Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, of the VA St. Louis Healthcare System led earlier studies which shined light on serious cardiovascular conditions and mental health disorders that could arise in the weeks or months after initial COVID-19 infection. Source: VAntage Point blog March 3, 2022.

ST. LOUIS — Despite vaccinations, improved treatments and generally milder symptoms associated with omicron and its subvariants, COVID-19 continues to be a major public health concern and source of uncertainty. An estimated 10% to 30% of people who survive the acute infection live with lasting sequelae—known as long COVID—and increasing numbers of vaccinated people are being diagnosed with breakthrough infections. Whether people with breakthrough infections experience such post-acute sequelae has not been clear. But a new study of more than 13 million veterans offers a troubling answer—it does, although at a slightly reduced rate compared to those who are vaccinated.

In the study, published in Nature Medicine, researchers analyzed the de-identified medical records of more than 13 million veterans in VA national healthcare databases. They examined data of 113,474 unvaccinated COVID-19 patients and 33,940 vaccinated patients who had experienced COVID-19 breakthrough infections, all from Jan. 1 through Oct. 31, 2021.1

“Initially what we tried to determine is if people with breakthrough infections get long COVID at all, and what we found was that indeed they do,” said Ziyad Al-Aly, MD, a clinical epidemiologist at Washington University and chief of the Research and Development Service at VA St. Louis Health Care System. The next step, he said, was to ask whether vaccination reduces that risk at all. Comparing people with breakthrough infections to those who were unvaccinated, Al-Aly and his colleagues found that vaccination reduces the risk of long COVID, but only by 15%. “So there was some reduction, but it wasn’t huge,” he said.

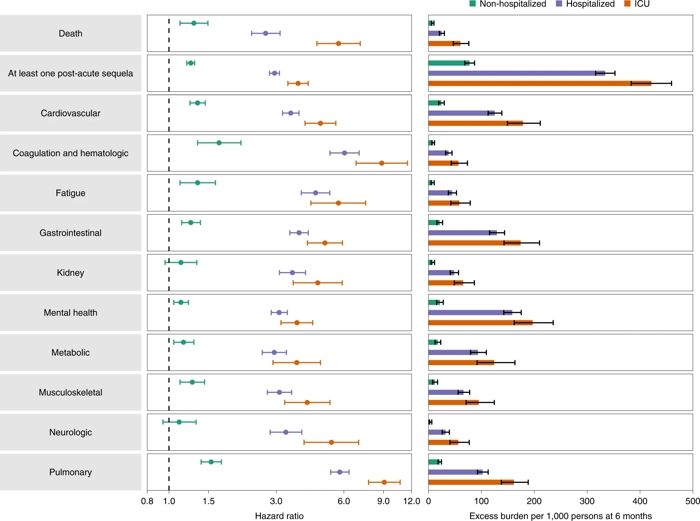

Click to Enlarge: Risk and 6-month excess burden of death, at least one post-acute sequela and post-acute sequelae by organ system are plotted by care setting of the acute phase of the disease (not hospitalized, hospitalized and admitted to ICU). Incident outcomes were assessed from 30 days after the positive SARS-CoV-2 test to the end of follow-up. Results are in comparison of BTI (non-hospitalized n = 30,273; hospitalized n = 3,667; admitted to ICU n = 811) to the contemporary control group with no record of a positive SARS-CoV-2 test (n = 4,983,491). Adjusted HRs (dots) and 95% CIs (error bars) are presented, as are estimated excess burden (bars) and 95% CIs (error bars). Burdens are presented per 1,000 persons at 6 months of follow-up. Source: Nature Medicine (2022)

Other findings of the study showed some greater benefits for vaccinated individuals, he said. “When you look deeper into the different results, the reduction was quite significant for two key areas—respiratory problems and coagulation disorders. Vaccination reduces risk of lung problems and also blood clotting by 50%.” The researchers noted that vaccination against SARS-CoV-2 reduced the risk of death by 34%.

Other findings of the study included:

- Long COVID risks were 17% higher among vaccinated immunocompromised people with breakthrough infections compared with previously healthy, vaccinated people who experienced breakthrough infections.

- Vaccinated patients who were hospitalized with breakthrough COVID-19 infections experienced 2.5 times the risk of death than people who were hospitalized with influenza. They also had a 27% higher risk of long COVID in the first 30 days after diagnosis, compared with 14,337 people who were hospitalized with seasonal influenza.

- Across the board, people who had breakthrough COVID-19 faced significantly higher risks of death and illnesses, such as heart and lung diseases, neurological conditions and kidney failure compared to long-term health outcomes with a pre-pandemic control group of more than 5.75 million people.

The study pointed out the limitations of current vaccines and reinforces the need to develop new vaccines and additional lines of defense, Al-Aly said.

“Current vaccines were designed about 2½ years ago and were never designed to reduce the risk of long COVID,” he said. “At that time, we didn’t even know that long COVID existed. The vaccines were not designed with that in mind. Now that we know long COVID is happening, even in vaccinated people, that means we cannot rely on vaccines as the sole line of defense.”

“We need to figure out if there are additional things we can do—any treatments that we need to discover, any treatments that we need to test, any new vaccines that we need to develop to try to reduce the risk of long COVID as much as possible.”

He continued, “COVID is not going away anytime soon. We have to figure out a way to live with it and not be hurt by it.”

- Al-Aly Z, Bowe B, Xie Y. Long COVID after breakthrough SARS-CoV-2 infection. Nat Med. 2022 May 25. doi: 10.1038/s41591-022-01840-0. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 35614233.