Vaccines Were Received a Median of 13 Years Before

ATLANTA — The smallpox vaccine appeared to be effective in preventing mpox (formerly called monkeypox) in U.S. military personnel and veterans, even if received more than a decade previously, according to a new report.

The study was led by researchers from Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta and included researchers from the DoD, as well as VAMCs in Atlanta; Boston; Durham, NC; White River Junction, VT; Washington, DC; Cleveland and Hines, IL. It appeared in a letter to the editor in the New England Journal of Medicine.

“During the ongoing global outbreak of mpox (formerly called monkeypox), smallpox vaccines have been used to prevent infection and reduce the severity of disease in those at increased risk for infection,” the authors wrote. “However, the effectiveness of smallpox vaccines against mpox is unknown.”

To remedy that, the study team conducted a retrospective, test-negative case-control study among current and former U.S. military personnel to determine the effectiveness of smallpox vaccines against mpox.

At the time the study was conducted, more than 40,000 cases of monkeypox had occurred across the United States. Two vaccines were used for the prevention of monkeypox, ACAM2000 (2nd generation smallpox vaccine) and JYNNEOS (3rd generation smallpox vaccine).

“The most frequently cited data regarding the effectiveness of smallpox vaccines against monkeypox is from a retrospective analysis, published in 1988, which examined whether smallpox vaccination with Dryvax (1st generation smallpox vaccine) could also prevent mpox and reported an effectiveness of 85% against monkeypox among 338 patients in the Democratic Republic of Congo,” the researchers explained. Other vaccines weren’t tested, and it remained unclear how much the effectiveness of vaccination wanes over time or whether boosting previously vaccinated individuals would be beneficial, they added.

The authors noted that, from 2002 through 2017, more than 2.6 million U.S. military personnel had received smallpox vaccinations, either Dryvax, ACAM2000 or JYNNEOS vaccines, as part of their military deployment or occupational requirements.

The researchers aggregated two data sources—the DoD electronic laboratory data and the VA Corporate Data Warehouse—to identify eligible participants. They advised that logistic regression was used to calculate the association between a positive test result for orthopoxvirus species (which include smallpox, cowpox and mpox, among other viruses) and previous receipt of a smallpox vaccine.

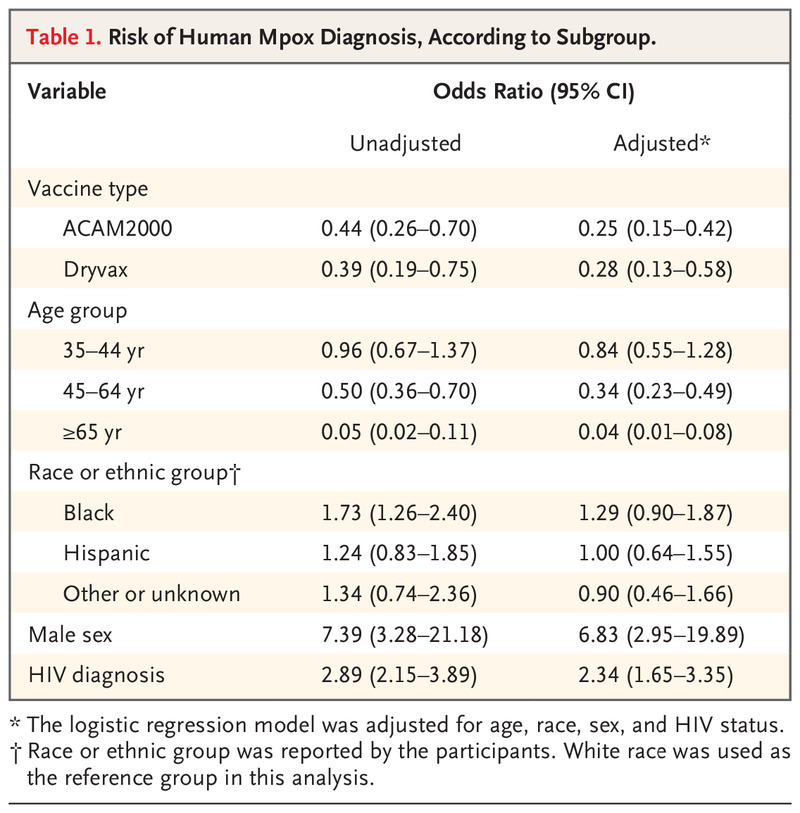

Potential confounders in the final model included age, race, sex and HIV status. For participants tested in the VA, the severity of disease was defined as admission to a hospital for mpox, but similar information was not available for participants outside a VA facility.

From July 1 to Oct. 31, 2022, the analysis included 1,014 current military personnel and veterans who had presented with a clinical syndrome resembling mpox and who had undergone testing for orthopoxvirus. Of those, 184 (18%) had a documented history of previous smallpox vaccination. Among the 293 participants (29%) who tested positive for orthopoxvirus, 10 (3%) had been vaccinated with Dryvax (a first-generation smallpox vaccine), and 20 (7%) had been vaccinated with ACAM2000 (a second-generation smallpox vaccine), they added.

The median time from receipt of the smallpox vaccination to the diagnosis of mpox was 13 years (interquartile range, 6 to 20), according to the report.

