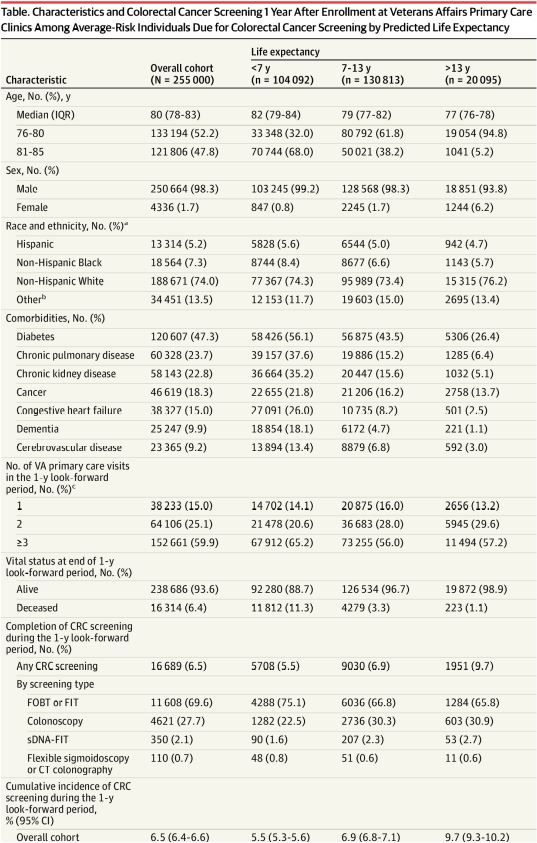

Click to Enlarge: Characteristics and Colorectal Cancer Screening 1 Year After Enrollment at Veterans Affairs Primary Care Clinics Among Average-Risk Individuals Due for Colorectal Cancer Screening by Predicted Life Expectancy Abbreviations: CRC, colorectal cancer; CT, computed tomography; FIT, fecal immunochemical test; FOBT, fecal occult blood test; sDNA-FIT, stool DNA with fecal immunochemical test; VA, Veterans Affairs.

a. Race and ethnicity were assessed to understand the demographic profile of individuals in Veterans Affairs primary care clinics and were categorized as Hispanic, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic White, and other using the Research Triangle Institute beneficiary race code from the Medicare Master Beneficiary Summary File. This variable incorporates information on race and ethnicity from the Social Security Administration and subsequently applies an algorithm developed to improve the accuracy of coding for Asian and Other Pacific Islander and Hispanic beneficiaries based on surname and geography.

b. Other includes American Indian/Alaska Native, Asian and Other Pacific Islander, and unknown.

c. All individuals had at least 1 VA primary care visit in 2018 to be eligible for the cohort. These numbers represent the number of visits, inclusive of this initial 2018 index visit. Source: JAMA Network Open

SAN FRANCISCO – Even though clinical guidelines recommend that clinicians selectively offer colorectal cancer (CRC) screening to older adults aged 76 to 85 years, taking into account their life expectancy, values, and preferences. That does not appear to be occurring in the VA healthcare system, however, according to new research.

A research letter published in JAMA reported that CRC screening was uncommon in veterans aged 76 to 85 years in 2018-2019. Furthermore, the rates varied only slightly by predicted life expectancy, according to authors from the San Francisco VA Healthcare System.1

“These results suggest that clinicians may not be selectively targeting CRC screening to a small subset of healthy older adults with long life expectancies who may benefit from continued screening,” the study team wrote.

Previous research has suggested that few adults older than 75 years receive CRC screening, according to the authors, which raised concerns that healthy adults older than 75 aren’t being screened, even though they might accrue some benefit.

That’s why the researchers sought to determine CRC screening varied by predicted life expectancy in a national sample of VA patients. Included were veterans aged 76 to 85 years enrolled in VA primary care clinics with one visit or more in 2018. All were due for CRC screening and at average risk for CRC.

Life Expectancy Prediction

Each individual’s life expectancy was predicted using a VA electronic health record–based life expectancy calculator that performed well on discrimination and calibration in this age group, and stratified individuals based on life expectancy of less than 7 years (unlikely to benefit from screening), 7 to 13 years (possible benefit from screening), and more than 13 years (potential benefit from screening).

