Patients Struggle with Ill Health, Demanding Care Regimens

Diabetes, which can cause numerous adverse issues and shorten life, often requires chronic and demanding self-management. Many patients suffer emotionally because of that. VA clinicians now are focusing on the problem of “diabetes distress” and developing new ways to measure and respond to it.

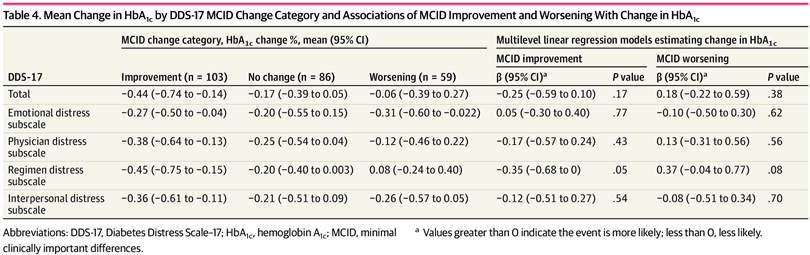

Click to Enlarge: Mean Change in HbA1c by DDS-17 MCID Change Category and Associations of MCID Improvement and Worsening With Change in HbA1c Source: JAMA Network Open

HOUSTON — The term “diabetes distress” is used to describe the emotional response to living with diabetes, a life-threatening illness that requires chronic and demanding self-management. It also takes into account other problems diabetes patients face, including lack of social support, a poor relationship with their physician or difficulty accessing healthcare.

Now, a new study has suggested values that are associated with clinically important improvements in diabetes distress, which could improve overall care for diabetes patients.

When treating diabetes patients, the healthcare field has lacked established minimal clinically important difference (MCID) values for the Diabetes Distress Scale—17 (DDS-17), a common measure of diabetes distress, the study authors explained.

The study published in JAMA Network Open was designed to “establish a distribution-based metric for MCID in the DDS-17 and its four subscale scores (interpersonal distress, physician distress, regimen distress and emotional distress),” according to the authors.1

The study authors were affiliated with the Houston Center for Innovations in Quality, Effectiveness and Safety (IQuESt) at the Michael E. DeBakey VAMC, the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, Baylor College of Medicine and University of Houston, all in Houston, and the University of Texas Medical Branch in Galveston.

In patients with Type 2 diabetes, reducing hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) levels has been found to lower morbidity and mortality. Since diabetes is a chronic condition, continued “reduction of HbA1c requires patient activation, commitment to treatment planning and self-management,” the report suggested.

Lifestyle changes that are required to manage diabetes “may carry an emotional burden that contributes to diabetes-associated distress, which refers to the worries, fears and threats arising from struggles with chronic diabetes care (i.e., management, complications and loss of function) and is associated with changes in HbA1c levels,” according to the article. “Patients with high distress have significantly higher HbA1c levels and are less likely to maintain blood glucose levels within the reference range,” the authors explained.

The DDS-17 is an established measure with 17 items to assess the level of distress in diabetes patients. “Higher DDS-17 scores are associated with poor lifestyle choices, self-management, self-efficacy, self-care, and adherence to recommended treatment regimens, while lower scores are associated with reductions in HbA1c,” the authors pointed out.

Previous DDS-17 validation studies have recommended distress thresholds, but the “cut points are limited by their inability to capture significant changes in DDS-17 scores that do not cross a cut point,” they added.

Smallest Meaningful Change

The researchers said they wanted to overcome the limitations of the DDS-17 and determine the clinical relevance of observed changes by calculating MCIDs, a “numerical score that shows the smallest meaningful change along the range of a continuous measure.”

In this study, the researchers used baseline and postintervention data from 248 participants in a randomized clinical trial comparing the Empowering Patients in Chronic Care (EPICC) intervention versus an enhanced form of usual care (EUC). The participants were adults with uncontrolled Type 2 diabetes (HbA1C level >8.0%) who received primary care in participating VA clinics across Illinois, Indiana and Texas. There were no differences in outcomes based on demographic factors, the researchers pointed out.

Participants in EPICC attended six group sessions led by healthcare professionals based on collaborative goal-setting theory. EUC included diabetes education, the authors explained.

The authors calculated distribution-based MCID values for the total DDS-17 and four DDS-17 subscales, using the standard error of measurement. They grouped baseline to postintervention changes in DDS-17 and its four subscale scores into three categories: improved, no change and worsened. The research team examined associations between treatment group and MCID change categories and whether improvement in HbA1C varied in association with MCID category.

“We calculated an MCID value of 0.25 for DDS-17, 0.38 for the emotional and interpersonal distress subscales, and 0.39 for the physician and regimen distress subscales,” Jack Banks, PhD, a researcher at Michael E. DeBakey VAMC, told U.S. Medicine. “Our findings suggest that MCID changes of 0.25 or greater on the DDS-17 are associated with clinically important improvements in diabetes distress.”

“In calculating the MCIDs for the DDS-17 and each of its subscales, we now have a measure with the ability to capture meaningful improvements or worsening of diabetes distress that are independent of a cut point,” said Banks, who also is a postdoctoral fellow in the School of Public Health at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

These findings could improve care for diabetes patients, he added.

“We hope that clinicians and patients will use the MCID values we calculated to assess response to treatments or interventions surrounding diabetes distress,” Banks said. “We also hope that researchers use these values to inform future research examining diabetes distress using the DDS-17 scale.”

Prior studies that have employed the DDS-17 have utilized a cut point of 2.0 as a dichotomous variable, with scores greater than or equal to 2.0 signifying the presence of moderate diabetes distress in participants, he explained.

A limitation of this cut point approach, however, is its inability to capture significant changes in DDS-17 scores that do not cross this 2.0 cut point, according to Banks, who added that the limitation can be overcome through the calculation of MCID values.

Distribution-based MCID values had not been established for the DDS-17, he advised, noting, “We wished to address this important research gap by calculating the MCIDs for the DDS-17 and each of its four subscales.”

- Banks J, Amspoker AB, Vaughan EM, Woodard L, Naik AD. Ascertainment of Minimal Clinically Important Differences in the Diabetes Distress Scale-17: A Secondary Analysis of a Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2023 Nov 1;6(11):e2342950. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.42950. PMID: 37966840; PMCID: PMC10652154.