WASHINGTON, DC — A recent audit of VA’s Medical Surgical Prime Vendor Program (MSPV) found that lack of oversight of the system, which is meant to save VA money by better leveraging the department’s buying power, is costing VA hundreds of millions a year.

The VA Office of the Inspector General (OIG) investigation revealed that medical facilities frequently do not purchase through the program, because the needed items are not on the MSPV product list; that staff defaults to buying from old vendors because facility order systems default to them; and that there is no easy way for facilities to lodge a complaint with the prime vendor about backlogged or unavailable products.

In 2022, the year from which auditors were drawing data, the MSPV contracts were held by three prime vendors. Those companies were responsible for stocking and distributing medical, surgical, dental and laboratory supplies on the VA product list, with each vendor having exclusive relationships with multiple medical facilities.

According to VHA performance metrics, facilities should purchase 90% of medical and surgical supplies through the MSVP to comply with its own regulations. In 2022, VA spent $865 million on supplies that were on the MSPV list. Some $353 million (41% of those purchases) were made through the open market, however.

The main reasons for this were because the product was not available through the prime vendor, despite it being on the list, or staff defaulting to buying from the open market without attempting the MSVP first. Auditors estimate that, had these purchases been made through the MSVP, the department could have saved approximately $35.5 million.

The savings per product can be considerable, especially when it comes to complex surgical equipment. The report details an incident in which staff at the VA Loma Linda, CA, Healthcare System attempted to buy a particular surgical product from the MSVP and found that it was on the list but not in stock. The healthcare system ended up paying $5,327.88 for the product on the open market. Had it been in stock through the MSVP, it would have cost $2,551.25.

Facilities also spent an additional $1.5 billion on products that were not on the MSPV list, suggesting that the vendor list, at that time, had less than 40% of the products VA facilities require.

Back-Order Problem Persists

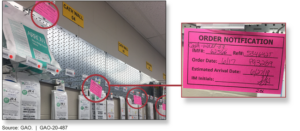

Facility logistics chiefs reported that back orders are a persistent program with the prime vendor program. If a facility’s inventory manager sees a product is on back order, meaning it cannot be filled, they go immediately to the open market.

However, because they do not at least attempt to place an order through the MSVP, it’s never logged in the system and has no impact on the prime vendor’s fill rate—the metric VA uses to determine a vendor’s performance, according to the OIG report.

This lack of accountability is most serious when it comes to core items that facilities order monthly. If one month an inventory manager discovers that an item is out of stock through the prime vendor, they might resort to the open market. When that happens, it creates a danger that the product will lose its core item status for future purchases, making it more likely the vendor will not stock it in sufficient quantities, the investigators pointed out.

When a facility does try to purchase a back-ordered product through the MSVP, the prime vendor is required to suggest other in-stock alternative products. Yet, this only happened about half of the time, and these substitutions are frequently unacceptable to clinicians, according to the OIG report.

The auditors found instances where a product was in stock and on the MSVP list, but because no facility had ever ordered it, it had never been assigned a purchase number. But because the process of assigning a number can take too long, facilities didn’t want to wait while one was created. This feedback loop resulted in 124,000 of approximately 480,000 open market transactions being for listed items that simply did not yet have a number assigned.

The product list changes monthly, and sometimes the swings in the number of products listed can be in the thousands. According to an OIG survey, the majority of facility supply chiefs said that their staff spend between 5 and 24 hours a week on challenges related to product list changes.

Methods created for facility staff to document problems with the MSVP are haphazardly used, the OIG reported, with many staff members saying they prefer to work directly with the prime vendor to address an issue. Quarterly evaluation reports are supposed to be submitted by facilities on prime vendors’ performance, but that doesn’t always happen. Staff at some facilities told auditors that the reports are “an administrative exercise in which the contracting officer’s representatives arbitrarily noted the prime vendors’ performance was satisfactory, although the staff might have been facing difficulties.”

The MSVP program has been in a state of constant flux since it was created in 2010. In 2021, VA announced it would be abandoning its current MSVP system in favor of the one used by DoD. However, a ruling in federal claims court said the move violated federal law regarding VA procurement rules, putting a halt to the initiative.

Since then, VA has been working to transition to MSVP Gen Z, which is scheduled to be implemented this September. According to VA, the contract will include “increased deliveries, increased accuracy and validation of performance metrics, and additional formal procedures to enhance performance management.”