Vaccine Efficacy

“Participants who had received smallpox vaccination were less likely to test positive for mpox than those with no record of vaccination (odds ratio, 0.28; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.13 to 0.58 with Dryvax; odds ratio, 0.25; 95% CI, 0.15 to 0.42 with ACAM2000),” the researchers reported. “The estimated vaccine efficacy was 72% for Dryvax and 75% for ACAM2000.”

The study also pointed out that, among the participants who tested positive for orthopoxvirus, 121 (41%) had been diagnosed with HIV infection (odds ratio, 2.34; 95% CI, 1.65 to 3.35). Among veterans treated at the VA included in the study, 19 of 186 participants (10%) required hospitalization, but there were no deaths from mpox, and all the participants had an uneventful recovery.

“Previous vaccination at a median of 13 years earlier with either a first- or second-generation smallpox vaccine reduced the likelihood of testing positive for orthopoxvirus among current or former military personnel for whom vaccination data were available,” the study concluded.

“Our study found that, in military personnel who had a remote history of smallpox vaccination (i.e. vaccination between 2002-2017), their previous vaccination provided modest protection from mpox,” lead author Boghuma K. Titanji, MD, PhD, assistant professor of medicine at Emory University School of Medicine, told U.S. Medicine. “The estimated protection from 1st generation smallpox vaccines (Dryvaxx) was 72%, and for the 2nd generation smallpox vaccine ACAM2000 it was 75%.”

“The key message here is that previous smallpox vaccination offers modest protection against mpox. However, this protection wanes overtime, and protection is not lifelong. Therefore, individuals who are at risk for mpox may need updated vaccination to remain fully protected against this infection,” Titanji said.

The authors said their study was first and largest of its type—a real-world study estimating the effectiveness of older generation smallpox vaccines against mpox, including individuals with a more remote vaccination history.

They added that their research was limited by a small sample size and probably does not reflect the level of protection conferred by updated smallpox vaccines. “In contrast, our study evaluated the effectiveness of smallpox vaccination received between 2002-2017, which is within 20 years of the current outbreak,” the researchers wrote. “Comparatively, our effectiveness estimates are lower, suggesting differences in the level of protection conferred likely exist, based upon the vaccine formulation used or time since vaccination. Furthermore, the role of mucosal transmission in the current mpox outbreak may differentially modulate the effectiveness of vaccines administered by subcutaneous and intradermal routes.”

The study team went on to suggest that understanding how novel modes of transmission impact the efficacy of available vaccines will require more investigation. “The odds of testing positive for mpox decreased with increasing age in our cohort, independent of documented smallpox vaccination,” according to the report. “This mirrors patterns observed with other sexually transmissible infections such as gonorrhea, chlamydia, and syphilis and likely reflects changes in sexual behavior patterns that may occur with older age.”

“Because a cohort of U.S. military personnel had a history of vaccination against smallpox received during their time in the military for deployment purposes, this population presented a unique opportunity for us to be able to explore this important question,” Titanji said. “We confirmed observations that have been made by others that people with HIV have a higher-odds for mpox compared to individuals without HIV. This further highlights the need to prioritize this group with higher risk for mpox in vaccination campaigns against mpox.”

For healthcare professionals working to prevent mpox infection and reduce the severity of disease in those at increased risk for infection, the study authors noted that “smallpox vaccines remain an important tool to help control and prevent mpox.”

The researchers recommend that smallpox vaccines “should be combined with other preventive measures like behavior modification, testing and treatment of cases to ensure prompt containment of mpox outbreaks when these occur.”

In addition, the study team emphasized that protection against mpox conferred by previous smallpox vaccination “is not absolute, and vaccines need to be combined with other infection prevention strategies. While vaccine-induced immune responses following DryvaxÒ or ACAM2000Ò vaccination may provide durable protection against mpox, a subset of individuals, yet to be defined, might benefit from subsequent booster doses to optimize this protection.”

Currently, the national Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends a booster for individuals with continued exposure to orthopoxviruses two years after a primary series of JYNNEOSÒ vaccine and three-years after the single dose of 3 ACAM2000Ò(4), but the authors advised that the need for booster doses of vaccine and the timing of these for mpox remains to be determined.

“In our cohort, HIV diagnosis and male sex were associated with an increased likelihood for acquiring mpox.,” the study pointed out. “In the U.S., 98% of mpox cases are in men who have sex with men, and 38% have concomitant infection with HIV(5). Black and Hispanic ethnicities were associated with increased odds for mpox. Similar observations have been made in other studies, highlighting emerging disparities in the burden of mpox among people with HIV and individuals from racial and ethnic minority groups in the U.S.”

The authors also explained that Individuals diagnosed with HIV prior to separation from the military might have been less likely to be vaccinated because of their restriction from deployment and for safety reasons. “This introduces a potential indication bias and may over-estimate VE especially if this group would have had a lower VE if vaccinated,” they wrote. “However, the vast majority of veterans were diagnosed with HIV after separation, which would not have affected the decision to vaccinate”

- Titanji BK, Eick-Cost A, Partan ES, Epstein L, et. al. Effectiveness of Smallpox Vaccination to Prevent Mpox in Military Personnel. N Engl J Med. 2023 Sep 21;389(12):1147-1148. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2300805. PMID: 37733313; PMCID: PMC10559046.