U.S. Army Combat Engineers assigned to the 104th Brigade Engineer Battalion, 44th Infantry Brigade Combat team, New Jersey Army National Guard, conduct obstacle breaching and demolition operations at Joint Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst, NJ, last month. New Jersey, March 2, 2025. Researchers said servicemembers are tactical athletes called to perform under high stress, temperature extremes, and in austere locations. U.S. Army National Guard photo by Sgt. Seth Cohen

BETHESDA, MD — Sudden cardiac arrest is a silent and often fatal event that strikes without warning, even among those in peak physical condition. In the civilian world, survival rates for out-of-hospital cardiac arrest are alarmingly low.

A new study sheds light, however, on how the U.S. military’s rigorous emergency response protocols and commitment to the philosophy of “leave no one behind” may be saving lives at a much higher rate.

The military environment presents unique cardiovascular challenges, explained Alaric Franzos, MD, associate professor, medicine and cardiology, at Uniformed Services University and first author of the new study published in the American Journal of Medicine.1

“Our military members are tactical athletes called to perform under high stress, temperature extremes and in austere locations,” he said. Unlike competitive athletes who typically have medical personnel on standby, servicemembers often operate in environments where immediate medical assistance may be limited or entirely unavailable, he said. This reality makes it crucial for commanders and individual soldiers alike to have confidence in their cardiovascular resilience.

In the U.S. military, rigorous physical fitness tests (PFTs) are used to assess readiness, but they also introduce risk. “Since physical fitness is one component used for promotion, tactical athletes may go to extremes to make weight and push through warning symptoms to achieve their goal time,” Franzos told U.S. Medicine. This combination of intense exertion and potential underlying heart conditions might contribute to a higher risk of fatal cardiac events.

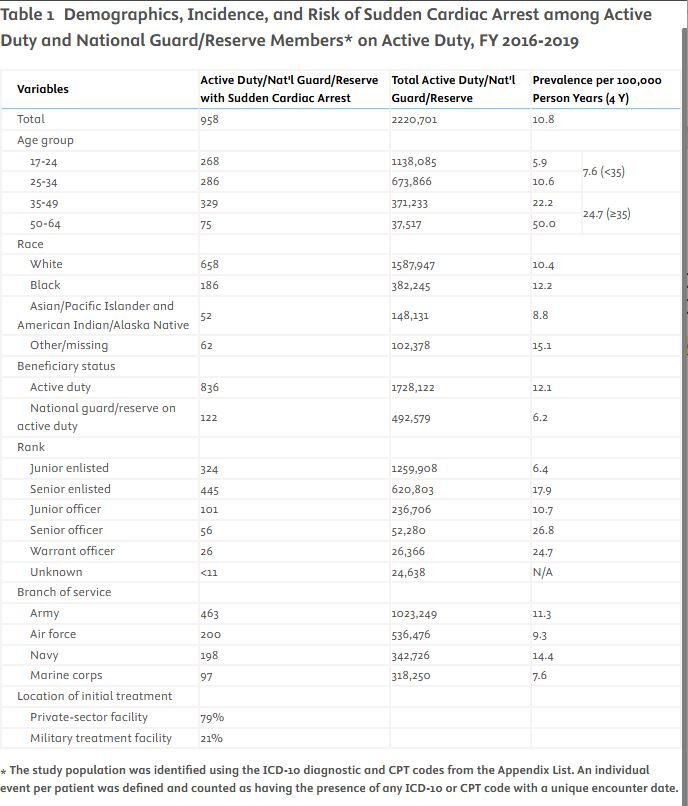

The study, which analyzed data from the Military Health System Data Repository between 2016 and 2019, found that the incidence of sudden cardiac arrest among active-duty military personnel was 10.8 per 100,000 person-years—a significant rate, given the expected fitness levels of servicemembers. However, what stands out is the survival rate. Among servicemembers who were transported to a hospital, 30-day survival rates were remarkably high: 73% for those under age 35 and 76% for those age 35-64.1

These numbers starkly contrast with the civilian population, where survival from out-of-hospital cardiac arrest is often less than 10%. “We were surprised by the very high survival rate,” Franzos admitted. “If we assume that 39% of sudden cardiac arrest victims are not transported [a figure derived from the literature], we estimate that the overall survival rate is closer to 48%.” Even at this adjusted rate, military personnel are surviving cardiac arrests at around 4 times the rate of civilians.

Click to Enlarge: Demographics, Incidence, and Risk of Sudden Cardiac Arrest among Active Duty and National Guard/Reserve Members* on Active Duty, FY 2016-2019 Source: American Journal Of Medicine

One likely factor contributing to the higher survival rate in the military is the emphasis on immediate response. “The rate of receiving bystander CPR before EMS arrived was 85% on military bases compared to 63% off-base,” the authors noted. Additionally, the rate of automated external defibrillator (AED) use before EMS arrival was 55% on bases vs. just 28% in civilian settings.

These interventions are critical. Research has shown that every minute without defibrillation reduces the chance of survival by approximately 10%. “CPR can provide a temporizing measure until a defibrillator arrives. But CPR is not the definitive intervention,” Franzos said.

“I think that the kind of bottom line here is that, in the military community, there is attention to access to AEDs as well as a significant amount of people who are trained in these basic life support life-saving methods,” said Lydia D. Hellwig, PhD, a certified genetic counselor, assistant professor of pediatrics at the Uniformed Services University and study co-author. “And so I think is something that we definitely would hypothesize that could potentially explain some of those differences between the survival rates in the military versus the civilian population.”

Despite the military’s proficiency in responding to sudden cardiac arrest, the study’s authors emphasize that more must be done on the prevention front. Currently, military screening for cardiovascular health relies on a focused history and physical examination, but it does not include routine electrocardiograms (ECGs). Franzos doesn’t know if including ECGs would be beneficial, but he hopes to find out through a pilot program directed by Congress that is looking at resuming ECG screening for military medical assessments at a recruit site.

Another piece regarding prevention involves efforts to better understand the cause of sudden cardiac arrest—regardless of whether victims survive—using genetic and other forms testing. In 50% of SCA cases, the cause is never known. By better understanding the cause, researchers hope not only to find answers to why it happens but how to prevent it in surviving family members and others, Franzos said.

Additionally, efforts are underway to improve AED accessibility. “We strongly recommend having AEDs readily available at graded, timed, or high-risk physical fitness events,” Franzos stressed.

Hellwig stressed that more work is needed to better understand the risk factors for sudden cardiac arrest and sudden cardiac death and implementation of preventive measures. “It’s something that we hope to be working on into the future as well is our continued efforts to try to better understand and prevent these events,” she said.

- Franzos MA, Hellwig LD, Thompson A, Wu H, et al. No One Left Behind: Incidence of Sudden Cardiac Arrest and Thirty-Day Survival in Military Members. Am J Med. 2025 Feb 18:S0002-9343(25)00091-9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2025.02.003. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 39978666.