Among American Indians and Alaska Natives (AI/AN), melanoma rates were highest for males 55 years and older and people living in the Southern Plains and Pacific Coast regions, according to a report from the CDC. While older men were twice as likely to be diagnosed with melanoma, as women, the rates increased among females from 1999 to 2019. Public health officials called for early detection in vulnerable cohorts.

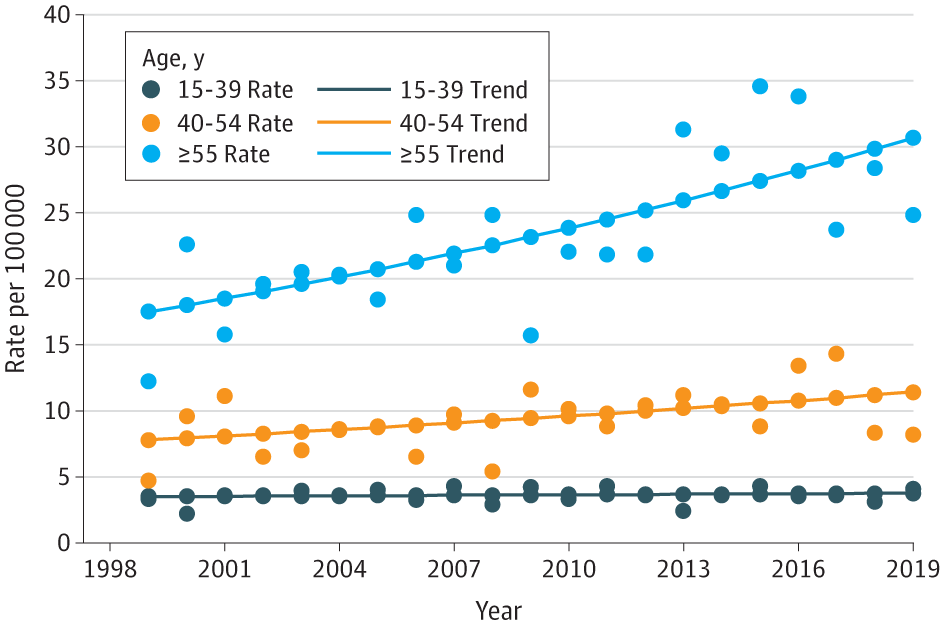

Click to Enlarge: Trends in Melanoma Incidence by Age Group for American Indian and Alaska Native Populations in Purchased/Referred Care Delivery Areas, 1999-2019 a. Source: National Program of Cancer Registries (NPCR) and Surveillance – Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) SEER*Stat Database: US Cancer Statistics American Indian and Alaska Native Incidence Analytic Database, 1998 to 2019. US Department of Health and Human Services–US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Released June 2022 based on the 2021 submission.

a. American Indian and Alaska Native race is reported by NPCR and SEER registries or through linkage with the Indian Health Service patient registration database. Includes only American Indian and Alaska Native of non-Hispanic origin.

ATLANTA — Non-Hispanic American Indian/ Alaskan Native (AI/AN) people have the second-highest rate of melanoma in the United States after non-Hispanic white people. Yet, due in part to the relatively small size of the population, very few studies have been conducted to understand the prevalence and patterns of melanoma in this group.

A new comprehensive study by researchers at the national Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and American Indian Cancer Foundation reveals some concerning trends, pointing to areas where further research and perhaps public health efforts are needed.1

Using the U.S. Cancer Statistics AI/AN Incidence Analytic Database, the researchers examined regional differences in melanoma incidence rates by age, sex and stage at diagnosis. The database, which is linked with Indian Health Service administrative databases, enabled the researchers to restrict data to people who reside in the Purchased/Referred Care [PRC] Delivery Areas and thereby reduced racial misclassification, said Julie Townsend, MS, an epidemiologist with the Division of Cancer Prevention and Control at CDC and lead author of the study.

Conducted over the 1999-2019 time period, the analysis was limited to people who were at least 15 years old and diagnosed with invasive cutaneous melanoma, said Townsend. “We calculated proportions; we produced age-adjusted incidence rates. We did it by group, by sex, by age at diagnosis,” she told U.S. Medicine. “We also looked at histological subtype.”

In addition, the researchers looked at where on the body melanoma was located, as well as where the patients themselves were located. They analyzed rates by poverty level in the county of residence and whether the county was rural, Townsend said. Regional and county rates were subdivided by age group, sex and stage at diagnosis.

In all, 2151 non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native people—1130 male, 1021 female—received a diagnosis of incident melanoma during the study period. Rates were higher among male than female individuals and for people 55 and older compared to those aged 15 to 39. Rates were highest for males 55 years and older and people living in the Southern Plains and Pacific Coast regions, the researchers reported in JAMA Dermatology. The rates increased among females from 1999 to 2019.

Older Men at Most Risk

“We found that rates were highest in men who were 55 and older,” Townsend said. “Men in this age group were twice as likely to be diagnosed with melanoma as women. Fortunately, two-thirds of people were diagnosed with local stage melanoma, and those tend to be melanomas that are easier to treat,” she said. In a bit of good news, incidence rate decreased overall, although rates increased for regional/distant stage tumors—a finding that “would want to warrant some additional research to understand,” she said. “We typically don’t see that in other analyses, so that was a surprise.”

Townsend said the findings underscore the importance of early detection and appropriate dermatologic care—“to make sure that people who need dermatologic care receive it in a timely and efficient manner.”

But access to that care and other specialty care services may be limited among American Indian/Alaska Native people who rely on the IHS system for healthcare, Townsend and her colleagues wrote.

“Healthcare for American Indian/Alaska Native people has been historically underfunded, and access to dermatology services may be limited due to priority for referrals that need immediate attention.”

Townsend added that “there probably needs to be some innovation [to ensure efficient care] in a setting where clinicians are busy managing other people’s chronic health conditions. So kind of getting that message that maybe some innovation is needed.”

In the meantime, the best advice for clinicians treating any patient is to evaluate any lesion that follows the ABCDEs (asymmetry, border, color, diameter, evolving) of melanoma. “Regardless of ethnicity, that’s a good starting point,” she said. “Any changes to skin, such as a new growth, a sore that doesn’t heal or a change in an old growth they need follow up”.

Likewise, she said, patients should let their clinicians know whether they have a history of skin cancer and, if they find something worrisome, to report it.

- Townsend JS, Melkonian SC, Jim MA, Holman DM, Buffalo M, Julian AK. Melanoma Incidence Rates Among Non-Hispanic American Indian/Alaska Native Individuals, 1999-2019. JAMA Dermatol. 2024 Feb 1;160(2):148-155. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.5226. PMID: 38150212; PMCID: PMC10753438.