DECATUR, GA — Traditionally treatment for chronic hepatitis C virus (HCV) infection has been reserved for people who have abstained from alcohol—in some cases for as long as 12 months—largely due to concerns about adherence to treatment protocols, which stemmed from experience with previously used interferon-based regimens.

While the VA—the largest provider of hepatitis C care in the United States—does not recommend withholding the newer direct-acting antiviral (DAA) treatments from patients due to alcohol use or alcohol use disorder, some clinicians continue to do so.

A new study published in JAMA Network Open suggested that might needlessly deprive those patients from treatment; it demonstrates that alcohol use does not lower the odds of achieving sustained virologic response (SVR) in patients receiving DAA therapy for chronic HCV infection.1

This retrospective cohort study led by Emily Cartwright, MD, an infectious disease specialist at the Atlanta VAMC in Decatur, GA, used data from the 1945 to 1965 VA Birth Cohort, which includes all individuals born between 1945 and 1965 who had at least one VA encounter on or after Oct. 1, 1999. Participants were those who were dispensed DAA therapy between Jan. 1, 2014, and June 30, 2018.

“This birth cohort was chosen because people born between 1945 and 1965 are known to have a 6-fold higher prevalence of HCV infection compared with all other age groups,” Cartwright and her colleagues wrote. “In addition, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended one-time HCV screening for these individuals during the time of study.”

Data analysis was completed in November 2020 with updated sensitivity analyses performed in 2023.

Based on responses to the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test-Consumption (AUDIT-C) questionnaire and International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision and International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision diagnoses for alcohol-use disorder (AUD), participants were classified into 5 mutually exclusive groups: abstinent without AUD, abstinent with AUD, lower-risk consumption, moderate-risk consumption and high-risk consumption or AUD. The researchers used lower-risk consumption as the referent group in all analyses.

The primary outcome was SVR, which was defined as undetectable HCV RNA for 12 weeks or longer after completion of DAA therapy.

Achieving Sustained Viral Response

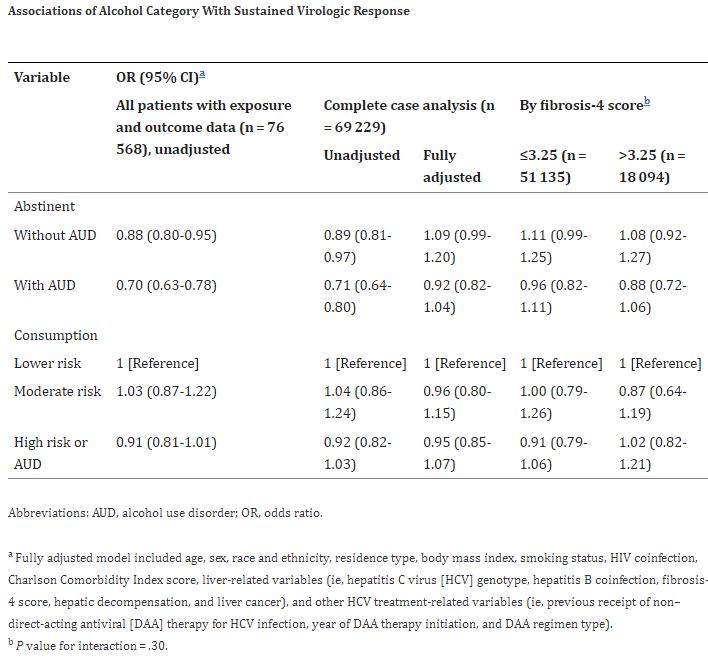

Among 69,229 patients who initiated DAA therapy, 65,355 (94.4%) achieved SVR. A total of 32,290 individuals (46.6%) were abstinent without AUD, 9,192 (13.3%) were abstinent with AUD, 13,415 (19.4%) had lower-risk consumption, 3,117 (4.5%) had moderate-risk consumption, and 11,215 (16.2%) had high-risk consumption or AUD. “We found no evidence that any level of alcohol use was associated with decreased odds of achieving SVR,” the authors wrote. “This finding did not differ by baseline stage of hepatic fibrosis.”

Moreover, the study population—of which the vast majority achieved SVR—was one of older individuals with multiple comorbidities, who are typically underrepresented in clinical trials. Furthermore, some patients were treated with older DAA regimens including sofosbuvir and ribavirin, which are less well tolerated and are associated with a lower percentage of patients achieving SVR, the researchers wrote. “Taken together, our findings support providing DAA therapy without regard to reported alcohol consumption or AUD.”

Although the study has some limitations—including the small percentage of women (3%) in the VA study population—the authors state that the VA population offered the ability to study the association of alcohol use with HCV treatment outcomes that would have been limited in other U.S. healthcare settings, given the current payment restrictions requiring alcohol abstinence before initiating DAA therapy.

