Strong Emphasis on Behavioral Health Screening Before Prescribing

WASHINGTON, DC — Recent VA/DoD guidelines call for new measures to reduce the use of opioid pain relievers in the management of chronic pain, including the preferential use of buprenorphine over full agonist opioids.

The 2022 updated guideline also urged physicians to assess for behavioral health risk when considering prescribing opioids, including screening patients with acute pain for pain catastrophizing, such as anticipating that pain will last an extended period of time. It also suggested that clinicians offer education before surgery to help reduce the risk of opioid painkillers overuse during the recovery period.

Many of the previous recommendations were confirmed by the latest guideline development group, including not recommending the use of opioids in the daily management of chronic pain because the benefits are small and outweighed by risks to the patient. If opioids are required, they write, the lowest possible dose for the shortest amount of time should be used.

A synopsis of the guidelines, approved last year by VA and DoD leadership, appeared last month in the Annals of Internal Medicine. The authors said the report highlighted the recommendations they considered most important.1

In December 2020, the VA/DoD Evidence-Based Practice Work Group put together a team to update the 2017 VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for Opioid Therapy for Chronic Pain.

“Chronic pain is a common, costly, and disabling medical condition in the United States,” according to background information in the synopsis. “It has been estimated that nearly 50 million adults experience chronic pain on most days or every day pain is also associated with approximately 20% of all ambulatory primary care and specialty visits in the United States.”

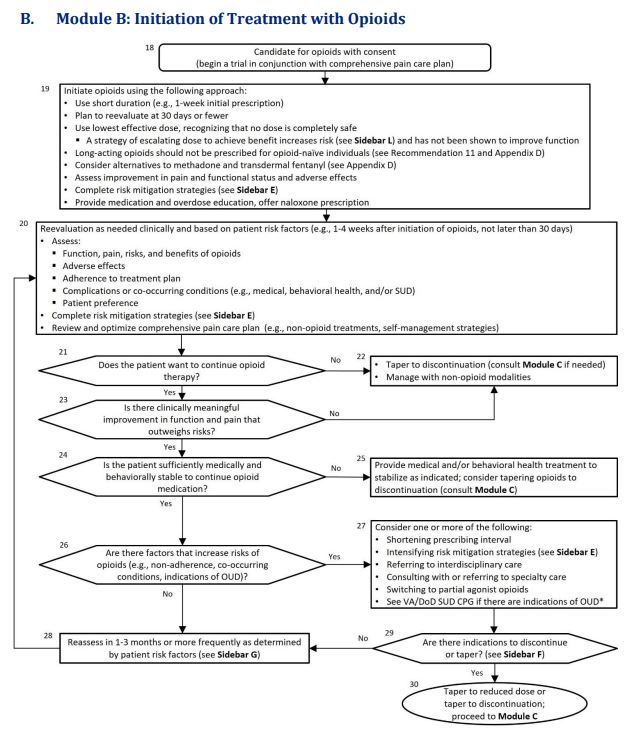

Click to Enlarge: Abbreviations: OUD: opioid use disorder; SUD: substance use disorders; VA/DoD SUD CPG: VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Substance Use Disorders Source: VA/DoD Clinical Practice Guideline

The report recounted how, beginning in the late 1990s until 2008, there was a significant increase in prescribing of opioids for pain relief—and an accompanying jump in opioid-related morbidity and mortality, overdose death and admissions for treatment of substance use disorder. Since then, the VA and DoD have been at the forefront of trying to reduce overuse of opioid pain medications.

The guideline panel included practicing clinicians in a range of specialties, including internal medicine, family medicine, neurology, nursing, pharmacy, psychology, physical therapy, social work, acupuncture and Chinese medicine and chiropractic and interventional medicine.

Among the key changes from the previous 2017 document, in addition to those listed above, is that treatment algorithms, which help guide clinicians through decision-making processes, have been updated and condensed so that there are now 3 rather than 4, as in the previous 2017 guideline.

