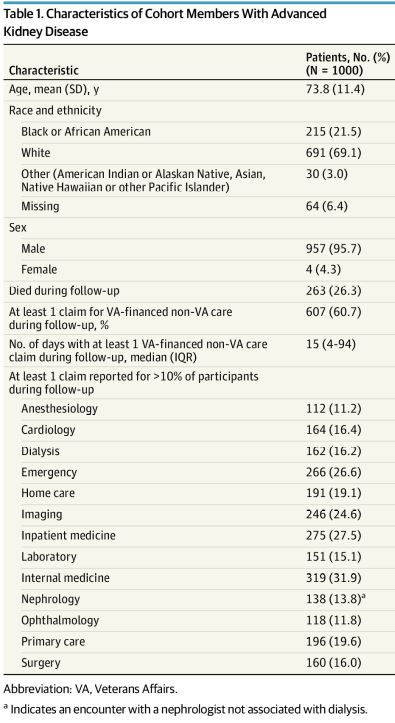

Characteristics of Cohort Members With Advanced Kidney Disease Abbreviation: VA, Veterans Affairs.

a. Indicates an encounter with a nephrologist not associated with dialysis.

WASHINGTON, DC — Since 2014, when Congress passed the Veterans Access Choice and Accountability (Choice) Act, the VA has been paying for U.S. veterans to receive increasing amounts of private sector, non-VA, care.

In 2018, the program was replaced by the more comprehensive Maintaining Internal Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks (MISSION) Act.

While the goal has been to make timely, high-quality care accessible to more veterans, a result has been increased stress on veterans and the VA system alike, a new study revealed.

The report published in JAMA Internal Medicine was funded by the VA Health Services Research and Development HSR&D program. HSR&D is an intramural research program that works to identify, evaluate, and rapidly implement evidence-based strategies that improve the quality and safety of care delivered to veterans.1

To better understand the effects of the marked increase in outsourcing of care to the private sector, researchers led by Ann M. O’Hare, MD, MA, of the University of Washington and the VA Puget Sound Healthcare System, used national VA data sources to identify a cohort of patients with advanced kidney disease who were alive at the time of MISSION Act rollout in July 2019.

“We then used an approach that our group has used to study a variety of other complex care processes to qualitatively analyze the VA-wide electronic health records of a sample of these patients,” said O’Hare, who is a professor of medicine at the University of Washington. “Our goal was to learn about the implementation of the MISSION Act by studying documentation in the VA-wide electronic health record.” The authors chose kidney disease patients as the focus of their study because those veterans are a high-need high-cost segment with a high degree of reliance on non-VA care, she said.

The cohort studied consisted of 1,000 participants with a mean age of 73.8. Overall, 607 (60.7%) cohort members had at least one active or paid claim for VA-financed non-VA care during follow-up. The search identified 583 with at least one mention (and a total of 2,792 mentions) of the term community care in clinical notes between June 6, 2019, and Feb. 5, 2021. From the analysis of documentation in patients’ VA-wide electronic health records, three themes emerged:

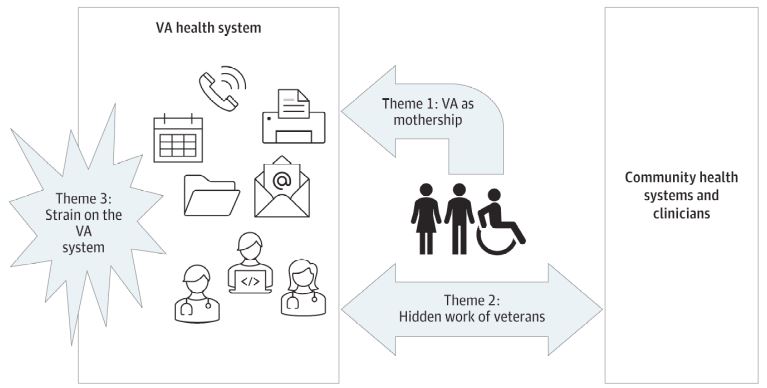

Thematic Schema for Qualitative Assessment Thematic schema based on assessment of documentation in patient electronic health records pertaining to VA-financed non-VA care. VA indicates Veterans Affairs. Illustration was designed by Janelle S. Taylor, PhD.

VA as the mothership, which describes extensive care coordination by VA staff members and clinicians to facilitate care outside the VA and the tendency of veterans and their non-VA clinicians to rely on the VA to fill gaps in this care.