The authors said their hope is that the findings will promote the use and coverage of DAA. They stated that a recent analysis of administrative claims and encounters in the U.S. found that only 23% of Medicaid, 28% of Medicare and 35% of private insurance recipients initiated DAA treatment within 1 year of HCV diagnosis. “Furthermore, that analysis found that Medicaid recipients were less likely to initiate DAA treatment if they resided in a state with Medicaid treatment restrictions including alcohol abstinence,” they wrote.

“Our findings suggest that DAA therapy should be provided and reimbursed despite alcohol consumption or history of AUD,” they concluded. “Restricting access to DAA therapy according to alcohol consumption or AUD creates an unnecessary barrier to patients accessing DAA therapy and challenges HCV elimination goals.”

- Cartwright EJ, Pierret C, Minassian C, Esserman DA, et al. . Alcohol Use and Sustained Virologic Response to Hepatitis C Virus Direct-Acting Antiviral Therapy. JAMA Netw Open. 2023 Sep 5;6(9):e2335715. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.35715. PMID: 37751206; PMCID: PMC10523171.

Table 1.

| Characteristic | Patients, No. (%) (N = 69 229) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abstinent | Consumption | ||||

| Without AUD (n = 32 290) | With AUD (n = 9192) | Lower risk (n = 13 415) | Moderate risk (n = 3117) | High risk or AUD (n = 11 215) | |

| Demographic characteristics | |||||

| Age, median (IQR), y | 63.3 (59.9-66.4) | 61.6 (58.4-65.0) | 63.0 (59.7-66.1) | 63.0 (59.8-66.1) | 61.8 (58.6-65.2) |

| 48-54 | 1440 (4.5) | 725 (7.9) | 662 (4.9) | 143 (4.6) | 793 (7.1) |

| 55-59 | 6787 (21.0) | 2635 (28.7) | 2982 (22.2) | 688 (22.1) | 3212 (28.6) |

| 60-64 | 12 418 (38.5) | 3497 (38.0) | 5233 (39.0) | 1248 (40.0) | 4290 (38.3) |

| 65-73 | 11 645 (36.1) | 2335 (25.4) | 4538 (33.8) | 1038 (33.3) | 2920 (26.0) |

| Sex | |||||

| Women | 1074 (3.3) | 251 (2.7) | 474 (3.5) | 49 (1.6) | 231 (2.1) |

| Men | 31 216 (96.7) | 8941 (97.3) | 12 941 (96.5) | 3068 (98.4) | 10 984 (97.9) |

| Race and ethnicity | |||||

| Hispanic | 1649 (5.1) | 450 (4.9) | 638 (4.8) | 112 (3.6) | 506 (4.5) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 12 702 (39.3) | 3738 (40.7) | 5608 (41.8) | 1117 (35.8) | 4929 (44.0) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 16 403 (50.8) | 4666 (50.8) | 6535 (48.7) | 1723 (55.3) | 5.327 (47.5) |

| Other or missinga | 1536 (4.8) | 338 (3.7) | 633 (4.7) | 165 (5.3) | 453 (4.0) |

| Residence type | |||||

| Rural | 8815 (27.3) | 2099 (22.8) | 3516 (26.2) | 964 (30.9) | 2695 (24.0) |

| Urban | 23 475 (72.7) | 7093 (77.2) | 9899 (73.8) | 2153 (69.1) | 8520 (76.0) |

| Clinical characteristics | |||||

| Body mass indexb | |||||

| Underweight (<18.5) | 467 (1.4) | 126 (1.4) | 208 (1.6) | 58 (1.9) | 243 (2.2) |

| Normal (18.5-24.9) | 8482 (26.3) | 2601 (28.3) | 3783 (28.2) | 1084 (34.8) | 3952 (35.2) |

| Overweight (25.0-29.9) | 12 244 (37.9) | 3515 (38.2) | 5232 (39.0) | 1186 (38.0) | 4208 (37.5) |

| Obese (≥30.0) | 11 097 (34.4) | 2950 (32.1) | 4192 (31.2) | 789 (25.3) | 2812 (25.1) |

| Smoking status | |||||

| Never | 5117 (15.8) | 795 (8.6) | 1840 (13.7) | 323 (10.4) | 779 (6.9) |

| Current | 18 686 (57.9) | 7053 (76.7) | 8831 (65.8) | 2305 (73.9) | 9345 (83.3) |

| Former | 8487 (26.3) | 1344 (14.6) | 2744 (20.5) | 489 (15.7) | 1091 (9.7) |

| HIV coinfection | 1072 (3.3) | 318 (3.5) | 409 (3.0) | 74 (2.4) | 344 (3.1) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index score | |||||