As in past guidelines, the recent panel recommended against the initiation of opioid therapy for the management of chronic non-cancer pain. “Compared with the 2017 recommendation against initiation of long-term opioid therapy, the updated recommendation against opioid therapy in general for chronic pain is broader and reflects the evidence that opioid therapy for any duration may be harmful,” according to the authors. Citing recent research used in developing the new guidelines, they added, “Although opioids can improve pain severity and functional status in some patients with musculoskeletal pain, including chronic low back pain and osteoarthritis in studies of 4 to 24 weeks’ duration, the effects are small, are accompanied by adverse events, and are generally believed to be without important benefit on pain or function.”

Potential for Catastrophic Harms

Despite finding some evidence for a small improvement in musculoskeletal and non-cancer neuropathic pain, the guideline development group determined that “the potential for catastrophic harms of opioids and serious adverse events, especially with long-term use, outweighed any potential benefits of temporarily improved pain severity and functional status in patients with chronic pain.”

In cases where, based on a clinical assessment, an opioid pain reliever is necessary buprenorphine, a partial µ-opioid receptor agonist with analgesic properties, is recommended. The panel pointed out that the drug has a lower risk for overdose and misuse.

“Although the guideline development group found very little evidence on the comparative effectiveness of buprenorphine and other full agonist opioids for the management of chronic pain, buprenorphine has a superior safety profile, especially for respiratory depression, even in non-dependent persons and fatal overdose. In addition, excluding those who are opioid-naive, buprenorphine is less likely to cause euphoriant effects and is a first-line treatment of opioid use disorder (OUD),” the article explained, citing recent studies.

In line with the previous 2017 guideline, the guideline authors also advised using the lowest dose as indicated by patient-specific risks and benefits when prescribing an opioid. They said their rationale is that, while the risk for prescription opioid overdose and overdose death exists even at low opioid dosage levels, it “increases with increasing opioid doses. There is a dose-related risk for OUD: Patients receiving 20 to 50 morphine milligram equivalents had a lower risk than those prescribed greater than 200 morphine milligram equivalents. Both the initiation of opioids in the opioid-naive patient and opioid dose escalation in patients receiving long-term opioids are associated with opioid misuse, development of OUD, and overdose.”

In a similar vein, the new guideline agreed with the previous version in recommending the shortest duration as indicated when prescribing opioids Long duration, it said, is associated with a higher risk of OUD and fatal overdoses.

The updated guideline also strongly urged reevaluation at 30 days or less after initiating opioid therapy and frequent follow-up visits if opioids are continued, adding,. “Follow-up allows clinicians to review and adjust the pain care plan, including continuing the use of opioids.”

Long-acting opioids are not recommended for treating acute pain, for as-needed pain or when initiating long-term opioid therapy, because of the higher risk of developing an opioid use disorder. That is in line with recent U.S. Food and Drug Administration recommendations.

“In general, however, no single opioid or opioid formulation is preferred over the others. There is limited evidence about the comparative effectiveness and safety of various opioid formulations,” the guideline pointed out.

While the 2017 document urged the assessment of the risk of suicide and self-directed violence when initiating, continuing, changing or discontinuing long-term opioid therapy, the update also recommended assessing for behavioral health conditions, history of traumatic brain injury and psychological factors (for example, negative affect, pain catastrophizing) “because these conditions are associated with a higher risk for harm.”

This updated guideline also includes a new recommendation for screening for pain catastrophizing and co-occurring behavioral health conditions in patients with acute pain. It is based on evidence from four large retrospective and retrospective cohort studies finding that “patients with acute pain and co-occurring behavioral health conditions are at increased risk for opioid dependence, overdose, death, and potentially obtaining inappropriate prescriptions.”

The authors also cited research showing that, when patients anticipate that their pain will last longer than a week, they have higher rates of persistent pain. A non-opioid analgesic might be more appropriate for patients who have a positive screen, according to the guideline.

The panel conceded, “There are some risks associated with screening patients for pain catastrophizing and co-occurring behavioral health conditions. Some patients may feel a stigma associated with this type of diagnosis. This is especially true for military patients where there may be career implications for a positive screen result.”

- Sandbrink F, Murphy JL, Johansson M, et al; VA/DoD Guideline Development Group. The Use of Opioids in the Management of Chronic Pain: Synopsis of the 2022 Updated U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs and U.S. Department of Defense Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Intern Med. [Epub 14 February 2023]. doi:10.7326/M22-2917