Many Older Veterans Don’t Benefit; Hypoglycemia Could Occur

BOSTON — About 10% of older veterans discharged from VAMCS had their diabetes medication intensified, even though half of them were unlikely to benefit because either they already had reached their blood glucose goals or had limited life expectancy.

That’s according to a report in JAMA Network Open which discussed the rate at which VHA patients are discharged with changes to their outpatient diabetes medication regimens after hospitalization for common medical conditions.

A study team from Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, the San Francisco VAMC and the University of California, San Francisco, conducted a cohort study of 16,178 older adults hospitalized in the VHA national health system, 1 in 10 patients was discharged with intensified diabetes medications.

The authors suggested that, during hospitalization, consideration of long-term diabetes control is needed in addition to inpatient blood glucose recordings to reduce potentially nonbeneficial medication changes when older patients are discharged home.

“Elevated blood glucose levels are common in hospitalized older adults and may lead clinicians to intensify outpatient diabetes medications at discharge, risking potential overtreatment when patients return home,” they wrote.

The retrospective cohort study focused on all veterans 65 years and older with diabetes not previously requiring insulin and who were hospitalized in a VA facility for common medical conditions between 2011 and 2013. The 16,178-member patient group had a mean age of 73 and were 98% men. Most, 53%, had a preadmission hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) level less than 7.0%, although 1,044 (6%) had an HbA1c level greater than 9.0%.

“Understanding the impact of hospitalization on outpatient diabetes control is particularly crucial for older adults, more than 25% of whom have diabetes,” according to the report. “Older adults are the most frequently hospitalized age group, and the balance of risks and benefits from strict blood glucose control may vary owing to limited life expectancy and elevated risks of hypoglycemia, polypharmacy and adverse drug events.”

Researchers focused on intensification of outpatient diabetes medications, which was defined as receiving a new or higher-dose medication at discharge than was being taken prior to hospitalization.

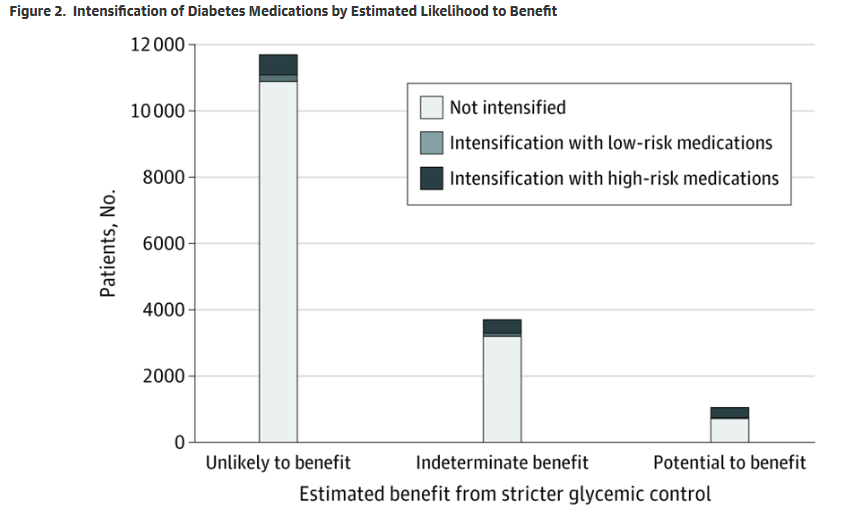

The study found that, overall, 1,626 patients (10%) were discharged with intensified diabetes medications—8% of them with intensified high-risk diabetes medications. That included 781 (5%) with new insulins and 557 (3%) with intensified sulfonylureas.

Yet, according to the researchers, nearly half, 49%, of patients receiving intensifications (791 of 1,626) were classified as being unlikely to benefit owing to limited life expectancy or already being at goal HbA1c, while 20% (329 of 1,626) were classified as having potential to benefit. The reminder had indeterminate benefit.

The study determined that both preadmission HbA1c level and inpatient blood glucose recordings were associated with discharge with intensified diabetes medications. In fact, among patients with a preadmission HbA1c level less than 7.0%, the predicted probability of receiving an intensification was 4% (95% CI, 3%-4%) for patients without elevated inpatient blood glucose levels, rising to 21% (95% CI, 15%-26%) for patients with severely elevated inpatient blood glucose levels.

The authors pointed out that, during hospitalization, it is not uncommon for outpatient medication regimens to be modified by inpatient clinicians. Changes generally are related to the condition that led to hospitalization—for example, receiving antiplatelets following an acute myocardial infarction. But, in some cases, inpatient monitoring leads to adjustments of medication regimens prescribed for chronic diseases, such as diabetes and hypertension, even though they are not directly connected to the primary condition for which the patient was hospitalized.

“Nonessential modification of chronic disease regimens during hospitalization may risk medication confusion and adverse drug events if patients are discharged with prescriptions for those modified regimens,” the authors cautioned.

Background information in the study cited prior research showing that intensifications of hypertension regimens also are common in hospitalized older adults and are driven by inpatient measurements. “Similar to blood pressure, blood glucose levels are monitored frequently in hospitalized patients with diabetes and elevated inpatient recordings may lead clinicians to discharge patients with prescriptions for intensified diabetes medications,” according to researchers. “Despite controversy over the benefit of strict inpatient glycemic control, the frequency of changes to outpatient diabetes regimens following hospitalization is unknown.”

It is not always a bad choice, the authors noted, and for patients with severely uncontrolled diabetes such as A1c levels higher than 9%, “medication intensification at discharge may improve hyperglycemia symptoms and set them on the path toward improved long-term glycemic control.”