Exposure to Agent Orange Also Linked to Condition

For veterans diagnosed with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis due to exposure to toxins during military service, the new PACT Act could literally be a lifesaver. The law assumes a service connection between the condition for certain military servicemembers. That is especially important because the prevalence of IPF more than doubled among veterans over the last decade or so.

SAN FRANCISCO — A new law that provides VA care for conditions presumed to be caused by exposure to burn pits and other toxins could be a game-changer for veterans with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis.

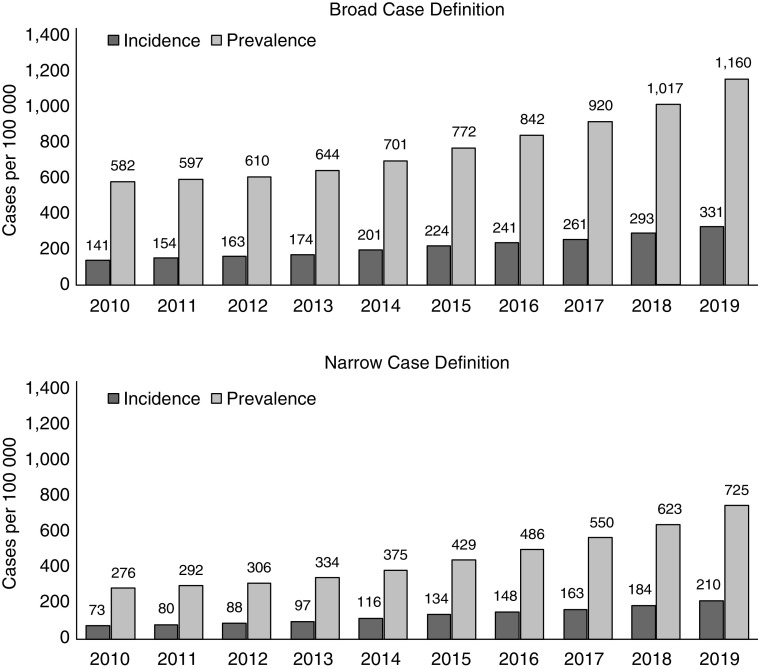

Click to Enlarge: Annual incidence and prevalence of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis among U.S. Veterans, 2010–2019. Source: Annals Of The American Thoracic Society

IPF is one of a group of diseases referred to as interstitial lung diseases, which involve inflammation and scarring of the lung. Patients with IPF typically present with an unproductive cough and shortness of breath. Over time, fibrosis progresses to a point where the lungs are unable to expand sufficiently to transport oxygen to the body’s organs and tissue.

While IPF is considered a rare disease, affecting an estimated 13 to 20 out of every 100,000 people, or between 0.10%-0.20%, worldwide, a recent study found that, among 10.7 million veterans who received care from the VHA between 2010 and 2019, 139,116 (1.26%) were diagnosed with IPF.

The PACT Act, which covers veterans from Vietnam through Iraq and Afghanistan, is the most significant expansion of benefits and services for toxic-exposed veterans in more than 30 years and addresses a broad spectrum of toxic exposures, according to the VA website.

The study—which was the first comprehensive epidemiologic analysis of IPF among the U.S. veteran population—further found that the incidence and prevalence of IPF among veterans has increased over the past decade. Between 2010 and 2019, the prevalence doubled (from 582 to 1,160 cases per 100,000 using the broad case definition and from 276 to 725 cases per 100,000 using the narrow case definition), and incidence more than doubled (from 141 to 331 cases per 100,000 person-years using the broad case definition and from 73 to 210 cases per 100,000 person-years using the narrow case definition.1

A more recent study published in The American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine pointed out the limited literature exploring the relationship between military exposures and IPF, however.

Some of the same researchers from San Francisco Veterans Affairs Healthcare and colleagues evaluated whether exposure to Agent Orange is associated with an increased risk of IPF among veterans. To do that, they used VHA data to identify male Vietnam veterans diagnosed with IPF between 2010 and 2019.

