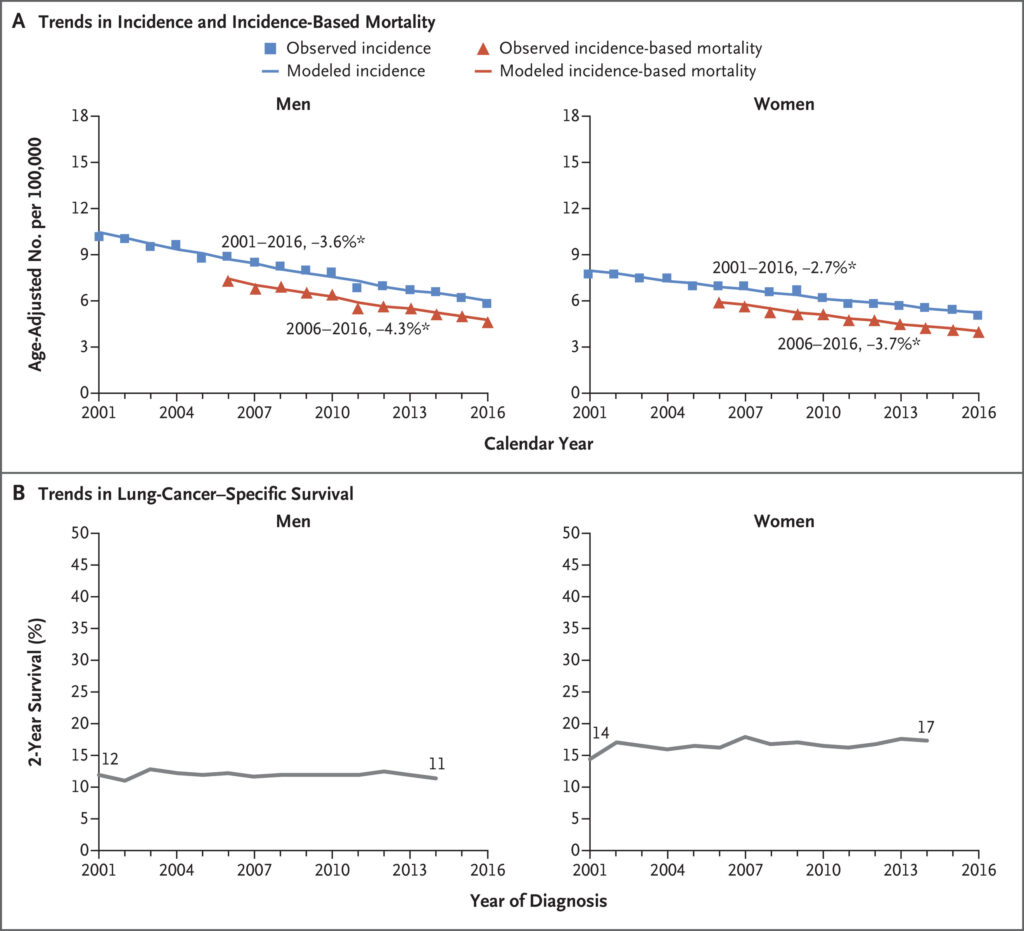

Click to Enlarge: Small-Cell Lung-Cancer (SCLC) Incidence, Incidence-Based Mortality, and Survival Trends among Men and Women. Panel A shows age-adjusted incidence (blue) and incidence-based mortality (red) for the SCLC subtype among men and women. Incidence was adjusted for reporting delays. The line segments of each curve were selected with the Join point program, and the percentage associated with each line represents the annual percentage change during the indicated range of years. Asterisks indicate annual percentage changes that are significantly different from zero (P<0.05). Panel B shows 2-year lung-cancer–specific survival according to year of SCLC diagnosis among men and women. Results are shown for the SEER 18-registry database. The following ICD-O-3 histology codes were used to define the SCLC subtype: 8002 and 8041–8045. Source: New England Journal of Medicine

CLEVELAND — “The more things change, the more they stay the same” could be a tagline for small cell lung cancer (SCLC). In recent decades, the epidemiology of SCLC has shifted substantially, as have the understanding of the disease, screening options and the treatments available. The malignancy, however, remains both challenging and highly lethal.

