Equal-Access Healthcare System Mitigates Many Disparities

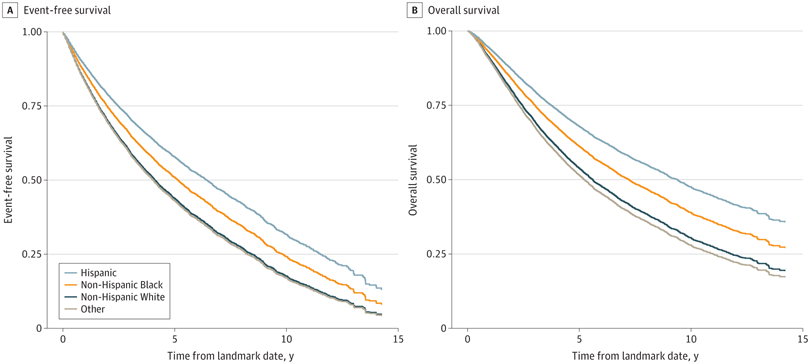

Click to Enlarge: Metastasis-free (A) and overall (B) survival. The numbers at risk are not available for adjusted survival curves, because the survival curves are adjusted proportionally with the confounders. The original numbers at risk would not correctly reflect the curves. The same algorithm we used to create survival curves does not provide numbers at risk, because the scaling is working on survival probabilities. To our knowledge, there are no existing algorithms to scale the number of people in such cases. Other includes American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, unknown by patient, and patient declined to answer. Source: JAMA Network Open

SALT LAKE CITY — While a new study found that differences in outcomes from nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer (nmCRPC) exist based on race and ethnicity, Black and Hispanic men might have considerably improved survival rates when treated in an equal-access setting.

The cohort study of 12,992 U.S. military veterans with nmCRPC treated in the VA healthcare system determined that self-identified Hispanic and non-Hispanic Black patients had improved clinical outcomes compared with their non-Hispanic White counterparts. Results were published in JAMA Network Open.1

“The findings of this study suggest that the availability of equal-access care may reduce and even reverse racial and ethnic disparities in patients with nonmetastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer,” wrote researchers from the University of Utah School of Medicine, the George E. Wahlen Veterans Health Administration, both in Salt Lake City, and colleagues.

The authors suggested that racial and ethnic disparities in prostate cancer are poorly understood, adding, “A given disparity-related factor may affect outcomes differently at each point along the highly variable trajectory of the disease.”

To better understand that, they sought to examine clinical outcomes by race and ethnicity in VHA patients with nmCRPC. The retrospective, observational cohort study used VA electronic healthcare records from Jan.1, 2006, to Dec.31, 2021. Mean (SD) follow-up time was 4.3 (3.3) years.

Included in the analysis were men diagnosed with prostate cancer from Jan. 1, 2006, to Dec. 30, 2020, that progressed to nmCRPC. Of the patients in the cohort, 56% were non-Hispanic white, 28% non-Hispanic Black and 6% Hispanic, with 9% being of other race or ethnicity or unknown.

Progression to nmCRPC was defined by (1) increasing prostate-specific antigen levels, (2) ongoing androgen deprivation and (3) no evidence of metastatic disease. Defined as the primary outcome was time to death or metastasis; the secondary outcome was defined as overall survival.

Results indicated that the median time elapsed from nmCRPC to metastasis or death was 5.96 (95% CI, 5.58-6.34) years for Black patients, 5.62 (95% CI, 5.11-6.67) years for Hispanic patients, 4.11 (95% CI, 3.96-4.25) years for white patients and 3.59 (95% CI, 3.23-3.97) years for other patients.

Researchers reported that the median unadjusted overall survival was 6.26 (95% CI, 6.03-6.46) years among all patients, 8.36 (95% CI, 8.0-8.8) years for Black patients, 8.56 (95% CI, 7.3-9.7) years for Hispanic patients, 5.48 (95% CI, 5.2-5.7) years for white patients and 4.48 (95% CI, 4.1-5.0) years for other patients.

Differences in Outcomes

“The findings of this cohort study of patients with nmCRPC suggest that differences in outcomes by race and ethnicity exist; in addition, Black and Hispanic men may have considerably improved outcomes when treated in an equal-access setting,” the study team wrote.

Background information in the article noted that health disparities by race and ethnicity are well documented in the United States. “Discrimination, adverse social determinants of health, and structural racism all contribute to such disparities, and members of historically marginalized groups can face many barriers to equitable health services, such as inadequate insurance and poor access to care, including culturally appropriate care,” the article stated. It’s also adding that minority groups might have different rates of prevalence of clinical and genetic prognostic and predictive markers compared with the general population yet their historic and ongoing underrepresentation in clinical trials makes that information difficult to access.

The report also pointed out that prostate cancer is the most common noncutaneous cancer among men in the U.S., making up an estimated 27% of new cancer diagnoses, while being second only to lung cancer in cancer-related mortality among those men.

In fact, it added that 1 in 8 men in the U.S. will be diagnosed with PC during his lifetime. But the mortality risk remains unequal, the researchers emphasized, explaining, “Black men are more than twice as likely to die of PC-related causes than white men, and mortality rates among Black men treated for PC remain higher than in men of other races even after adjusting for age, stage at diagnosis, insurance status, educational level, household income, comorbidities, and other clinical and nonclinical factors. Black men are more likely than men of other races and ethnicities to be diagnosed with PC, are diagnosed at a younger age, and have a higher incidence of distant-stage disease at diagnosis. n addition, Black men with local-stage disease face a higher risk of progression after treatment.”

The authors went on to state that various molecular, genetic, environmental and even psychological factors have been suggested as causes of the disparities.

The article advised that, as a “notably heterogeneous disease,” prostate cancer disease state and biological characteristics affect patient’s quality of life, survival and need and type of treatment. It added that each phase requires different diagnostic, surveillance and treatment modalities.

“Given this heterogeneity, it is likely that a given disparity-related factor may affect outcomes differently at each point along the disease’s highly variable trajectory,” the researchers suggested. “The factors determining whether a patient is screened for PC may well differ from those determining whether they safely undergo active surveillance and differ from the factors leading to the choice to receive second-generation hormonal therapy in the event that they progress to high-risk, castration-resistant disease. Thus, we argue that it is appropriate—and indeed, necessary—to investigate potential disparities at each key milestone of the disease rather than solely at diagnosis.”

They explained how equal-access healthcare systems seek to address financial barriers to healthcare and “are generally thought to mitigate, although not eliminate, health disparities” The VHA, for example, provides low-cost care to U.S. military veterans, including services to facilitate access, such as transportation and extended clinic hours. It is the largest equal-access system in the United States.

The current analysis varies from previous studies because it focused on nmCRPC, a “critical point in the trajectory of PC,” according to the authors. It also adjusted for key clinical factors that could act as confounders, such as patient characteristics, comorbidities, disease risk as captured by a PSADT at the time of castration resistance, and treatment received.

“The results of our analysis not only add to evidence that differences in PC outcomes by self-identified race and ethnicity exist, they suggest that Black and Hispanic men may actually have considerably improved outcomes compared with men of other races or ethnicities when treated in an equal-access setting,” the study concluded, adding, “These findings add to the growing body of evidence that suggests that treatment in an equal-access health care system may eliminate—or even reverse—some of the higher risks of poor outcomes long observed in Black men with PC.”

- Rasmussen KM, Patil V, Li C, et al. Survival Outcomes by Race and Ethnicity in Veterans With Nonmetastatic Castration-Resistant Prostate Cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(10):e2337272. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.37272