| 1 | 12 107 (37.5) | 3322 (36.1) | 6031 (45.0) | 1578 (50.6) | 4883 (43.5) |

| 2 | 8230 (25.5) | 2394 (26.0) | 3398 (25.3) | 834 (26.8) | 2976 (26.5) |

| 3 | 3273 (10.1) | 879 (9.6) | 1284 (9.6) | 265 (8.5) | 1072 (9.6) |

| 4 | 3313 (10.3) | 913 (9.9) | 1098 (8.2) | 195 (6.3) | 921 (8.2) |

| ≥5 | 5367 (16.6) | 1684 (18.3) | 1604 (12.0) | 245 (7.9) | 1363 (12.2) |

| Liver-related variables | |||||

| HCV genotype | |||||

| 1 | 27 342 (84.7) | 7727 (84.1) | 11 358 (84.7) | 2584 (82.9) | 9466 (84.4) |

| 2 | 2889 (8.9) | 824 (9.0) | 1242 (9.3) | 354 (11.4) | 1023 (9.1) |

| 3 | 1739 (5.4) | 560 (6.1) | 663 (4.9) | 153 (4.9) | 610 (5.4) |

| 4, 5, or 6 | 320 (1.0) | 81 (0.9) | 152 (1.1) | 26 (0.8) | 116 (1.0) |

| Hepatitis B coinfection | 581 (1.8) | 253 (2.8) | 185 (1.4) | 43 (1.4) | 246 (2.2) |

| Fibrosis-4 score | |||||

| <1.45 | 7402 (22.9) | 2162 (23.5) | 3400 (25.3) | 712 (22.8) | 2427 (21.6) |

| 1.45-3.25 | 16 489 (51.1) | 4353 (47.4) | 7137 (53.2) | 1641 (52.6) | 5412 (48.3) |

| >3.25 | 8399 (26.0) | 2677 (29.1) | 2878 (21.5) | 764 (24.5) | 3376 (30.1) |

| Hepatic decompensation | 1091 (3.4) | 640 (7.0) | 117 (0.9) | 14 (0.4) | 346 (3.1) |

| Liver cancer | 786 (2.4) | 363 (3.9) | 154 (1.1) | 34 (1.1) | 200 (1.8) |

| Treatment-related characteristics | |||||

| Previous non-DAA therapy for HCV infection | 6021 (18.6) | 1551 (16.9) | 1635 (12.2) | 298 (9.6) | 1127 (10.0) |

| Year of DAA therapy initiation | |||||

| 2014 | 3298 (10.2) | 978 (10.6) | 760 (5.7) | 116 (3.7) | 466 (4.2) |

| 2015 | 9995 (31.0) | 3111 (33.8) | 3556 (26.5) | 584 (18.7) | 2623 (23.4) |

| 2016 | 11 574 (35.8) | 3325 (36.2) | 5204 (38.8) | 1271 (40.8) | 4502 (40.1) |

| 2017 | 5932 (18.4) | 1400 (15.2) | 3099 (23.1) | 923 (29.6) | 2826 (25.2) |

| 2018 | 1491 (4.6) | 378 (4.1) | 796 (5.9) | 223 (7.2) | 798 (7.1) |

| DAA regimen type | |||||

| Sofosbuvir and ledipasvir | 18 526 (57.4) | 5569 (60.6) | 7954 (59.3) | 1867 (59.9) | 6805 (60.7) |

| Elbasvir and grazoprevir | 3387 (10.5) | 729 (7.9) | 1484 (11.1) | 361 (11.6) | 1234 (11.0) |

| Sofosbuvir and velpatasvir with or without voxilaprevir | 2270 (7.0) | 592 (6.4) | 1085 (8.1) | 341 (10.9) | 1000 (8.9) |

| Glecaprevir and pibrentasvir | 972 (3.0) | 234 (2.5) | 552 (4.1) | 127 (4.1) | 506 (4.5) |

| Paritaprevir, ritonavir, and ombitasvir with or without dasabuvir | 2747 (8.5) | 697 (7.6) | 1084 (8.1) | 199 (6.4) | 725 (6.5) |

| Sofosbuvir and daclatasvir | 389 (1.2) | 121 (1.3) | 148 (1.1) | 28 (0.9) | 124 (1.1) |

| Simeprevir and sofosbuvir | 1410 (4.4) | 427 (4.6) | 295 (2.2) | 29 (0.9) | 205 (1.8) |

| Sofosbuvir and ribavirin | 2589 (8.0) | 823 (9.0) | 813 (6.1) | 165 (5.3) | 616 (5.5) |

Abbreviations: AUD, alcohol use disorder; DAA, direct-acting antiviral; HCV, hepatitis C virus.