Alberto Ascherio, MD, DrPH, professor of epidemiology and nutrition at the Harvard Chan School of Public Health

BETHESDA, MD — Researchers with the Uniformed Services University of Health Sciences (USUHS) and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health appear to have solved one of the most perplexing mysteries in medicine: What causes multiple sclerosis (MS)?

While a number of drugs can slow progression of the disease, it remains incurable, making prevention a high priority.

A chronic inflammatory disease of the central nervous system that targets the myelin sheaths encasing neurons in the central nervous system, MS has long been considered an autoimmune disease of uncertain etiology. While some researchers had posited a relationship between the Epstein-Barr virus and MS, the virus’s near ubiquity—about 95% of adults have EBV antibodies—made showing a clear association challenging.

EBV, also known as human herpesvirus 4, causes infectious mononucleosis, though many people do not develop significant symptoms. The virus remains latent in the body after infection and may reactivate later in life, with some recent research indicating a link between EBV and myalgic encephalomyelitis or chronic fatigue syndrome.

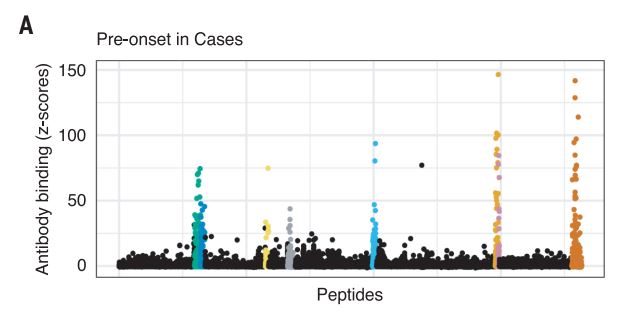

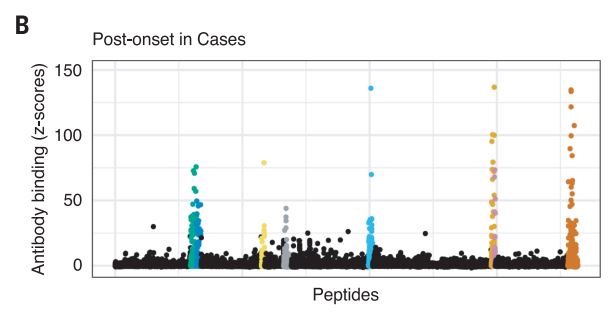

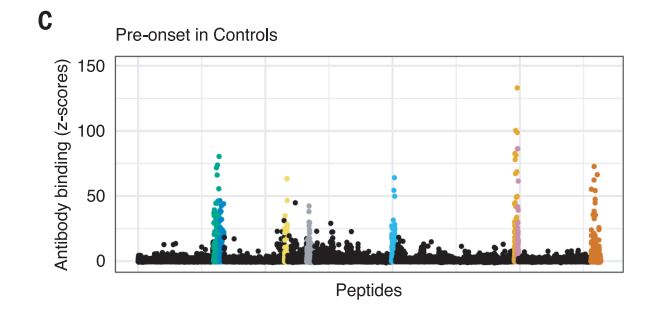

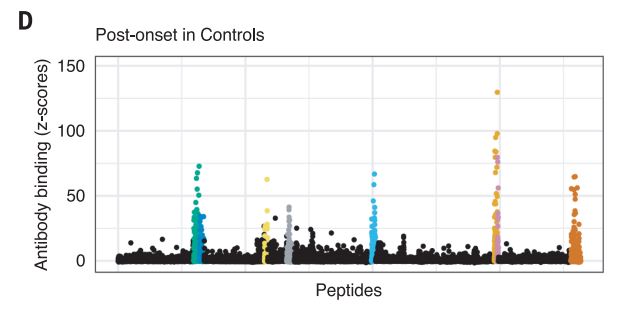

The Harvard/USUHS team demonstrated that infection with the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) likely causes multiple sclerosis by analyzing blood samples from 10 million U.S. servicemembers. The researchers found that EBV infection precedes the symptoms of MS and evidence of damage to the nervous system, and that infection exponentially increased the risk of developing the disease.1

“The hypothesis that EBV causes MS has been investigated by our group and others for several years, but this is the first study providing compelling evidence of causality,” said Alberto Ascherio, MD, DrPH, professor of epidemiology and nutrition at the Harvard Chan School of Public Health and senior author of the study. “This is a big step because it suggests that most MS cases could be prevented by stopping EBV infection, and that targeting EBV could lead to the discovery of a cure for MS.”

From the 10 million starting point, the team found 5.3% of servicemembers had not been infected with EBV at the time of the first blood sample taken as part of biennial testing by the military and archived in the Department of Defense Serum Repository. The researchers analyzed samples taken from this group over an average of 10 years. During that time, 955 developed MS. Only one individual developed MS, but remained EBV-negative when the last sample was taken.

The results provided unusual clarity. Servicemembers who never contracted the virus had a miniscule risk of developing MS. Servicemembers infected with EBV saw a more than 32-fold increase in the risk of the disease.

That does not mean that everyone who has ever had EBV has a high risk of MS. In fact, MS is a very rare complication. Certain factors double the risk of developing the disease following infection, including genetic susceptibility, vitamin D deficiency and cigarette smoking. Childhood obesity increases the risk 40% to 50%, Ascherio noted.

Two other aspects of the study further increase confidence in the results. The researchers included a control group, looking for any impact of another very common infectious agent, cytomegalovirus (CMV). They found no association between CMV or other viral infections and MS. An analysis of serum levels of neurofilament light chain, which serves as an indicator of the neuroaxonal degeneration seen in MS, rose only after EBV seroconversion.

Implications for MS

While identifying the central role of EBV in development of MS provides a path forward for future research on the neurological disorder, neither prevention nor a cure is available for MS today. A number of treatments have come online in recent years to modify disease progression, however.

MS takes two main forms, primary-progressive or relapsing-remitting. In 2017, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first and still the only disease-modifying therapy for primary-progressive MS, ocrelizumab. Delivered as an infusion, ocrelizumab also received approval for use in relapsing-remitting MS.

“Multiple sclerosis can have a profound impact on a person’s life,” said Billy Dunn, MD, director of the Division of Neurology Products in the FDA’s Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, in announcing the approval. “This therapy not only provides another treatment option for those with relapsing MS, but for the first time provides an approved therapy for those with primary progressive MS.”

Patients with the relapsing-remitting form of the disease have more options. Injectable therapies include interferon beta medications and glatiramer acetate. Infusions include ocrelizumab, natalizumab and alemtuzumab, which is

only available through restricted distribution under the FDA’s Risk Evaluation and Mitigation Strategy program because of its increased risk of autoimmunity, infusion reactions and malignancies. A number of oral therapies are also available for relapsing-remitting MS. Among them are fingolimod, dimethyl fumerate, diroximel fumarate, teriflunomide, siponimod and cladribine.

The USUHS/Harvard team’s research gives hope that MS could one day be a vanquished disease. “Currently there is no way to effectively prevent or treat EBV infection,” Ascherio said, “but an EBV vaccine or targeting the virus with EBV-specific antiviral drugs could ultimately prevent or cure MS.”

- Bjornevik K, Cortese M, Healy BC, Kuhle J, Mina MJ, Leng Y, Elledge SJ, Niebuhr DW, Scher AI, Munger KL, Ascherio A. Longitudinal analysis reveals high prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus associated with multiple sclerosis. Science. 2022 Jan 21;375(6578):296-301. doi: 10.1126/science.abj8222. Epub 2022 Jan 13. PMID: 35025605.