Click to Enlarge: Percentage of Mental Health Encounters Conducted via Video Telehealth (VTH) Over Time by Rurality and American Indian/Alaska Native Status Source: JAMA Network Open

SALT LAKE CITY — The American Indian/Alaskan Native population has traditionally experienced more serious health issues and barriers to healthcare compared to those of other races or ethnicities.

A new study published in JAMA Psychiatry shows that, for American Indian/Alaskan Native veterans, such disparities extend to their use of telehealth for mental health care and are worse for those living in rural areas.1

“Native Americans serve at one of the highest rates per capital of any ethnic minority group. As such, they disproportionately experience consequences of military service, including higher rates of posttraumatic stress disorder and other mental disorders,” said Jay Shore, MD, MPH, one of the study’s authors. “They’re also the most rural of our veterans, percentagewise.”

As a population specialist with the VA’s Office of Rural Health, one of Shore’s areas of focus has been on telehealth—“leveraging technologies to increase access to health,” Shore said. “Even within the VA—one of the earliest and largest providers of telehealth in the nation and the world—COVID was a game-changer because, out of necessity, how much videoconferencing had to occur,” he said. “Our team wanted to look at, if you have this expansion, what does it mean for populations like rural native veterans who had access challenges before the pandemic?”

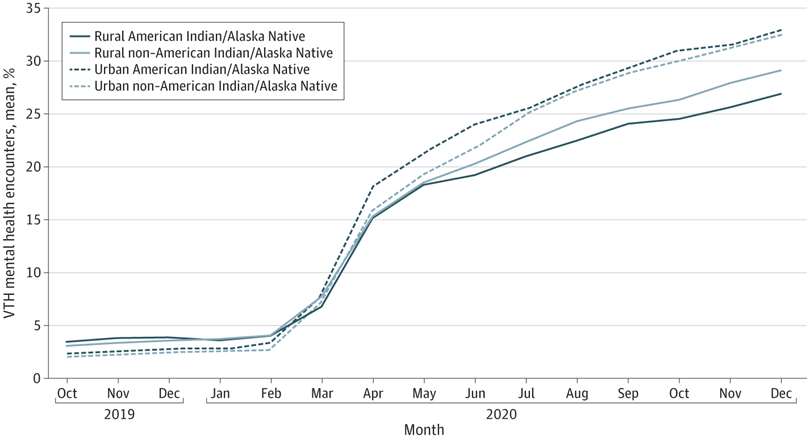

To examine differences in video telehealth (VTH) use for mental health care between American Indian/Alaska Native and non-American Indian/Alaska Native veterans by rurality and urbanicity—and how the boom in telemedicine use early in the pandemic affected those differences—researchers examined VHA administrative data on VTH use among a cohort of veterans who have had at least one outpatient mental health encounter from Oct. 1, 2019, to Feb. 29, 2020 (prepandemic), or April 1 to Dec. 31, 2020 (early pandemic).1

Of the 1,754,311-veteran cohort, 1.25% were American Indian/Alaska Native, and 98.75% were non-American Indian/Alaska Native, including Asian (1.41%), Black (24.96%), Hispanic and non-Hispanic White (71.17%), and Native Hawaiian/other Pacific Islander (1.20%). The mean age of all participants was 54.89 years and 85.21% were male.

Participants were designated as rural or urban based on geocoded patient location generated through a spatial intersection process.

Among American Indian/Alaska Natives, 8,425 (0.48% of the cohort) were designated as rural, while 13,452 (0.77%) were designated as urban. Among non-American Indian/Alaska Native participants, 509,447 (29.04%) were designated as rural and 1,222,987 (69.71% of the cohort) were designated as urban. Each veteran had one set of data for each month of the study: 5 prepandemic months and 9 early pandemic months.

Mixed models were used to examine rurality, American Indian/Alaska Native status, and the interaction between rurality and American Indian/Alaska Native status as factors associated with the percentage of MH care encounters that were VTH.

