Nov. 21, 2022-Photo: McDonough said, “I’m always impressed when I visit one of our Vet Centers and today was no different. Thank you, Lawton Vet Center Director Rochelle Mason and Deputy District Director Leticia Dreiling and staff for the great discussion today at the LawtonVetCenter. I got a lot of great feedback that I am taking back with me to DC”. (VA/Jennifer A. Roy)

WASHINGTON, DC — A recent VA Office of the Inspector General (OIG) audit has added more fuel to the argument around community care, finding that VA has provided little accountability over the third-party providers tasked with overseeing the department’s community care networks.

This lax oversight has led to an overall lack of accountability and resulted in the network being populated with physicians who do not actually treat veterans. In addition, VA staff are struggling to find enough providers to meet veterans’ needs.

Current and former VA leaders have expressed worry that the increasing costs of community care are eating into VA’s ability to properly resource its own facilities.

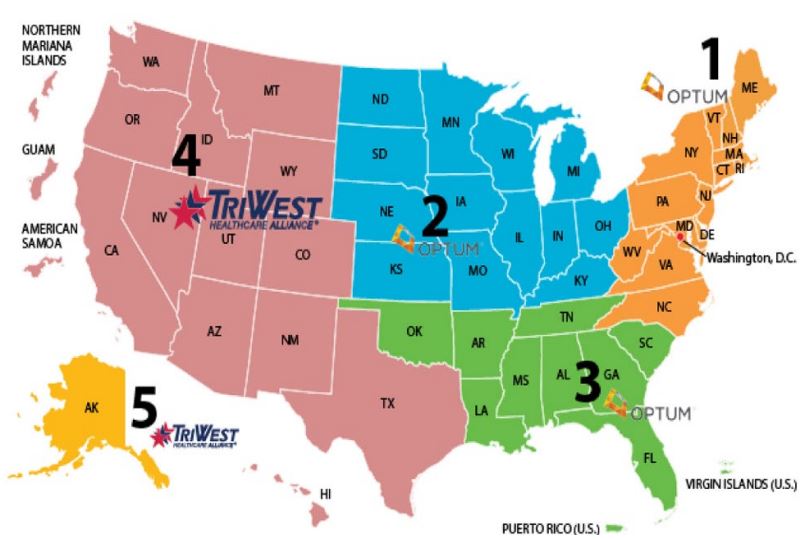

VA’s Community Care Network (CCN) is split into five regions, which are overseen by two third-party administrators (TPAs)—TriWest and Optum. The CCN was designed to make care coordination easier for VA, with the role of the TPAs being to sign up and vet community providers, ensure network adequacy and maintain and evaluate the network over time.

This original system was the result of the MISSION Act–legislation passed in 2018 that consolidated VA’s multiple community care systems, as well as opening the community care option up to many more veterans. If veterans live a prohibitive distance from a VA facility or cannot get an appointment with a VA provider in a certain amount of time, they can seek care from a CCN provider.

With legislation expanding who is eligible for outside care, an increase in users has contributed to the cost of community care skyrocketing in the last decade, going from $8 billion in 2014 to $31 billion in 2024. That represents about one-third of VA’s medical care budget.

Click to Enlarge: Five VA regional CCNs.

Source: “Community Care Network – Community Care (va.gov),” accessed August 22, 2022, va.gov

This has resulted in legislative conversation during the most recent VA budget cycle about the quality of community care and whether it truly allows veterans to receive quicker treatment.

The recent OIG audit took to task the CCN and VA’s Office of Integrated Veterans Care (IVC), which has been tasked with oversight of the third-party administrators.

“IVC did not hold TPAs accountable for implementing certain contract requirements designed to ensure facilities have sufficient access to a network of community providers who meet the needs of veterans,” the OIG report stated. “IVC’s ineffective oversight of TPA performance added to this lapse in contract accountability, which caused staff to struggle to convince TPAs to add community providers to their networks at the eight facilities the audit team visited.”

VA providers found that the CCN database included incorrect addresses and phone numbers for network physicians, as well as physicians that were not accepting veteran patients at all. When told about these inaccuracies by VA, the TPAs rarely revised them, since they required the doctor to contact them directly to make changes or request removal from the network.

The IVC also did not require the administrators to identify or detail the specialty procedures each provider offered. This can make finding a community provider who can meet a veterans’ specific needs challenging.

IVC leaders told auditors that the network database could not be updated or enhanced to include procedures.

“This system limitation prevents IVC and TPAs from being able to fully evaluate whether facilities had sufficient access to providers for all services and procedures,” the OIG auditors noted.

Not Enough Specialists

Facility staff reported frustration at the database’s limitations and by the unwillingness of TPAs to add more specialty providers to a network, especially after the first request. They would regularly be told by TPAs that they were mistaken and that the facility had enough specialists in the network, despite the mechanism for tracking providers being severely limited.

In response to the OIG’s findings, members of the Senate VA Committee sent a letter to VA Secretary Denis McDonough last month demanding a response from VA.

“Due to network inadequacies, VA medical center staff reported spending hours trying to find community providers who will accept veteran patients and cite this issue as one of the biggest roadblocks to the timely scheduling of appointments,” the letter stated. “Staff at many facilities created their own provider lists on spreadsheets to ensure they have accurate and complete information for community providers.”

The legislators noted that CCN contracts are up for rebid in 2026 and that VA needs to ensure that future contracts include language that will hold TPAs accountable.

Regarding the viability of the expansion of community care as a whole, McDonough said at a recent press conference that VA is evaluating its needs but isn’t ready to draw any conclusions yet.

“As we develop our FY25 budget and as we prepare the FY26 budget, we’re looking at these overall sets of questions to ensure that we have the staffing and the care provision,” he said. “We either purchase the care for the veterans in the community or we ensure that we have all the capacity in house … That gets more and more difficult when more and more veterans are referred into the community.”

He noted that in VISN 7, 70% of veterans qualify for community care because they live so far from a VA facility, but that private-sector facilities might be no closer.

“So when we refer them into the community, are we doing them a service?” McDonough asked. “Or are we just leaving the impression with them that we’re urging them to go into the community.”

He also said that VA is keeping an eye on DoD, which has recently stated its intent to move back to direct care after years of moving toward community care.

“There’s some frustration among [DoD] beneficiaries at the moment that there’s not sufficient care in the community where it’s needed. And now there’s frustration that there’s no sufficient care in the direct care system over there,” he said. “That’s also informing our ongoing efforts to make sure we’re budgeting in a sustainable way for veterans coming into VA.”

This fear is backed up by a recent report from the Veterans Healthcare Policy Institute, a nonprofit organization that studies active duty and veteran healthcare services. The report addresses the rising costs of community care, with its authors, including several former VA leaders, stating that “increased community care spending is a potential existential threat to the VA health system.”

“[Increased community care spending] threatens to materially erode the VA’s direct care system and create a potential unintended consequence of eliminating choice for the millions of veterans who prefer to use the VHA direct care system,” the report states.

This was particularly concerning, the authors noted, because the restructured community care network has achieved such mixed results in facilitating timely access for veterans.