What Doctors Can Do to Change That

SPRINGFIELD, MA — Lung cancer screening has the potential to save lives by catching lung cancer at an early stage with definitive treatment. But it also carries potential harms—including overdiagnosis, distress from false-positive results and complications of further testing. For some people, those downsides can outweigh any benefits.

SPRINGFIELD, MA — Lung cancer screening has the potential to save lives by catching lung cancer at an early stage with definitive treatment. But it also carries potential harms—including overdiagnosis, distress from false-positive results and complications of further testing. For some people, those downsides can outweigh any benefits.

While people who could benefit the most from lung cancer screening (LCS) often go unscreened, research has shown that, ironically, those who are least likely to benefit from screening are more likely to choose it. A new VA study, which examines the reasons for this, raises the need for physicians to rethink their conversations with frail patients.

Marginally Beneficial Screening

To better understand the decision-making process in patients with multiple chronic health conditions who would receive only marginal benefits from LCS, researchers interviewed 40 people with multimorbidity and limited life expectancy, as determined by high Care Assessment Need scores, which predict 1-year risk of hospitalization or death. Patients were recruited from 6 VHA facilities after discussing LCS with their clinician.1

In their interviews, patients shared several considerations, including their overall health and life goals, perceived benefits of LCS, trust in their clinician and the VA healthcare system and avoiding anticipated regret over declining LCS, that influenced their LCS decision-making, the authors stated.

When posed with hypothetical scenarios of limited benefit, patients emphasized the nonlongevity benefits of LCS—such as peace of mind, planning for the future—and generally did not consider their health status or life expectancy when making decisions regarding LCS.

“Most patients were unaware of possible additional evaluations or treatment of screen-detected findings, but when probed further, many expressed concerns about the potential need for multiple evaluations, referrals, or invasive procedures,” the authors wrote in Annals of Family Medicine.

Of the 40 patients interviewed, 26 had agreed to undergo VA LCS after discussing it with their clinician. While 14 veterans initially declined LCS, several were screened later, either within the VA system or elsewhere.

The Importance of Provider Influence

“I think the provider that a patient saw had a bigger influence on the patient’s decision to screen than on the patient’s characteristics themselves,” said lead author Eduardo Nunez, MD, of the VA’s Center for Healthcare Organization & Implementation.

Nunez said he thinks many patients probably don’t know that the harm of screening outweighs the benefit, explaining, “It’s hard for providers to discuss this concept of over-screening or that the harm may outweigh the benefits. So when providers bring up screening, the patients don’t really know, and they are likely to say go ahead and screen.”

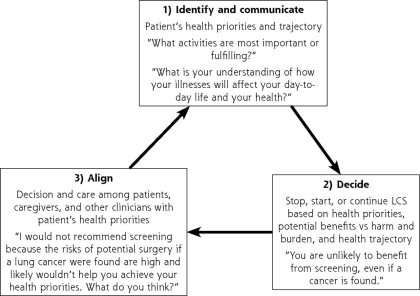

Nunez recommended that physicians follow guidance from the American Geriatrics Society on how to guide patients with multiple comorbidities on whether to undergo any screening test. “The idea is really to align the patient goals and values with the decision to screen, so if you are seeing someone who is having hard time walking or even changing their clothes you may talk to them about ‘what are your goals for the next few months or years or what would you like those goals to look like?’” he told U.S. Medicine. “You can then make a statement along the line of, ‘Screening is not in line with those goals, and we should focus on those goals—we should focus on being able to make sure you are breathing comfortably and aren’t short of breath when you are changing clothes.’”

“You don’t necessarily have to tell a patient ‘this screening isn’t recommended for you,’ and you shouldn’t tell a patient ‘you are going to pass away before we have benefit from this,’” Nunez continued. “It is more about how can you have a more in-depth conversation with them about what their goals are over the next months or years and aligning that with their general care plan so we are not doing unnecessary tests and especially not doing tests that will cause more harm.”

He said the other implication of his findings is the need for more guidelines on who could most benefit from screening. “Right now, it’s a gray zone,” Nunez said. “There is no professional society recommendation that says, if you think someone has more than 5 or 10 years of life expectancy, you should consider screening them. If they have less than 5 years, you should consider against screening them.”

The ideal, he said, would be a tool for providers that pops up in the electronic health record and, based on data pulled from the record, lets the provider know that “overall, this patient is likely to have net benefit from screening or overall this patient is likely to have net harm from screening,” he said. “Then the provider can guide the patient based on the tools for that specific patient.”

While lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in the U.S., only 5-10% of people have gotten screened, Nunez said. “Screening is effective, and we need multilevel strategies to increase the amount of people getting screened, especially those with net benefit, while guiding those who are less likely to benefit and more likely to experience a harm toward healthcare decisions that align with their goals.”

- Núñez, E. R., Bolton, R. E., Boudreau, J. H., Sliwinski, S. K., et al. (2024) “It Can’t Hurt!”: Why Many Patients With Limited Life Expectancy Decide to Accept Lung Cancer Screening. Annals of Family Medicine, 22(2), 95–102. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.3081