Increased Less in Native Populations

When controlling for age and self-reported gender, a greater percentage of mental health encounters were VTH in the early pandemic period compared with the prepandemic period. These differences varied by rurality and American Indian/Alaska Native status, the researchers reported.

Among American Indian/Alaska Native veterans, urban veterans had a mean increase in VTH use of 20.34 (0.38) percentage points (from 3.68% [0.33%] prepandemic to 24.02% [0.33%] during the early pandemic), whereas rural veterans had a mean increase of only 15.35 (0.49) percentage points (from 5.06% [0.41%] prepandemic to 20.41% [0.41%] during the early pandemic). The difference in differences between urban and rural American Indian/Alaska Native veterans was 4.99 percentage points.

Among non-American Indian/Alaska Native veterans, urban veterans had a mean increase of 12.97 (0.24) percentage points (from 2.86% [0.24%] prepandemic to 15.83% [0.24%] during the early pandemic), whereas rural veterans had a mean increase of only 11.31 (0.44) percentage points (from 4.47% [0.38%] prepandemic to 15.78% [0.38%] during the early pandemic).

The difference in differences between urban and rural non–American Indian/Alaska Native veterans was 1.66 percentage points, which is one-third the magnitude of the difference in differences for American Indian/Alaska Native veterans. “In other words,” the researchers wrote, “although urban veterans had a greater increase in the percentage of mental health visits that were VTH than did rural veterans, the rural-urban discrepancy was larger for American Indian/Alaska Native than for non-American Indian/Alaska Native veterans.”

When they investigated the association between a period of necessitated rapid virtualization of mental health care with VTH utilization for mental health care among American Indian/Alaska Native and non-American Indian/Alaska Native populations by rurality and urbanicity, they found that, although the use of VTH for mental health care increased in all groups, regardless of urban or rural status, American Indian/Alaska native populations had lower likelihood encounters than their non-American Indian/Alaska Native counterparts. Additionally, our results indicate that American Indian/Alaska Native veterans living in rural areas had fewer mental health VTH encounters than their urban counterparts.

The finding highlights the importance of understanding and addressing the diverse needs of the 574 federally recognized tribes, each with its own unique history and cultural practices, according to the authors. “Further research should investigate the nuances of the relationship between cultural factors and VTH uptake and use, with specific focus on the difference in health care-seeking behaviors between urban and rural populations as well as historical factors affecting VTH utilization for these groups, particularly the potential influence of health care practitioners from outside a community on mental health care-seeking behaviors,” they wrote.

Addressing Barriers to VTH Use

“Our results demonstrated a large difference in VTH use between rural and urban populations, especially among American Indian/Alaska Native veterans,” the authors wrote.

Efforts to increase access to telehealth services—which is a priority for the VA, Shore said—should address structural factors that hinder access. “I think across the population, there is a common theme,” he said. “Globally when you go to digital medicine there is the risk that you increase disparities because of challenges related to the social determinants of health that enable access to health care—things such as bandwidth, digital literacy, having the right equipment and having the resources to access health care.”

The study’s authors said understanding factors that affect uptake of VTH for mental health care when virtualization is necessitated by emergency situations—such as natural disaster, disease outbreak or security threat—is important to ensure progress toward more equitable care. “Future studies should examine potential differences in VTH use for this population based on gender or regional differences and ways the COVID-19 pandemic may have affected utilization,” they wrote. “Additional studies should be conducted to understand the importance of inequitable access to broadband internet, along with other social factors affecting health, such as geography, rurality, and socioeconomic status, for this population.”

- Kusters IS, Amspoker AB, Frosio K, Day SC, et. al. Rural-Urban Disparities in Video Telehealth Use During Rapid Mental Health Care Virtualization Among American Indian/Alaska Native Veterans. JAMA Psychiatry. 2023 Jul 26:e232285. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2023.2285. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 37494050; PMCID: PMC10372753.