Click to Enlarge: *Adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, deprivation index, smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity, fresh fruit intake, body mass index, any indication of PPIs (gastroesophageal reflux disease [GERD], peptic ulcer, upper gastrointestinal bleeding), comorbidities (hypertension, type 2 diabetes, renal failure, myocardial infarction, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD], asthma), medications (aspirin, non-aspirin non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs [NSAIDs, ibuprofen], histamine 2 receptor antagonists (H2RAs), cholesterol lowering medications), multivitamin use, and influenza vaccination (for influenza) or COVID-19 vaccination (for COVID-19-related outcomes). Source: eLife

The National Randomized Proton Pump Inhibitor De-prescribing Program at the VA is seeking to reduce the number of PPI prescriptions amid growing concerns regarding their long-term and inappropriate use. Reports have linked them with a wide range of adverse conditions, including potentially dangerous respiratory tract infections.

Several mechanisms have been proposed for the association between the use of PPIs and respiratory tract infections. “Since a low pH of gastric acid rapidly inactivates microorganisms, one critical issue is that reduced acidity induced by PPIs leads to the overgrowth of microorganisms, which can contribute to the development of infections in the respiratory tract through microaspiration,” wrote authors of new study in eLife examining the link between PPI use and influenza, pneumonia and COVID-19. While the association of PPIs with influenza is unexplored, their association with pneumonia or COVID-19 remains controversial, they said.

To better understand the association between PPI use and each of the three conditions, researchers, including Felix W. Leung, MD, a gastroenterologist with the Greater Los Angeles VA Medical Center, leveraged data from the UK Biobank, a large-scale biomedical database and research resource containing disidentified genetic, lifestyle and health information and biological samples from half a million UK participants. Their study included 160,923 eligible participants between the ages of 38 and 71 who had completed questionnaires on medication use, which included PPI or histamine-2 receptor antagonist (H2RA).1

The exposure of interest was regular use of PPIs, with “regular” defined as most days of the week for the previous 4 weeks. The primary outcomes of interest were influenza, pneumonia and COVID-19 infections. The secondary outcomes included other upper or lower respiratory infections, COVID-19 mortality, and COVID-19 severity.

The researchers used univariate and multivariable Cox proportional hazards regression models to assess the association between regular use of PPIs and the selected outcomes.

Their findings:

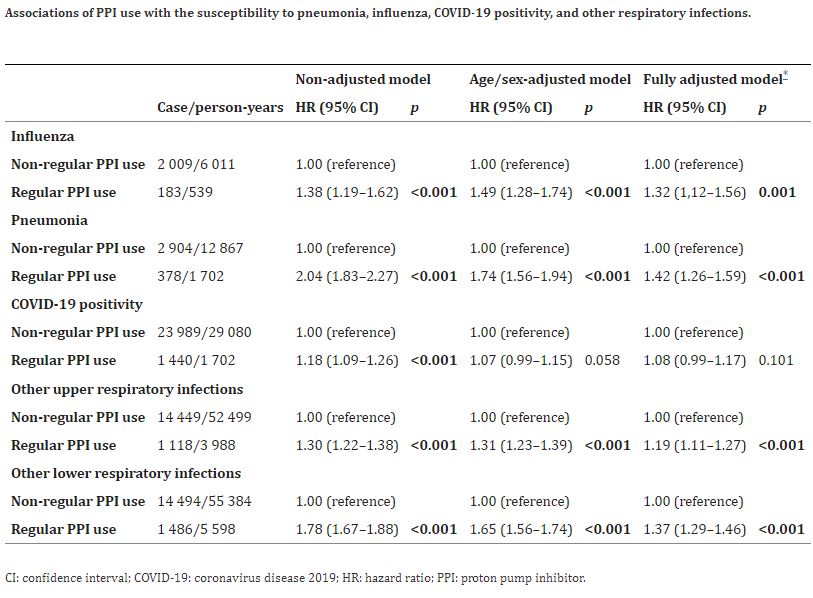

- Increased risks of developing influenza, pneumonia and other respiratory infections were identified in regular users of PPIs compared with nonregular users, and the risk remained raised after adjustments

- A 32% increased risk of developing influenza was observed among regular PPI users;

- Regular use of PPIs was associated with a 42% increased risk of developing pneumonia.

- Regular PPI users had lower event-free probabilities for influenza and pneumonia compared to those of nonusers.

- Initially, susceptibility to COVID-19 positivity was observed with an 18% increase in participants with regular use of PPIs. However, full adjustments for covariates—for example, age, sex, ethnicity. Alcohol consumption, smoking status, fresh fruit intake, multivitamin use and body mass index endured the association non-significant.

- For other upper and lower respiratory infections, the risks among regular PPI users were increased by 19% and 37%, respectively. In contrast, the risks of developing severe COVID-19 and mortality due to COVID-19 were significantly increased among PPI users compared to those among PPI nonusers.

- PPI users had lower event-free probabilities for COVID-19 severity and mortality, but not COVID-19 positivity compared to those of nonusers.

To further confirm the results and reduce the effect of confounding by indications, the researchers evaluated the risk of respiratory infections compared to the use of H2RAs, a less-potent class of acid-suppressant with indications similar to those of PPI. When compared to regular H2RA users, participants with regular use of PPIs also were associated with an increased risk of influenza, other upper respiratory infection and other lower respiratory infection. The associations with pneumonia COVID-19 infection, COVID-19 severity or COVID-19 mortality were not significant, however, the researchers reported.

Despite several strengths of the study—including the use of the updated large-sample data from the UK Biobank, exclusive inclusion of participants with valid records from primary care and adjustment for covariates which might contribute to indication or protopathic bias—it also has limitations. For example, information on dose and duration of PPI use, discrimination between prescription and over-the-counter use of PPIs, health-seeking behavior, different types of pneumonia and pneumococcus vaccination is currently not available from the UK Biobank, the researchers wrote. “Given that the PPI exposure was mainly assessed at the baseline recruitment, it was possible that a small proportion of PPI users was misclassified during the follow-up due to the medication discontinuation, which may result in an underestimation of potential risk.

However, the prevalent user design could underestimate the actual risks of PPI use for respiratory infections, which indicates the real effect might be stronger.”

“This study shows relatively weak associations between PPI use and respiratory infections, particularly influenza,” Jacob Kurlander, MD, MS, told U.S. Medicine. As a scientist at the VA Center for Clinical Management Research in Ann Arbor, MI, Kurlnder’s research has focused on the use of PPIs; however, he was not involved with this study.

“As with many of the observational studies that have shown links between PPIs and adverse health outcomes, we cannot draw strong conclusions about whether PPIs truly cause these respiratory infections or are simply statistically associated with them,” Kurlander said. “Nonetheless, this study is a good reminder that patients without an appropriate indication should be considered for medication withdrawal.”

- Zeng, R., Ma, Y., Zhang, L., Luo, D., et al. (2024). Associations of proton pump inhibitors with susceptibility to influenza, pneumonia, and COVID-19: Evidence from a large population-based cohort study. eLife, 13, RP94973. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.94973