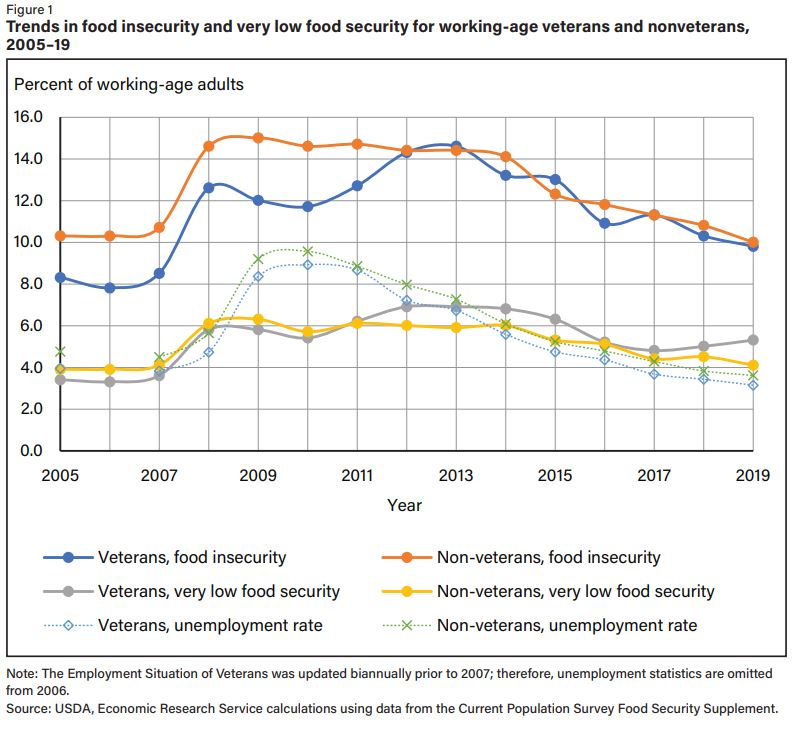

WASHINGTON, DC — Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, approximately 11% of veterans were living in a food-insecure household, and 5.3% lived in a household with very low food security, meaning that eating patterns were disrupted and food intake reduced.

That’s according to U.S. Department of Agriculture research—and officials assume the pandemic has only caused these numbers to increase.

In March, VA approved the creation of a National Food Security Program Office, which will focus on three key areas: collaboration with other agencies, data management and research. The office will extend and expand the already-existing Ensuring Veteran Food Security Workgroup, which has existed since 2016.

According to workgroup leaders, solving for food insecurity will have a direct impact on veterans’ health. People experiencing hunger face an increased chance of illness and may under use medication or delay medical care when faced with the choice of paying for food or paying for healthcare.

The challenge now for the new VA office and its partner agencies is determining the full extent of food insecurity among the veteran population and connecting those veterans and their families with existing programs designed to help feed them.

“Using the core tenet that food is medicine, we help move veterans from food insecurity to food security and eventually to nutrition security,” explained Christine Going, ED, MPA, RD, VA’s National Food Security Program Coordinator at a House VA Committee hearing held last month in San Diego.

Beginning in 2017, VA implemented a clinical reminder directing healthcare providers to screen veterans for food insecurity whenever they received care at a VA facility.

“We have instructed physicians to reach out to veterans who screened positive for food insecurity and connect them with food resources,” Going explained. “We’ve also updated community resource lists that might have been curtailed or created because of the pandemic.”

More Likely to Be Food Insecure

While existing data on food insecurity among veterans and active duty personnel is relatively scarce, researchers do know that veterans are 7.4% more likely to live in food insecure households than nonveterans. They also know that some veterans are more at risk than others. Women, veterans of color, those with a history of PTSD and military sexual trauma (MST), and those with a work-limiting disability are particularly susceptible to food insecurity.

“Veterans are at a higher risk of having a work-limiting disability. Poor mental health and work-limiting disabilities are associated with greater economic hardship and greater food insecurity,” explained Dr. Matthew Rabbit, PhD, a research economist with the USDA who co-authored a 2021 report on veteran food insecurity.

“Female veterans are more likely to live in food insecure households,” he added. “Health effects might account for this. Female veterans are at an increased risk of experiencing a work-limiting disability than comparable male veterans.”

Looking at data from 2015 to 2019, Rabbit found that 33.6% of veterans with work-limiting disabilities lived in food insecure households.

It’s also likely that the percentage of veterans with work-limiting disabilities will only grow over time, Rabbit noted. “As military medicine improves, younger veterans are more likely to survive what used to be mortal wounds in combat.”

USDA researchers also found that food insecurity was higher in veterans living in rural areas (13.9%) than those living in cities or the suburbs (10.6% and 8.7% respectively). Food insecurity also was higher among veterans with a lower education and among younger veterans compared to older ones.

Despite a higher rate of food insecurity, veterans are less likely to access food support programs than civilians. Asked why that might be, Rabbit said, “There’s no current research. But we can work with that as we get more resources.”

Food insecurity also extends to active duty servicemembers. A 2019 report released by the Military Family Advisory Network found that 15% of active duty servicemembers reported having trouble feeding their families, and 23% had children receiving free or reduced cost meals at school. Some service organizations point to the low pay for new servicemembers combined with a high rate of unemployment among military spouses (24% prior to the pandemic) as significant contributing factors.

However, there is evidence that the sudden absence of military infrastructure in a new veteran’s life can have a strong negative impact on food security. A 2015 study found that new veterans participated in the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) at a higher rate (7.1%) than active duty servicemembers (2%) and longtime veterans (6.5%).

These statistics will likely play a large part in the upcoming White House Conference on Hunger, Nutrition, and Health scheduled for September. The last such conference was held in 1969.