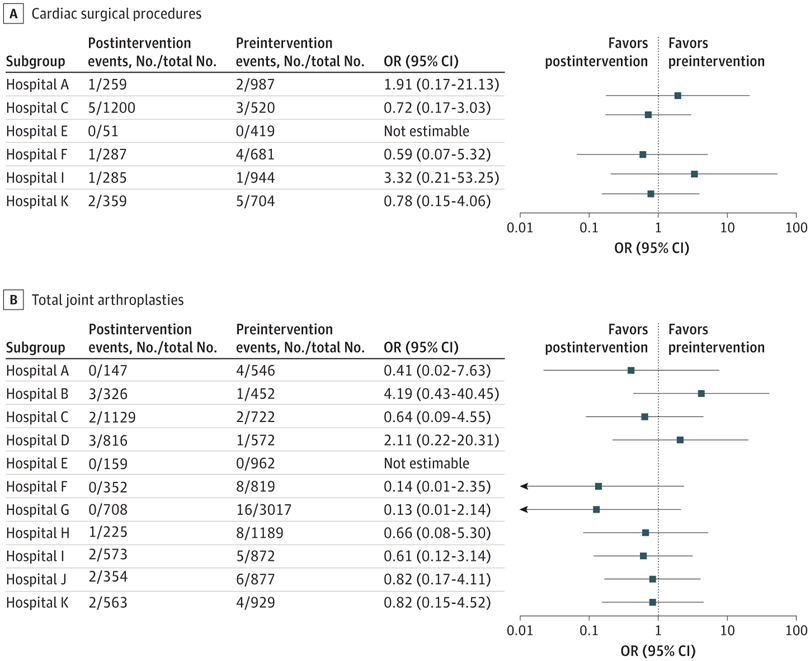

Click to Enlarge: Number of Surgical Procedures and Surgical Site Infections During Preintervention and Post-intervention Periods, OR indicates odds ratio. Source: JAMA Network Open

IOWA CITY, IA — Surgical site infections (SSIs) are associated with significant morbidity and mortality, prolonged length of hospital stay and readmission. In a new VA study, the implementation of an SSI prevention bundle with facility-level discretion on its components was associated with a decreased risk of these dangerous infections.

The most common etiology of adult SSIs and, specifically, the most common pathogen cause of SSIs among orthopedic and cardiac surgery patients is Staphylococcus aureus, said Hiroyuki Suzuki, MD, MSCI, infectious diseases physician and hospital epidemiologist at Iowa City, IA, VAMC. “For that reason, it is a good target for SSI prevention efforts.”

In a previous study of 20 non-VA hospitals, researchers found that implementation of an SSI prevention bundle targeted for S. aureus SSI decreased the rate of deep incisional or organ/space S. aureus SSI by 42% among patients undergoing cardiac or orthopedic surgery.1

“However, it is well known that interventions are not one-size-fits-all and may need to be modified to address facility-level factors,” said Suzuki. To assess the real-world effectiveness of an SSI prevention bundle, the researchers “conducted a quasi-experimental before-and-after study of all patients who underwent cardiac surgeries or total joint arthroplasty—that is hip and knee replacement—at 11 VA medical centers,” he added.

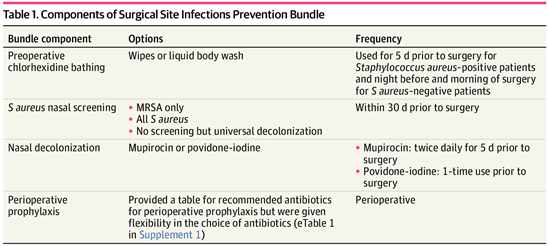

The bundle, which was implemented at the 11 hospitals, included five components:

- preoperative nasal testing for the bacteria called S. aureus within 30 days of the operation;

- preoperative use of a nasal ointment called mupirocin twice daily for 5 days to get rid of the bacteria among people who tested positive for S. aureus;

- bathing with the antiseptic chlorhexidine for 5 days prior to surgery for those with S. aureus in their noses, and 2 days for those who tested negative for S. aureus;

- perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis with the antibiotic cefazolin unless the patient was known to have Methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) bacteria in their nose; and

- perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis with both vancomycin and cefazolin antibiotics for patients known to have MRSA in their noses. 2

Flexibility Allowed

Click to Enlarge: Abbreviation: MRSA, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus Source: JAMA Network Open

Hospitals were allowed flexibility in how to implement specific components of the bundled intervention, however, said Suzuki, who explained. “For example, they could choose to screen MRSA only or both Methicillin-susceptible S. aureus and MRSA. Similarly, hospitals could choose the way of chlorhexidine bathing—wipes or liquid—or replace mupirocin with intranasal povidone-iodine.”

The study, which was published in JAMA Network Open, included 23,005 surgical procedures—6,696 cardiac surgeries and 15,949 orthopedic surgeries. There was not a statistically significant association between the intervention and deep or organ/space SSI among the cardiac surgeries—15/4255 (0.35%) deep or organ/space SSIs occurred before the intervention and 10/2441 (0.41%) SSIs occurred during the intervention period. Suzuki attributed this to “multiple barriers to getting the bundle to cardiac surgery patients, such as the short time frame between determining that a patient needs open-heart surgery and the surgery.”

There was, however, a statistically significant association between the intervention and decreased deep or organ/space S aureus SSI among patients undergoing total joint arthroplasties, Suzuki said. For orthopedic surgeries, 55/10957 (0.50%) deep or organ/space SSI occurred before intervention and 15/5352 (0.28%) SSI occurred in intervention period. 0.31-0.98). The association was not observed with the interrupted time-series analysis considering the time from intervention (adjusted incidence rate ratio 0.88. 95% CI 0.32-2.39).

“It was disappointing we did not see a significant association using interrupted time-series analysis,” Suzuki said. “We thought we were underpowered to show the difference due to the rarity of the deep or organ space SSI in each time point when interrupted time-series analysis was used.”

Suzuki said the results suggest that an S. aureus SSI prevention bundle for patients undergoing total joint arthroplasties might decrease S. aureus deep or organ/space SSI in the real-world setting. “According to our estimate, about 500 patients will need to get the bundle to prevent one deep or organ space SSI after total joint arthroplasties,” he said. “Considering the large number of patients needing total joint arthroplasties and significant burden when SSI occurs, there would be a significant benefit of implementing S. aureus SSI prevention bundle.”

- Schweizer ML, Chiang HY, Septimus E, Moody J, Braun B, Hafner J, Ward MA, Hickok J, Perencevich EN, Diekema DJ, Richards CL, Cavanaugh JE, Perlin JB, Herwaldt LA. Association of a bundled intervention with surgical site infections among patients undergoing cardiac, hip, or knee surgery. JAMA. 2015 Jun 2;313(21):2162-71. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.5387. PMID: 26034956.

- Suzuki H, Perencevich EN, Hockett Sherlock S, et. al. Implementation of a Prevention Bundle to Decrease Rates of Staphylococcus aureus Surgical Site Infection at 11 Veterans Affairs Hospitals. JAMA Netw Open. 2023 Jul 3;6(7):e2324516. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.24516. PMID: 37471087; PMCID: PMC10359960.