Noting that among 3.6 million male Vietnam veterans, 948,103 (26%) had presumptive Agent Orange exposure, the study team found that IPF occurred in 2.2% of veterans with Agent Orange exposure versus 1.9% without exposure (odds ratio, 1.14; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.12-1.16; P < 0.001).

“The relationship persisted after adjusting for known IPF risk factors (odds ratio, 1.08; 95% CI, 1.06-1.10; P < 0.001),” the study reported. “The attributable risk among exposed veterans was 7% (95% CI, 5.3-8.7%; P < 0.001). Numerically greater risk was observed when restricting the cohort to 1) Vietnam veterans who served in the army and 2) a more specific definition of IPF.”

The authors emphasized that, “after accounting for the competing risk of death, veterans with Agent Orange exposure were still more likely to develop IPF.”

The researchers concluded that presumptive Agent Orange exposure is associated with greater risk of IPF and called for future research to validate this association and investigate the biological mechanisms involved.

As its name implies, the cause of IPF in most cases is unknown. However, IPF and other respiratory problems have also been associated with exposure to burn pit emissions from open-air waste-burning and other airborne exposures in Gulf War era and post-9/11 veterans.

There is currently no cure for IPF, but treatment with anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic drugs may slow the progression of the disease. Supplemental oxygen therapy and pulmonary rehabilitation may improve activity levels and quality of life.

For many veterans diagnosed with IPF, treatment is now covered free of charge through the Sergeant First Class (SFC) Heath Robinson Honoring our Promise to Address Comprehensive Toxics (PACT) Act, which was signed into law last summer.

PACT Act Expands IPF Coverage

While some conditions caused by toxic exposures become evident quickly, others, including IPF, may take several years to cause symptoms. This lag time traditionally meant many veterans were outside their eligibility window to enroll in VA healthcare, and others struggled to prove a service connection because of the time that had lapsed.

The PACT Act makes it possible for more veterans to get treatment for IPF by:

- increasing the window of time they have to enroll in VA healthcare from 5 to 10 years following discharge for post-9/11 combat veterans

- establishing a 1-year open enrollment period

- adding IPF, along with 19 other “presumptive conditions,” meaning presumed to be caused by exposure to burn pits and other toxins.

In addition to IPF these presumptive conditions include 12 cancers (brain, gastrointestinal, glioblastoma, head, kidney, lymphatic, lymphoma, melanoma, neck, pancreatic, reproductive and respiratory) and respiratory conditions including asthma (diagnosed after service), chronic bronchitis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic rhinitis, chronic sinusitis, constrictive bronchiolitis or obliterative bronchiolitis, emphysema, granulomatous disease, interstitial lung disease, pleuritic and sarcoidosis.

Veterans with any of these conditions no longer need to prove their service caused the condition; they only need to meet the service requirements for the presumption to receive free care for their condition.

How Veterans Can Get Help

Under the PACT Act, veterans with IPF are eligible for care for up to 10 years from the date of their most recent discharge or separation if they:

- served in a theater of combat operations during a period of war after the Gulf War, or

- served in combat against a hostile force during a period of hostilities after Nov. 11, 1998

- were discharged or released on or after Oct. 1, 2013.

They also can enroll at any time during this period and get any care they need, but they may owe a co-pay for some care.

- Kaul B, Lee JS, Zhang N, Vittinghoff E, Sarmiento K, Collard HR, Whooley MA. Epidemiology of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis among U.S. Veterans, 2010-2019. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2022 Feb;19(2):196-203. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202103-295OC. PMID: 34314645; PMCID: PMC8867365.

- Kaul B, Lee JS, Glidden DV, Blanc PD, Zhang N, Collard HR, Whooley MA. Agent Orange Exposure and Risk of Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis among U.S. Veterans. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2022 Sep 15;206(6):750-757. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202112-2724OC. PMID: 35559726; PMCID: PMC9799114.