WASHINGTON, DC—The VA has committed to providing quality oncology care, with the establishment of the National Oncology Program and a system of excellence designed to spread best practices in cancer care to VA facilities around the country.

The teleoncology program brings specialists into consultation wherever needed and the precision oncology programs have promoted the molecular testing necessary for targeted treatment of cancers. It is no wonder the department has invested heavily in this field: the VA diagnoses 43,000 new cases of cancer each year.

The precision oncology programs at the VA have focused on solid cancers—prostate, lung, breast and gynecological malignancies, in particular. So far, specialized programs have not been established for blood cancers, many of which are presumptive conditions for veterans exposed to Agent Orange or benzene groundwater contamination at Camp LeJeune.

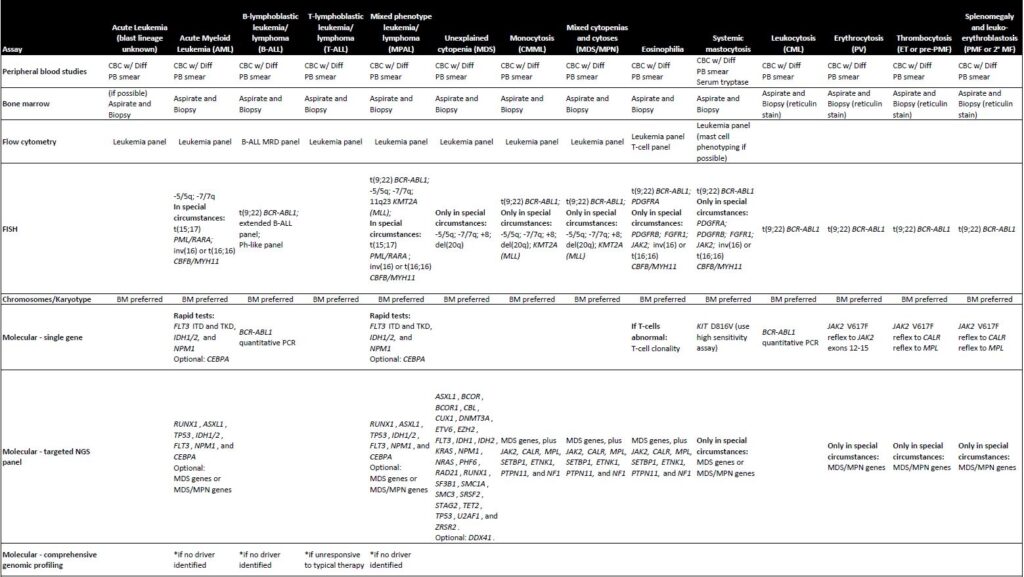

Recently, however, the VA National Oncology Program and the Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Program offices developed recommendations for advanced laboratory and molecular testing in connection with hematologic malignancies.1

“We aim to offer best practice for all VA providers who must decide the type of ancillary tests at the time of initial clinical presentation in order to gain prognostic information and guide therapy,” said the authors who included Jadee Neff, MD, PhD, Sara Ahmed, PhD, and Michael Kelley, MD, of the VA National Oncology Program; Claudio Mosse, MD, PhD, of the VA’s Pathology and Laboratory Medicine Program; and Jessica Wang-Rodriguez, MD, of the VA San Diego Healthcare System.

“The joint effort from VA Oncology and Pathology presents advanced testing algorithms in a variety of hematolymphoid malignancies as a systematic approach to hematopathology diagnosis, classification, as well as offering prognostic and therapeutic information,” they noted. “The recommendations across VA Healthcare would ensure standardized care for all VA patients with hematologic malignancy to benefit from the latest advances in precision medicine.”

The recommendations include a wide range of tests, including morphology, flow cytometry, immunohistochemistry and fluorescent in situ hybridization (FISH), karyotype, polymerase chain reaction (PCR), and next-generation sequencing (NGS). The sequencing may be the most challenging, though, it is essential for precision oncology.

