BETHESDA, MD — Do socioeconomic disparities exist in the U.S. military healthcare system with ischemic stroke admissions? A new study says they do.

Researchers at the Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, MD, and the Carl R. Darnall Army Medical Center at Fort Hood, TX, reported that patients with higher military rank had “shorter hospitalization stays, higher costs and less in-hospital mortality in the military’s universal healthcare system.” Their study was published in the Journal of Neurological Science.1

According to lead author Matthew Blattner, MD, “rank as a marker for socioeconomic status has been validated in other studies but is an imperfect surrogate.” The study noted that enlisted personnel typically have lower socioeconomic status (SES) than officers, both before and after military service.

Using rank as a proxy for SES, the researchers sought to determine whether the socioeconomic disparities seen in the U.S. civilian healthcare system persisted in the MHS. Because the military offers care at no cost to servicemembers, the limitations to healthcare access that have been proposed as one explanation of disparities in the civilian setting are mitigated.

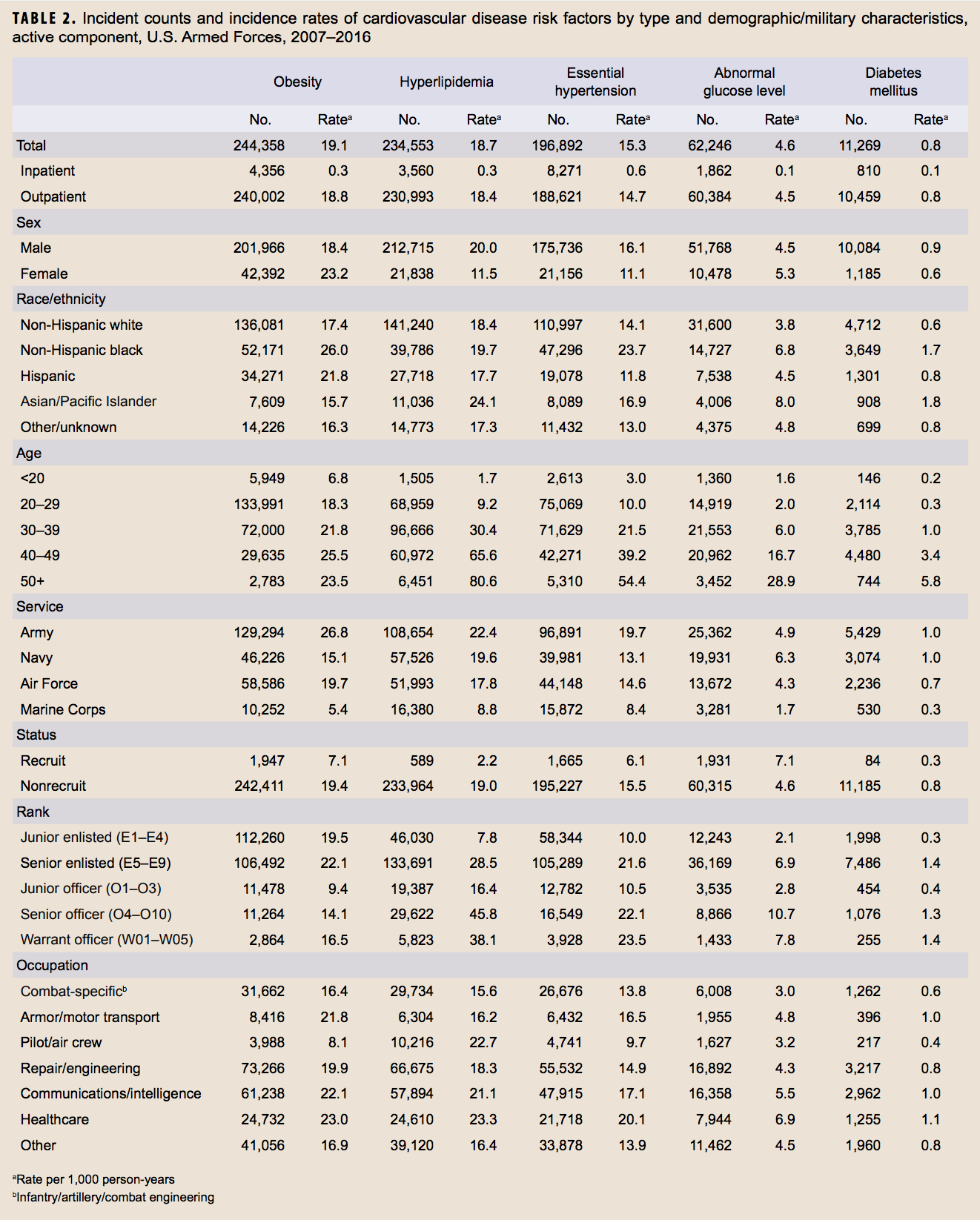

Using the MHS M2 database, the researchers identified 3,623 admissions to MHS treatment facilities with a primary diagnosis of ischemic stroke between 2010 and 2015. They analyzed the data to determine the effect of comorbidities such as diabetes, hypertension and atrial fibrillation, as well as demographics, hospital size, admitting service and time of admission. The MHS database did not track stroke severity.

The data included rank for 52.3% of admissions. For analysis, the team divided patients into four categories: junior enlisted, senior enlisted/warrant officers, junior officers and senior officers.

Age Differences

Senior enlisted/warrant officers had slightly higher rates of hypertension and diabetes than other groups, while senior officers had more atrial fibrillation. Most senior officers were more than 74 years old (51%), in contrast to the other groups which had very low rates of elderly—6% among junior enlisted, 29.6% in senior enlisted/warrant officers and 27.1% of junior officers.

While only 1.8% of patients received intravenous tissue plasminogen activator (tPA), its use was somewhat more frequent in officers and least common in senior enlisted/warrant officers, although the difference was not statistically significant, the study noted.

No junior officers and just one of the 100 admitted junior enlisted service members died of stroke during the study period. Senior enlisted/warrant officers had the highest mortality rate at 2.2%, and senior officers followed at 1.7%. Analysis after adjustments for comorbidities and demographics found, however, that senior officers were 62% less likely to die in the hospital following a stroke than the total population, “suggesting less severe stroke,” the authors said.

