WASHINGTON — The VA joined several other major players in the health care market in deciding not to add the recently approved—and controversial—Alzheimer’s drug aducanumab (Aduhelm) to its national formulary.

The VA’s Pharmacy Benefits Management group explained the decision based on “the lack of evidence of a robust and meaningful clinical benefit and the known safety signal.” Despite these concerns, VA policy allows providers to request coverage on an individual basis for patients whose MRI scans confirm the presence of beta amyloid plaques. In addition, patients must be tested to ensure they do not have a gene associated with brain swelling in clinical trials and do not have a history of bleeding disorders and are not on blood thinners.

To be treated at the VA, a patient must be under the care of “experts and centers that have the necessary diagnostic and management expertise—and only by those with the needed resources for close monitoring to assure safety.”

The drug received conditional U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in June despite the nearly unanimous rejection of the manufacturer’s application by the agency’s Independent Peripheral and Central Nervous System Drugs Advisory Committee. As part of the approval, the FDA required a confirmatory, phase IV, trial to show clinical benefit, though the manufacturer has nine years to complete that trial.

Three advisory committee members resigned following the FDA’s approval. One of them, Aaron Kesselheim, MD, JD, MPH, a professor at Harvard Medical School and director of the program on regulation, therapeutics, and law at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, calling it the “probably the worst drug approval in recent US history,” in his resignation letter.

Controversial Approval

Aducanumab, a monoclonal antibody, originally received broad approval for use in the treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Three weeks later, following a storm of criticism, the FDA added restrictions to the indication that limited it to use in patients who have mild cognitive impairment or mild dementia. Unlike the clinical trials, the FDA did not exclude patients who lack proof of amyloid plaques.

In mid-July, FDA Acting Director Janet Woodcock, MD, called for an investigation by the Department of Health and Human Services’ Office of the Inspector General into possible irregularities in the drug’s approval process and communications between the agency and aducanumab’s manufacturer. Several members of Congress have also called for an investigation. The OIG investigation is not expected to wrap up until 2023.

The crux of the controversy concerns the issues identified in the VA’s determination to keep the drug off the national formulary. The initial results of the two big studies submitted to the FDA were so lackluster that the manufacturer terminated them in 2019. Months later, the company announced that a reanalysis of one of the studies showed a modest potential delay of cognitive impairment. The company was unable to explain to the FDA advisory committee why the other trial, with an identical patient population and trial protocols, reached the opposite conclusion, finding no clinical benefit to the drug.

The FDA approval noted that aducanumab demonstrated an ability to clear beta amyloid plaques, which it considered a reasonable proxy for clinical benefit, despite having rejected clearance as an indicator of clinical benefit previously. Beta amyloid plaque accumulation in the brain is one of the earliest physical signs of Alzheimer’s disease, but not everyone with the plaques will go on to develop dementia. More controversially, several other drugs including solanezumab and bapineuzumab that previously demonstrated the ability to clear beta amyloid plaques were unable to show any clinical benefit.

In addition to not clearly providing a clinical benefit, the aducanumab trials identified a serious safety concern, neurotoxicity that substantially increased the risk of brain bleeds and brain swelling.

Other Coverage Decisions

The combination of no clear benefit, significant safety concerns, and the drug’s high cost at $56,000 per year led a number of leading health care organizations and insurance plans to refuse to use or cover aducanumab at this point. Those include the Cleveland Clinic, Mount Sinai, and Blue Cross Blue Shield affiliates in New York, Pennsylvania, Florida, Michigan, North Carolina, Kansas which noted that “a clinical benefit has not been established.” Several other organizations such as The Mayo Clinic and Massachusetts General Brigham Hospital are working through their own approval processes before deciding whether to infuse the drug in their patients.

Further, rather than immediately covering aducanumab as it does nearly all drugs that receive FDA approval, the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services instead decided to undertake a national coverage determination process, which it projects will not be completed until April 2022. While regional Medicare contractors could set their own policies before the national decision is made, most appear to have decided to wait for the national decision. Whatever CMS decides could affect other monoclonal antibodies in the pipeline to treat Alzheimer’s, including donanemab and gantenerumab, two other beta amyloid-targeting therapies.

CMS could restrict coverage to particular types of patients, such as those with evidence of amyloid plaques, require repeated monitoring scans, or limit use to trials, among other options. As about 85% of patients with Alzheimer’s disease, including most veterans, have Medicare coverage, the cost to the agency could be huge. The Kaiser Family Foundation estimates that use in eligible patients with mild dementia could cost CMS a budget-busting $29 billion, about the cost of all other drugs CMS currently covers combined.

The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review (ICER)’s report on aducanumb called into question the value of the drug for most patients, particularly in light of the financial toxicity it poses.

“The clinical trial history and evidence regarding aducanumab are complex,” said David Rind, MD, ICER’s chief medical officer. “We have spent eight months analyzing the study results, talking with patient groups and clinical experts, and working with the manufacturer to understand their position. At the conclusion of this effort, despite the tremendous unmet need for new treatments for Alzheimer’s disease, we have judged the current evidence to be insufficient to demonstrate that aducanumab slows cognitive decline, while it is clear that it can harm some patients.”

But, ICER noted, with FDA approval, many patients will line up to get infusions of the drug, without any idea of whether it will benefit them and at huge financial cost. In addition to the price of the drug itself, imaging, doctor’s visits, and other charges will likely push the cost of infusions over $100,000 annually. “The company had another path open to them,” Rind said. “They could have priced in line with our current best estimate of clinical value at a tenth of their current list price and still expected to make billions of dollars each year.” ICER’s health-benefit price benchmark range for aducanumab ranged from $3,000 to $8,400.

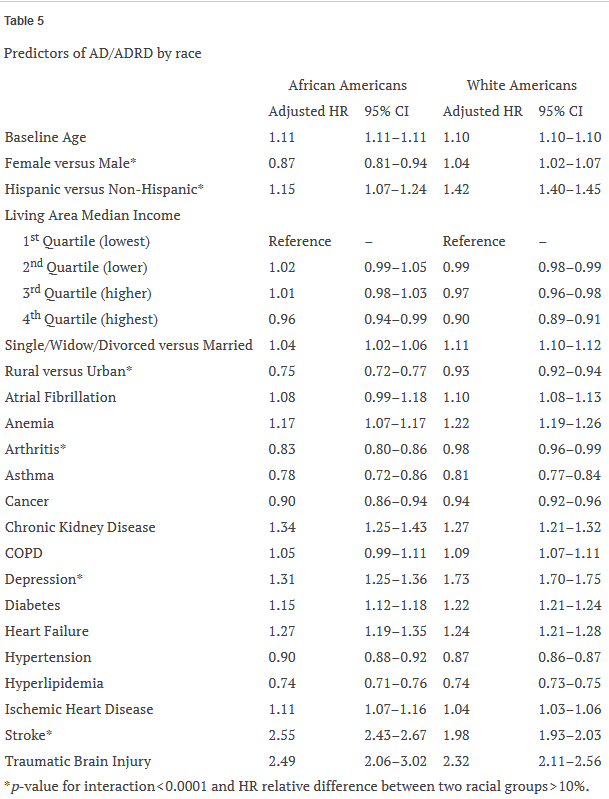

- Alzheimer’s Disease and Alzheimer’s Disease-Related Dementias in Older African American and White Veterans. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;75(1):311-320. doi: 10.3233/JAD-191188. PMID: 32280090; PMCID: PMC7306894.