Designated VA community care staff members were involved in a wide range of different tasks directing requests from non-VA clinicians and health systems to the relevant VA clinicians for authorization, furnishing non-VA clinicians with medical records for referred patients, coordinating between VA and non-VA clinicians to facilitate care, monitoring the care of veterans hospitalized outside the VA and coordinating transfers to the VA when needed, retrieving health records from non-VA health systems, and keeping patients’ VA clinicians informed about the care they were receiving outside the VA, the authors wrote.

Other staff members and clinicians not officially tasked with coordinating non-VA care were also engaged in less systematic efforts to support this care, which included helping veterans to access services both within and outside the VA that had been recommended by their non-VA clinicians, encouraging veterans to keep non-VA care appointments and helping to set up travel to non-VA appointments

The work of VA staff and clinicians to support VA-financed non-VA care was in part prompted by the tendency of veterans to turn to the VA for assistance with referrals for non-VA care and filling administrative and clinical gaps in the care they were receiving (or wished to receive) outside the VA, they wrote. There were also instances of veterans seeking the care of trusted VA clinicians to supplement or replace VA-financed care they were receiving outside the VA

Hidden work of veterans, which describes the efforts of veterans and their family members to navigate the referral process and to serve as intermediaries between VA and non-VA clinicians.

Despite the efforts of VA staff and clinicians, procurement of VA-financed non-VA care demanded substantial time and effort on the part of veterans and their families, the study found. The authors found examples of referrals that had been stalled or canceled due to the veteran not answering their phone or not responding to (or being confused by) calls they had received about their non-VA care. Veterans were expected to be proactive in initiating and maintaining the momentum of referrals. However, many struggled with the referral process and had difficulty accessing needed care, which could be time-consuming and anxiety-provoking.

Further, because the records and treatment recommendations of non-VA clinicians were frequently not available to VA clinicians in a timely fashion, veterans and/or their family members were required to serve as informants and messengers between their VA and non-VA clinicians. Veterans and/or their family members also provided VA clinicians with important contextual information about the care they were receiving or had received outside the VA.

Strain on the VA system, which describes a challenging referral process and the ways in which cross-system care has stretched the traditional roles of VA staff and clinicians and interfered with VA care processes.

There were multiple references in medical documentation to the time-consuming and inefficient nature of the community care referral process, the authors stated. By design, VA referrals for care outside the VA were time limited, the scope of services covered by each referral was prespecified, and referrals were intentionally canceled when veterans did not respond to telephone calls. Requests for continuation of services had to be authorized by VA clinicians as did any changes to, or expansion of, authorized services, and canceled consultations had to be resubmitted.

The high level of VA clinician oversight required by the referral process meant that VA Community Care and other support staff routinely routed referral requests to physicians for approval, bureaucratizing their clinical role. Efforts to accommodate the needs of veterans receiving care outside the VA also stretched the traditional roles of other VA clinical staff members.

Referring veterans to outside clinicians and health systems could also interact and conflict with VA care processes, the authors wrote, noting they also found examples of VA clinicians rearranging VA appointments to accommodate veteran appointments outside the VA. Changes or delays in the provision of non-VA care limited the ability of the VA to help coordinate or otherwise support this care, such as arranging transportation.

“The study shines a light on the internal impact of the MISSION Act on the VA system and characterizing some of the less tangible costs of outsourcing care,” O’Hare told U.S. Medicine. “The bottom line is that outsourcing of Veteran care to the private sector places a large burden on Veterans and their family members and VA staff and clinicians and is straining the VA system.”

The authors concluded, “these difficult-to-measure consequences of cross-system care should be considered when budgeting, evaluating, and planning the provision of VA-financed non-VA care in the private sector.”

“We hope that our findings will prompt policymakers to consider these somewhat hidden and untoward effects of outsourcing care on the VA system, and keep these in mind when making decisions about whether, when and how much to outsource Veteran care to the private sector,” O’Hare added.

- O’Hare AM, Butler CR, Laundry RJ, Showalter W, et. al. Implications of Cross-System Use Among US Veterans With Advanced Kidney Disease in the Era of the MISSION Act: A Qualitative Study of Health Care Records. JAMA Intern Med. 2022 May 16:e221379. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2022.1379. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35576068; PMCID: PMC9112136.