“Established health related risk factors such as hypertension, diabetes, and atrial fibrillation account for some of the observed effects of SES on outcomes after an ischemic stroke,” the researchers pointed out. The study found differences in those factors within the study cohort, with senior officers having lower rates of hypertension and diabetes.

Poor discharge destination settings, defined as anywhere other than the patient’s home, were least common among junior officers, at 11.9%, while junior enlisted and senior enlisted/warrant officers had rates of about 17%, and senior officers fell in the middle, at 14.7%. After adjustment, the odds of enlisted personnel being discharged to a destination other than home was 40% higher than the study average, “suggesting more severe strokes,” according to the authors.

Mean length of stay also showed significant variance, with the longest stays occurring among junior enlisted (5.84 days) and junior officers (4.6 days). Senior enlisted/warrant officers and senior officers had similar rates, 3.62 and 3.7, respectively.

While the records did not indicate what drove the differences in length of stay, Blattner offered some suggestions. “My best guess is that the strokes suffered by junior enlisted or junior officers occurred at a younger age, which often involves more extensive evaluation for the cause. It is also possible that the younger servicemembers were more likely to be active duty at the time of their stroke, so there are logistical military needs, such as reassignment to a medical unit that may have also contributed to their longer length of stay,” he told U.S. Medicine.

On average, hospitalization for stroke in this cohort cost $16,597, with the highest unadjusted cost among junior enlisted at $24,613, followed by junior officers ($18,742), senior officers ($15,734) and then senior enlisted/warrant officers ($14,002). The adjusted cost of hospitalization provided a significantly different picture, with costs rising across the ranks and the highest spending among senior officers.

“I believe that this study illustrates that there may be discrepancies in stroke care in the military health system based on socioeconomic status,” Blattner said. He and his colleagues concluded that socioeconomic factors may have affected outcomes in less-direct ways.

“It is likely that lifestyle and other variables existing prior to hospitalization may play a role in observed disparities in outcomes that are correlated with military rank and ischemic stroke outcomes,” the study authors wrote. “These include patient recognition of stroke symptoms, local emergency medical service triage and transport to appropriate level of care and post-discharge support at home. We suggest that these aggregate characteristics of a population (SES group), including its healthy and unhealthy behaviors and habits play a large role in the differences seen among SES group.”

1Blattner M, Price J, Holtkamp MD. Socioeconomic class and universal healthcare: Analysis of stroke cost and outcomes in US military healthcare. J Neurol Sci. 2018 Mar 15;386:64-68.