Defined as the primary outcome was completion of any type of CRC screening, excluding tests for non-screening indications. To determine that, the study team used VA and Medicare claims data during a one-year look-forward period from the 2018 index primary care visit (final follow-up date: December 31, 2019).

Ultimately, the final cohort included 255 000 veterans with a median age of 80; most, 98.3% were male and 7.3% were non-Hispanic Black.

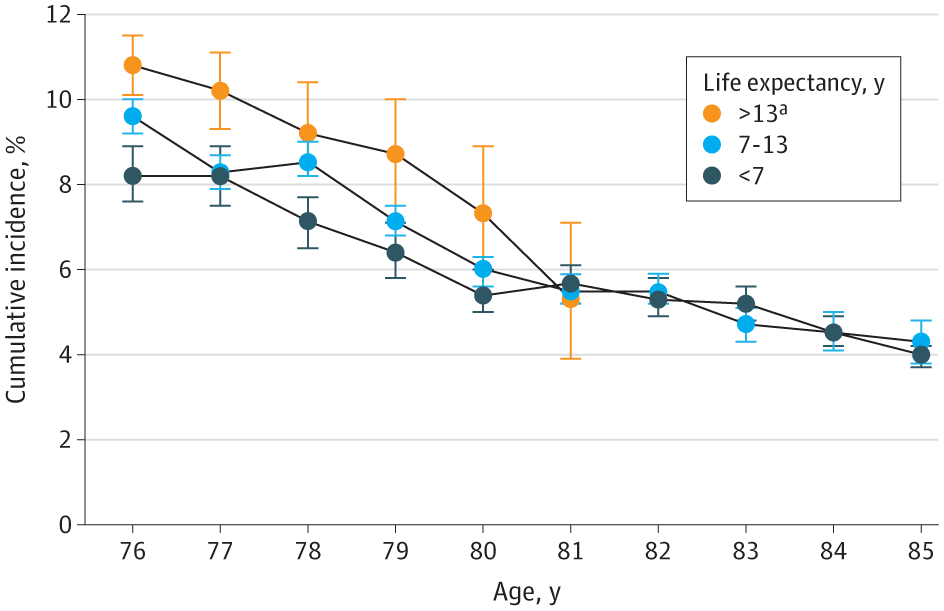

The researchers noted that, during the 1-year look-forward period, 20 628 veterans (8.1%) underwent any CRC test, of which 16 689 (6.5%) underwent tests classified as screening. According to the results, the cumulative incidence of CRC screening among those with life expectancy of less than 7, 7 to 13, and more than 13 years was 5.5% (95% CI, 5.3%-5.6%), 6.9% (95% CI, 6.8%-7.1%), and 9.7% (95% CI, 9.3%-10.2%), respectively. “Within the 76- to 80-year age group, the cumulative incidence of CRC screening among those with life expectancy of less than 7, 7 to 13, and more than 13 years was 7.0% (95% CI, 6.8%-7.3%), 8.0% (95% CI, 7.9%-8.2%), and 9.9% (95% CI, 9.5%-10.4%), respectively,” the study pointed out.

“While guidelines specifically mention life expectancy in screening decisions, clinicians often do not make use of this information in part because it is often not readily available,” the authors advised. “Automated electronic health record–embedded life expectancy calculators that identify individuals 76 to 85 years with more than 13-year life expectancies could help focus shared decision-making conversations to those most likely to benefit.”

Click to Enlarge: Unadjusted Cumulative Incidence of Colorectal Cancer Screening in Older Adults Aged 76-85 Years Due for Colorectal Cancer Screening Over the 1-Year Look-Forward Period by Age and Stratified by Predicted Life Expectancya The life expectancy line for >13 years ends at age 81 years because of small sample sizes, with wide confidence intervals at ages 82 years and older. Source: JAMA Network Open

They added that life expectancy calculators could also identify patients 76 to 85 years with less than 7-year life expectancies; in that cohort, screening might be more likely to cause harm, the researchers cautioned.

“Future studies should test whether life expectancy–directed CRC screening in those aged 76 to 85 years improves outcomes,” according to the report. “Study limitations include the predominantly male VA population, which may limit generalizability for older women and individuals outside the VA.”

- Deardorff WJ, Lu K, Jing B, et al. Frequency of Screening for Colorectal Cancer by Predicted Life Expectancy Among Adults 76-85 Years. JAMA. 2023;330(13):1280–1282. doi:10.1001/jama.2023.15820