better understand health disparities, researchers at the Uniformed Services University of the Health Science and three NIH Institutes—the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute, National Institute on Minority Health and Health Disparities and National Human Genome Research Institute—conducted a cross-sectional observational study of adult beneficiaries aged 18 to 64 years of the MHS for fiscal year 2018-2019. The study team calculated prevalence of preclinical (Stages A/B) or clinical (Stages C/D) heart failure stages as defined by professional guidelines. They analyzed results by age, race and socioeconomic status, using military rank as a proxy.

Among about 5.4 million MHS beneficiaries aged 18 to 64 years, prevalence of preclinical and clinical heart failure was 18.1% and 2.5% respectively, the authors reported. Patients with preclinical heart failure were middle-aged with similar proportions of men and women, while those with heart failure were older and mainly men. After multivariable adjustment, Black race and lower socioeconomic status were significantly associated with large increases in the prevalence of all stages of heart failure.

“It was previously known that Black Americans are more likely to develop clinical heart failure than white Americans, but the explanation is unclear,” said Tracey Perez Koehlmoos, PhD, MHA, director of Uniformed Services University’s Center for Health Services Research. “It also was previously known that lower socioeconomic status is associated with more heart failure, as well as a host of other negative health outcomes.” One explanation for this latter finding, she said, was that patients with lower socioeconomic status had less access to medical care.

Varied Socioeconomic Status in Military

“In this study, we were able to eliminate the issue of reduced access to medical care as a variable and control for socioeconomic status,” Koehlmoos said. “Because senior officers are paid more than junior enlisted members, a gradient of socioeconomic status is still present in the military,” she explained.

“As anticipated, senior officers who enjoy higher socioeconomic status had significantly less heart failure than the enlisted cohort,” she continued. “However, at every level of socioeconomic status, Black members had significantly greater prevalence of heart failure than white members, despite receiving the same salaries and benefits. Therefore, elimination of both the barrier to medical care and differences in pay failed to eliminate the excess prevalence of heart failure among Black military members. Black senior officers were 2.4 times more likely than white senior officers to have clinical heart failure despite similar pay, status, and access to medical care.”

Many of the group’s other studies in the MHS show a mitigation or amelioration of these disparities seen in other healthcare systems and settings, said Koehlmoos, who added, “So the presence, particularly in the pre-clinical, young population was considered alarming.”

Koehlmoos said for the U.S. and the MHS, this study is really a first look at heart failure across the different stages in that younger, working-age population with no barriers to insurance. Most of the studies are on samples, but this was an entire population, she said.

“People often think of the Military Health System as serving active duty only—so somehow inherently different from the general U.S. population, but really, active-duty servicemembers constitute only 18% of our 9.6 million beneficiaries. Our data have demonstrated great generalizability to the U.S. population,” Koehlmoos pointed out.

Identifying the residual drivers of this heart failure disparity is beyond the reach of this study, Koehlmoos said, but she believes these findings will help propel future research.

The study also sends the message to physicians that “we need to be watching out for our younger population—who are Black and of junior rank,” she said. “They may present as being ‘fine’ or report feeling ‘fine’ and not be taking this real risk of heart failure and their role in prevention as seriously,” she said. “Or we may not be providing those messages in a way that says, ‘You can change your future, but you have to act now.’ That heart failure is not ‘an old man’s’ disease, but something that develops over a lifetime and can be slowed and prevented.”

- Roger VL, Banaag A, Korona-Bailey J, Wiley TMP, Turner CE, Haigney MC, Koehlmoos TP. Prevalence of Heart Failure Stages in a Universal Healthcare System The Military Health System Experience. Am J Med. 2023 Jul 20:S0002-9343(23)00459-X. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2023.07.007. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 37481019.