For acute myeloid leukemia (AML), for instance, the guidelines recommend single gene rapid tests for FLT3 ITD and TKD, IDH1/2 and NPM1, with CEBPA optional. Targeted NGS panels should include RUNX1, ASXL1, TP53, IDH1/2, FLT3, NPM1 and CEBPA. MDS genes or MDS/MPN genes are considered optional.

Standardizing testing would improve therapy decision-making. A study of 3,638 veterans with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) found that only 19% had cytogenetic/FISH testing to detect the deletion of 17p, a strong negative prognostic marker important in selection of effective chemoimmunotherapy regimens.2

The Challenge

To that point, Kelley and colleagues at the VA Ann Arbor, MI, Healthcare System addressed some of the difficulties in undertaking genetic profiling of cancers in another study recently published in JCO Oncology Practice.3

The team of researchers investigated whether veterans and the general population had similar prevalence rates of potentially pathogenic germline variants (PPGVs) that require genetics referral for follow-up and germline sequencing and, if so, the impact of expanding access to genetics providers. The researchers noted that veterans face particular challenges including a “paucity of genetics providers, either at a veteran’s VA facility or nearby non-VA facilities.”

Germline sequencing identifies inherited or germline mutations, such as BRCA1/2 variants, which increase risk in many of the malignancies prioritized in the VA’s precision oncology programs including prostate, breast and ovarian cancers.

The JCO study team looked at rates of PPGVs in 208 veterans who received cancer care at the VA Ann Arbor Healthcare System and 20,014 veterans with data in the National Precision Oncology Program database whose tumors were profiled between 2015 and 2020. The Ann Arbor veterans had primary tumors from 20 different sites. The team “sought to determine how many veterans have PPGVs on the basis of tumor-only sequencing to specifically characterize the scope of the unmet need for cancer genetics services within the VA,” said first author Anthony Scott, MD, PhD, of the VA Ann Arbor, MI, Healthcare System and University of Michigan, and his colleagues.

The researchers found that 8.5% of the patients in the Ann Arbor cohort had PPGVs, many of whom would not have been referred for genetic counseling based on their type of tumor. On the national level, 6% of veterans with cancer had PPGVs. The range corresponds to that seen in the general population, emphasizing the need for inclusion of genetic analysis as a standard component of cancer care for veterans.

“These data point toward the need to expand genetics services for our veteran population,” said Scott and colleagues. “These services currently exist only at a handful of centers and funding may be limited for their provision as well.”

The JCO study focused on solid tumors, but the same need is likely present for hematological cancers as well. CML is unusual in its association with a somatic variant in a single gene. AML and other blood cancers have a germline component as well.

“The evidence for risk alleles in leukemia is still emerging,” Scott told U.S. Medicine. The “inherited monogenic risk for hematologic malignancies is only now starting to catch up with traditional hereditary cancer predisposition syndromes (breast/ovarian/pancreatic/colon cancers, among others), and only in select cases. However, I would assume that anything we find in the general population will be identified at the VA in a similar proportion as well.” Several recent studies have suggested that 15% to 20% of patients with AML have predisposing germline variants.

“One complicating factor we would encounter at the VA, which trends a little bit older than the general population, is enrichment for clonal hematopoiesis of indeterminate potential,” Scott added. “These are genetic mutations limited to a specific clone of lymphocytes that are not present in the rest of the body and tend to accumulate with age; whether or not they are clinically significant is still under research.”

- Neff JL, Moss CA, Wang-Rodriguez J, Ahmed S, Kelley M. Recommendation on Advanced Molecular Testing in Hematolymphoid Malignancies in the Veterans Population. Blood. 2021 Nov;138(S1):49

- Halwani AS, Burninghma Z, Rasmussen KM, et al. Cytogenetic and fluorescence in situ hybridization testing in veterans with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. JCO. 2017 May;35(s15):7526-7526.

- Scott A, Mohan A, Austin S, Amini E, Raupp S, Pannecouk B, Kelley MJ, Narla G, Ramnath N. Integrating Medical Genetics Into Precision Oncology Practice in the Veterans Health Administration: The Time Is Now. JCO Oncol Pract. 2022 Jun;18(6):e966-e973. doi: 10.1200/OP.21.00693. Epub 2022 Mar 8.