Worldwide, SCLC now accounts for approximately 15% of all lung cancers, down from 25% with smoking as a well-established etiological factor in up to 90% of cases.1,2 Increased public awareness of the association between smoking and lung cancer over the last 50 years and dramatic drop in the number of smokers in most countries drove down incidence rates for all lung cancers, including SCLC.

Where the overall survival rate for non-small cell lung cancer improved faster than the incidence of the malignancy declined as a result of more effective therapies, SCLC mortality declined in tandem with its incidence, while survival remained both dismal and largely unchanged.3

Still, the overall decrease in SCLC incidence is encouraging, though the impact varies significantly across demographics. Where males historically accounted for two-thirds of SCLC cases globally and three-quarters in the U.S., today they represent less than half, though what has driven the change is unclear. Further, while the cancer typically occurs in individuals over age 60, an increasing number of women under the age of 50 have been diagnosed with SCLC in the last two decades.4

Advances in Genetic and Molecular Pathology

A comprehensive understanding of SCLC’s genetic landscape has emerged only recently, thanks to next-generation sequencing (NGS) technologies. While historically limited by scarce tissue samples due to the aggressive nature of SCLC and the tendency toward small biopsy specimens, recent studies have identified characteristic mutations in genes involved in cell cycle regulation, DNA repair and apoptosis.

The most frequently mutated genes in SCLC are TP53 and RB1, present in nearly all cases. The loss of function in these tumor suppressor genes is a hallmark of SCLC, underpinning the cancer’s propensity for rapid proliferation and early metastasis. Additionally, aberrations in MYC family genes, including MYC, MYCL and MYCN, are observed in certain subsets of SCLC and are associated with particularly aggressive disease courses.5 These findings suggest a heterogeneous SCLC landscape, with distinct genetic subtypes that may eventually guide individualized therapeutic approaches.

Beyond driver mutations, recent research also has elucidated the role of epigenetic changes in SCLC pathogenesis. Histone modifications and aberrant methylation patterns have been implicated in SCLC, impacting gene-expression profiles and contributing to chemotherapy resistance.6

Improved Screening and Early Detection Strategies

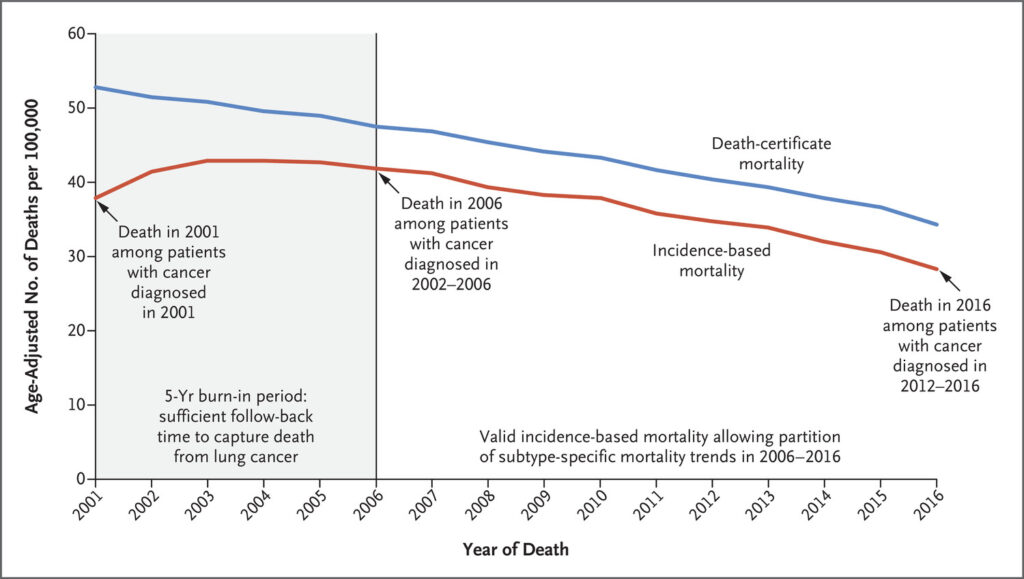

Click to Enlarge: Mortality Estimates Based on Data from Death Certificates and on Incidence among Patients with Lung or Bronchus Cancer.

