PHILADELPHIA — It’s long been said that “more men die with prostate cancer than from it.” While the statement remains true today, what treatment they receive appears to influence the cause of death.

Patients with prostate cancer are more likely to die of cardiovascular disease (CVD) than their initial cancer. That’s partly because prostate cancer often takes an indolent course and partly because prostate cancer and heart disease share a number of risk factors. It’s also because many men receive androgen deprivation therapy, which is associated with increased mortality from CVD.

A 2019 study found that 17% of men with prostate cancer died of CVD, while other research indicates that about 11% of men with the malignancy succumb to their cancer.1,2 Among men who had radical prostatectomies, CVD accounted for twice as many deaths as prostate cancer.3

Figuring out how much of the risk comes from the choice of therapy and how much from other risk factors is a significant concern for oncologists in general, but nowhere more than at the VA.

As the country’s largest integrated health care system, “it captures about 6% of all prostate cancer patients in the entire country,” said Stephen Freedland, MD, director of The Center for Integrative Research in Cancer and Lifestyle, professor of urology at Cedars-Sinai, and staff physician at the Durham VAMC in a recent video discussion. About 15,000 veterans are diagnosed with prostate cancer each year.

The high rate of prostate cancer among patients who receive care through the VA can be attributed to multiple factors. Prostate cancer prevalence increases with age, with 50% to 60% of men over age 80 having indicative tumors on autopsy, and VA patients tend to be older and male. The cancer also is a presumptive condition for veterans exposed to Agent Orange.

Hormone therapy or androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) is frequently used alone or in a combination therapy to treat high-risk early prostate cancer as well as recurrent, advanced or metastatic cancer. It also may be used in conjunction with radiation or surgery. Many patients continue on ADTs for years.

While initially effective in slowing cancer progression, ADTs increase the risk of dyslipidemia, sarcopenic obesity, insulin resistance and incident diabetes, sudden cardiac death, coronary artery disease, long QT interval, cerebrovascular disease and venous thromboembolism.

Guideline Recommendations

Since 2010, organizations including the American Heart Association, American Cancer Society and American Urologic Association have recommended that all prostate cancer patients beginning ADTs should be evaluated for cardiovascular risk factors (CVRF). Steps should be taken to mitigate risks in those that have them, including managing blood pressure, cholesterol, diabetes and recommending lifestyle changes.

More than 10 years later, it appears many men with prostate cancer are still not evaluated for cardiovascular disease. Is that true at the VA as well? Researchers at the Corporal Michael J. Crescenz VAMC in Philadelphia and the VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System, along with scientists at the University of Pennsylvania, sought to find out.

In a study published in JAMA Network Open, the researchers conducted a retrospective analysis of the records of 90,494 men treated at VA facilities for prostate cancer between Jan. 1, 2010, and Dec. 31, 2017. Of those, 22,700 veterans received ADT.4

They found that cardiovascular risk factors were both underassessed and undertreated in veterans with prostate cancer and that, despite recommendations, the initiation of ADT did not significantly increase the likelihood of comprehensive risk factor evaluation or treatment for those risks.

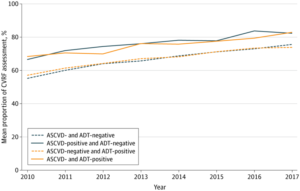

Overall, 68.1% of the men received comprehensive cardiovascular risk factor assessment, as indicated by recorded blood pressure, lipid levels and glucose levels. The evaluation rate rose during the period studied from 57.9% to 76.8%, largely as a result of the VA’s increased screening for diabetes, according to the authors. White men were less likely than nonwhites to have risk assessments, and veterans with metastatic prostate cancer were 7.4% less likely to have a comprehensive risk analysis, although they were the most likely to receive ADT.

A history of cardiovascular disease was associated with about a 10-point increase in risk factor assessment, regardless of whether the patient was prescribed ADTs, 76.2%-78.2% vs. 65.8%-68.8%, indicating that evaluation of risk factors was driven more by known cardiovascular disease (CVD) than initiation of ADT.

Of the veterans with comprehensive assessments, more than half (54.1%) had at least one uncontrolled risk factor. More than one-third (35.7%) had uncontrolled blood pressure. About 1 in 5 had uncontrolled blood pressure, and 19.1% had uncontrolled glucose levels. The researchers defined controlled risk factors as blood pressure lower than 140 mm Hg/99 mm Hg, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol less than 130 mg/dL, and hemoglobin A1c less than 7%.

Three in 10 veterans with uncontrolled risk factors did not receive medications to reduce their risk. Specifically, 21.3% of those with high blood pressure did not receive antihypertensives, and nearly half (47.6%) of those with uncontrolled cholesterol were not prescribed statins. Among veterans with elevated glucose levels, 8.1% did not receive a diabetes medication.

Treatment for these risk factors was most likely in veterans with a history of CVD, who had a more than 20% lower risk of being untreated, regardless of ADT status, compared to those without a CVD diagnosis. Among men without a CVD history, those who initiated ADT had only a 5.4% decrease in the likelihood of an untreated risk factor compared to those who did not start ADT.

“Rates of incomplete assessment remained high, with more than one in five veterans not receiving comprehensive CVRF assessment even in recent years,” the authors said. “We also found a high burden of modifiable risk factors at baseline: more than three-quarters were overweight or obese; more than half had uncontrolled blood pressure, cholesterol, and/or glucose levels; and more than a quarter of these patients were not receiving corresponding risk-reducing medications.”

While recognizing that veterans with CVD may be at higher risk for cardiac events, the authors noted that they did not detect greater risk management intensity. Further, “although cardiac risk was assessed and managed more closely in veterans with a history of ASCVD, initiation of ADT was not associated with meaningfully higher rates of CVRF assessment or treatment, despite increasing awareness and consensus statements regarding the cardiovascular effects of ADT.”

The findings fell in line with previous study results showing high rates of cardiovascular risk in men with prostate cancer and failure to assess and treat risk factors in men initiating ADT. The researchers suggested that the side effects of ADT may occupy much of a clinician’s time during patient visits, pushing serious but asymptomatic cardiometabolic effects to the side. They concluded that “because monitoring and mitigation of CVRFs are essential to improving survivorship care in patients with prostate cancer, most of whom are treated with curative intent and have prolonged life expectancies, our findings underscore the need for improved clinician and patient education, as well as interventions to optimize cardiac risk management.”

- Sturgeon KM, Deng L, Bluethmann SM, Zhou S, Trifiletti DM, Jiang C, Kelly SP, Zaorsky NG. A population-based study of cardiovascular disease mortality risk in US cancer patients. Eur Heart J. 2019 Dec 21;40(48):3889-3897. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehz766. PMID: 31761945; PMCID: PMC6925383.

- Epstein MM, Edgren G, Rider JR, Mucci LA, Adami HO. Temporal trends in cause of death among Swedish and US men with prostate cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2012 Sep 5;104(17):1335-42. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djs299. Epub 2012 Jul 25. PMID: 22835388; PMCID: PMC3529593.

- Shikanov S, Kocherginsky M, Shalhav AL, Eggener SE. Cause-specific mortality following radical prostatectomy. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 2012 Mar; 15(1):106-10.

- Sun L, Parikh RB, Hubbard RA, et al. Assessment and Management of Cardiovascular Risk Factors Among US Veterans With Prostate Cancer. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e210070. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.0070