Adverse Effects From Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors

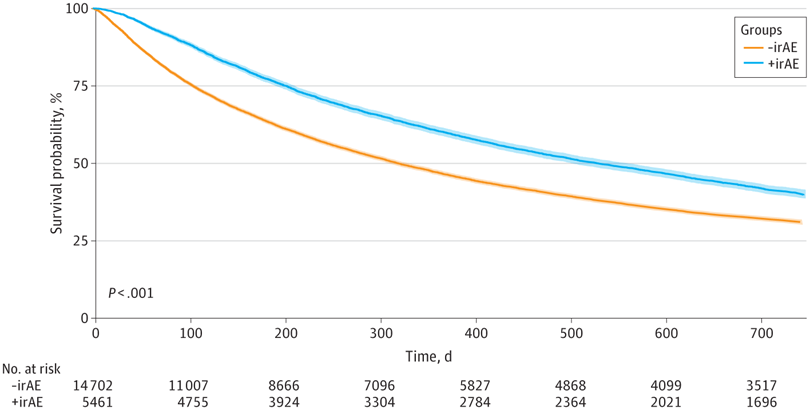

Click to Enlarge: Kaplan-Meier Curve Demonstrating Overall Survival in Patients With and Without Immune-Related Adverse Event (irAE)–Related Indications. Survival probability is shown for patients with (+irAE) and without (-irAE) International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision or International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision codes for irAEs. The median (IQR) OS was 10.5 (3.5-36.8) months for those without irAE codes and 17.4 (6.6-48.5) months for those with irAE codes (adjusted hazard ratio, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.81-0.84; P < .001). Source: JAMA Network Open

PORTLAND, OR — Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have played a crucial role in the field of immuno-oncology over the past decade, substantially improving the prognosis of different cancers. The drugs come with risks, however, including that of immune-related adverse events (irAEs)—autoimmune conditions that can affect any organ in the body due to the blockade of negative regulatory pathways that limit autoimmunity. These events most commonly involve the skin, gastrointestinal tract, endocrine glands, lungs or liver.

While irAEs can be managed with systemic steroids, there is concern that, due to steroids’ immunosuppressive properties, they might reduce or otherwise affect the therapeutic effect from these immunotherapies, said Reid F. Thompson, MD, PhD, associate professor of radiation medicine and biomedical engineering at Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) and affiliate investigator at the VA Portland Health Care System. A new study of veterans by Thompson and his colleagues helps allay these concerns and shows that the timing of steroids can impact survival.

To characterize how systemic steroids and steroid timing for irAEs are associated with survival in patients receiving ICI therapy, the researchers conducted a multicenter retrospective cohort study of veterans with an identifiable primary diagnosis of cancer receiving ICI between Jan. 1, 2010, and Dec. 31, 2021.1

The patients, who were identified through the VA’s Corporate Data Warehouse, were categorized into 3 cohorts: those receiving no systemic steroids, those receiving systemic steroids for irAEs and those receiving steroids for reasons other than irAEs. All eligible patients received 1 or more doses of an ICI (atezolizumab, avelumab, cemiplimab, durvalumab, ipilimumab, nivolumab or pembrolizumab). Eligible patients in the steroid group received at least 1 dose (intravenous, intramuscular or oral) of dexamethasone, hydrocortisone, methylprednisolone, prednisone or prednisolone. Steroid use at baseline for palliation or infusion prophylaxis or delivered as a single dose was deemed to be non-irAE associated. All other patterns of steroid use were assumed to be for irAEs.