Shown are the estimates of mortality from lung and bronchus cancer based on data from death certificates (blue line) and the corresponding estimates of mortality based on incidence (red line). In the area to the left of the vertical line at calendar year 2006, the incidence-based mortality underestimates mortality from lung cancer. Results are shown for the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) 18-registry database, which includes the following registries: San Francisco, Connecticut, Detroit, Hawaii, Iowa, New Mexico, Seattle, Utah, Atlanta, San Jose–Monterey, Los Angeles, Alaska Native, Rural Georgia, California (excluding San Francisco, San Jose–Monterey, and Los Angeles), Kentucky, Louisiana, New Jersey, and Georgia (excluding Atlanta and Rural Georgia). For both measures of mortality, attribution to lung-cancer death is made when the cause of death on the death certificate is stated as lung and bronchus cancer (International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, code C34). Source: New England Journal of Medicine

The challenge of early SCLC detection is compounded by its aggressive progression and asymptomatic onset in initial stages. Low-dose computed tomography (LDCT) has been a breakthrough for lung cancer screening in high-risk populations, reducing mortality in non-small cell lung cancer; however, its efficacy for SCLC is limited due to the rapid development and spread of SCLC lesions.7

Emerging technologies, such as liquid biopsies, offer promising alternatives for early SCLC detection. Liquid biopsies analyze circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) and other cancer-derived components in the bloodstream, providing a minimally invasive means of identifying tumor-specific mutations. In recent studies, ctDNA analysis has demonstrated high sensitivity and specificity for detecting SCLC-associated genetic alterations, even at early disease stages.8 These findings suggest that liquid biopsy may complement existing imaging modalities for more comprehensive lung cancer screening, especially in high-risk individuals where LDCT alone may not suffice.

In addition to ctDNA, biomarker panels that include microRNAs, protein signatures and autoantibodies are under investigation for their potential in SCLC screening. For example, microRNAs such as miR-375 and miR-92a have been shown to correlate with SCLC presence and progression, offering insight into tumor biology and possible disease monitoring.9

The landscape of SCLC is shifting due to changes in epidemiological trends, deeper insights into genetic and molecular pathogenesis, and innovations in screening technologies. While SCLC remains challenging to detect and treat, these advancements provide hope for improved outcomes through earlier diagnosis and potentially targeted therapies. As research progresses, continued integration of genetic profiling and novel biomarker-driven strategies into clinical practice may redefine the approach to SCLC, ultimately bridging gaps in survival for this aggressive cancer.

- Siegel RL, Miller KD, Wagle NS, Jemal A. Cancer Statistics, 2023. CA Cancer J Clin. 2023;73(1):17-48.

- Wang Q, Gümüş ZH, Colarossi C, Memeo L, Wang X, Kong CY, Boffetta P. SCLC: Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Genetic Susceptibility, Molecular Pathology, Screening, and Early Detection. J Thorac Oncol. 2023 Jan;18(1):31-46. doi: 10.1016/j.jtho.2022.10.002.

- Howlader N, Forjaz G, Mooradian MJ, Meza R, Kong CY, Cronin KA, Mariotto AB, Lowy DR, Feuer EJ. The Effect of Advances in Lung-Cancer Treatment on Population Mortality. N Engl J Med. 2020 Aug 13;383(7):640-649.

- Jemal A, Miller KD, Ma J, et al. Higher Lung Cancer Incidence in Young Women Than Young Men in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2018 May 24;378(21):1999-2009.

- George J, Lim JS, Jang SJ, et al. Comprehensive genomic profiles of small cell lung cancer. Nature. 2015;524(7563):47-53.

- Mollaoglu G, Guthrie MR, Bohm S, et al. MYC drives progression of small cell lung cancer to a variant neuroendocrine subtype with vulnerability to aurora kinase inhibition. Cancer Cell. 2017;31(2):270-285.

- Gay CM, Stewart CA, Park EM, et al. Patterns of transcription factor programs and immune pathway activation define four major subtypes of SCLC with distinct therapeutic vulnerabilities. Cancer Cell. 2021;39(3):346-360.e7.

- National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(5):395-409.

- Almodovar K, Iams WT, Meador CB, et al. Longitudinal ctDNA analysis correlates with relapse in SCLC patients receiving chemotherapy. Nat Commun. 2018;9(1):311.

- Wang Z, Chen Y, Zhang C, et al. A panel of microRNAs as a new biomarker for early detection of SCLC. Int J Cancer. 2015;136(1)