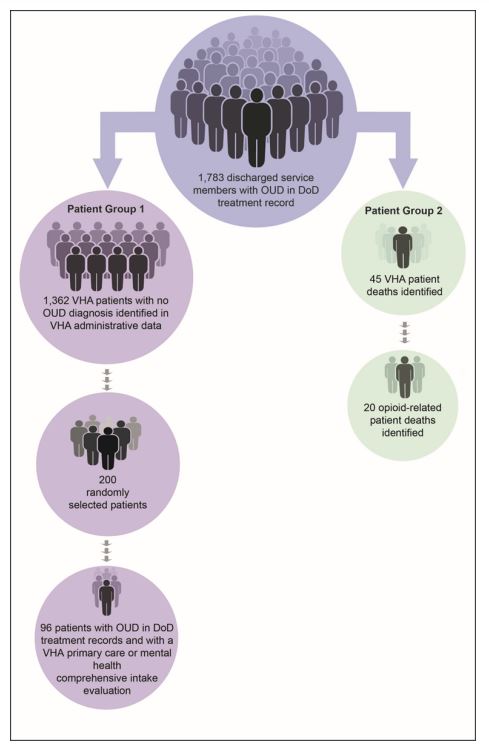

Click to Enlarge: Study population, Patient Group 1, and Patient Group 2 for this review.

Source: The OIG developed this figure based on scope and methodology for this review.

Note: Due to both Patient Groups 1 and 2 being from the original study population of 1,783, a patient could be in both Patient Group 1 and Patient Group 2. Source: VA Office of Inspector General

WASHINGTON, DC — Veterans with opioid-use disorder (OUD) are at an increased risk for overdose and suicide in the year following discharge. For this reason, VA and DoD place a high value on the firm handoff of patients.

A recent report has found, however, that significant gaps still remain, and a large percentage of OUD patients are going unnoticed and untreated.

In 2020, opioids were responsible for approximately 75% of all overdose-related deaths in the United States. A 2021 study found that veterans are twice as likely to die from accidental overdose compared with nonveterans. Failure to identify a patient’s known history with opioids and make a relevant treatment plan could increase that risk even further.

“There are challenges within the first 12 months after discharge from DoD associated with leaving active duty and transitioning to civilian life,” a recent report from the VA Office of the Inspector General states. “[Those include] homelessness, reintegrating with family, employment, substance mismanagement, and the risk of suicide.”

In response to the needs of transitioning servicemembers, DoD, DHS and VA created a joint action plan meant to create “seamless access to mental health treatment and suicide prevention resources … in the year following discharge.”

That plan emphasizes the importance of identifying patients with risk factors, including OUD, who require additional support. Still, hundreds of servicemembers with OUD diagnoses in their DoD records enter VA without that information being carried over to their VA healthcare record.

OIG investigators looked at a sampling of 1,783 servicemembers discharged between 2016 and 2019 who had been diagnosed with OUD during their time in the military. Of those, 1,362 have since become patients at VA while failing to have that OUD diagnosis identified in their VHA administrative data.

Within that original 1,783 patient sampling, OIG also identified 45 VA patients who have since died. Twenty of those deaths were opioid-related.

VA providers are expected to evaluate a patient’s substance use history when completing their comprehensive intake evaluation, which occurs when they transition into VA care. Any information regarding OUD should be documented in their record at that time.

Among that group of 1,362 patients who failed to have their OUD diagnosis identified, 19% had a note by a VA physician regarding opioid use in the records of that comprehensive intake report. However, none of them had OUD documented in the VHA problem list, which is used in electronic health records to identify problems related to a patient’s health.

Investigators also found that, when questioning VA physicians, less than half of them had any expectation of reviewing DoD treatment records when completing the intake process. Of those physicians who did access the DoD treatment records, more than half reported difficulties in using the Joint Longitudinal Viewer (JLV)—the system that allows VA physicians to access a read-only version of DoD healthcare records. Those barriers included issues related to navigation, timeliness of information, inadequate search functions, and provider time constraints. Only 45% of physicians reported receiving any training on the use of the JLV at all.

This failure to identify veterans with a history of OUD could not only cause providers to fail to provide proper treatment but might lead to serious, sometimes catastrophic, errors.

Of those 1,362 still-living patients with a history of OUD, 3% were prescribed opioids at their first comprehensive intake evaluation. In that group of 20 patients who died from opioid-related overdoses, 25% were prescribed opioid medications. Of those five, all had OUD somewhere in their VHA progress notes, but only three had it marked in the VHA problems list.

In February 2021, VA issued a memorandum requiring naloxone be offered to patients with OUD who had an increased risk of death by overdose or suicide. However, of those 20 patients in the report sample who died from opioid overdose, only 35% were offered naloxone by a VA physician. Whether that low number is due to the lack of an established OUD diagnosis or a failure to understand or follow VA guidelines is unknown.

The OIG report makes several recommendations, most of which revolve around identifying the barriers that are keeping VA providers from learning and then documenting that new patients have a history of OUD and then implementing solutions to remove those barriers. VA leaders have agreed with all of the report’s recommendations and have created an action plan to put them into effect.