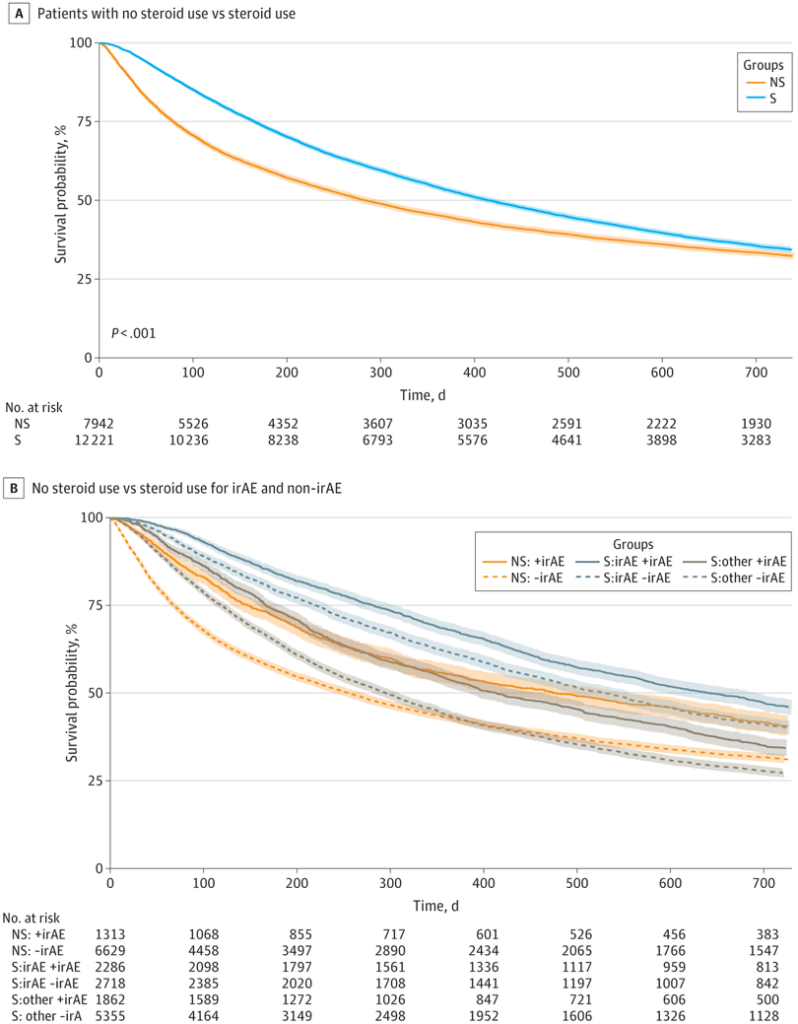

Click to Enlarge: Kaplan-Meier (KM) Curve Showing Association of Steroids With Overall Survival in the Full Veterans Cohort. Survival probability is shown for overall steroid (S) and nonsteroid (NS) groups (A) and for the following subgroups: patients in the nonsteroid group who nevertheless had an International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) or International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) codes for immune-related adverse events (irAEs; NS:+irAE), patients in the nonsteroid group who did not had an ICD-9 or ICD-10 code for irAEs (NS:-irAE), patients receiving steroids for irAEs who had an ICD-9 or ICD-10 code for irAEs (S:irAE+irAE), patients receiving steroids for irAEs who did not have had an ICD-9 or ICD-10 code for irAEs (S:irAE-irAE), patients receiving steroids for non–irAE reasons who nevertheless had an ICD-9 or ICD-10 code for irAEs (S:other+irAE), and patients receiving steroids for non–irAE reasons who did not have an ICD-9 or ICD-10 code for irAEs (S:other-irAE) (B) In Panel A, the adjusted hazard ratio was 0.88 (95% CI, 0.83-0.93; P < .001). The adjusted significance threshold was P < .003. Source: JAMA Network Open

Of the 20,163 veterans receiving ICI therapy, 12,221 received systemic steroids during ICI treatment, and 7,942 patients did not. Lung cancer, the most common cancer among the cohort, accounted for 54.5% of the primary cancers, followed by urinary tract cancers (14.7%) and melanoma (11.7%). In the cohort, ICIs were used in both the adjuvant and metastatic settings, with the steroid group having an overall higher rate of metastasis than the nonsteroid group, the researchers wrote in JAMA Network Open. More than a quarter (27.1%) of the entire cohort had new diagnoses suggestive of irAEs documented after initiation of ICI treatment. Among these patients, the majority received steroids.

The researchers divided the steroid cohort into 4 additional subgroups to assess timing of steroid administration in relation to ICI continuation status: early or late steroid use with ICI continuation or cessation. Early steroid use was defined as steroid administration less than 2 months after ICI initiation, whereas late steroid use was defined as steroid administration 2 or more months after ICI initiation. ICI status was defined as continuation or cessation of ICI treatment after steroid initiation.

The findings: “Patients with irAEs appeared to have greater survival benefit with immunotherapy than those without irAEs, and steroid treatment presumptively for irAE management did not appear to reduce this survival benefit,” said Thompson, adding that he was surprised how significantly and substantially the presence of irAE was associated with longer survival.

Earlier Versus Later Steroid Use

Among those who received steroids for irAEs, however, early steroid use (less than 2 months after ICI initiation) was associated with reduced relative survival benefit versus later steroid use, regardless of ICI continuation or cessation following steroid initiation.

Thompson cautioned that the research should not be interpreted to confer causality. “For instance, we found that immunotherapy cessation after early steroid use had a much worse survival versus continuation of immunotherapy after later initiation of steroid treatment; however, we cannot say this was causally related to continuation of immunotherapy,” he told U.S. Medicine. “It may be due, for instance, to high severity of high irAE in the early steroid-plus-immunotherapy cessation group, leading to reduced survival.”

He said considering the study’s retrospective nature and its limitation to a largely male veteran population, the results should be taken with a grain of salt. “Nonetheless,” he said, “this work should embolden clinicians to prescribe systemic steroids for irAE management where clinically appropriate, and should help provide supportive counseling regarding improved survival outcomes for patients who develop irAEs on immunotherapy.”

“To our knowledge, this is the largest cohort study to date investigating how systemic steroid therapy may be associated with OS in patients receiving ICIs, and it is the first to assess steroid timing relative to ICI continuation status following irAE development,” Thompson and his colleagues wrote.

They stated future studies are warranted to confirm and expand upon these findings in independent cohorts.

- Van Buren I, Madison C, Kohn A, Berry E, Kulkarni RP, Thompson RF. Survival Among Veterans Receiving Steroids for Immune-Related Adverse Events After Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy. JAMA Netw Open. 2023 Oct 2;6(10):e2340695. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.40695. PMID: 37906189; PMCID: PMC10618850.