As the number of first-line treatments for Waldenström Macroglobulinemia increased, older adults experienced marked improvements in survival Among older patients, median progression-free survival improved from 28.3 months in the early era to 63.3 months in the modern era, according to a new study. Younger patients, on the other hand, showed almost no improvement in median progression-free survival between eras, the authors pointed out.

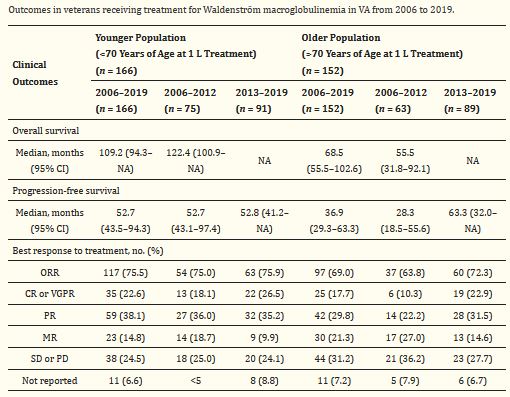

Click To Enlarge: 1 L: first-line treatment; CI: confidence interval; CR: complete response; MR: minimal response; NA: not available; no.: number; ORR: overall response rate; PR: partial response; PD: progressive disease; SD: stable disease; VA: Department of Veterans Affairs; VGPR: very good partial response. Source: Cancers (Basel). 2021 Apr; 13(7): 1708.

SALT LAKE CITY — Not much is known about Waldenström macroglobulinemia (WM), a rare type of cancer that originates in white blood cells. In the United States, only 1,000 to 1,500 people are diagnosed with WM each year. Yet over the last decade, patients diagnosed with lymphoid malignancies such as WM have benefited from the introduction of several new anticancer therapies—namely Bruton tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors like ibrutinib, acalabrutinib and zanubrutinib, as well as BCL2 inhibitors like venetoclax.

These therapies have joined existing treatments such as immunotherapy (rituximab), proteasome inhibitors (bortezomib, ixazomib, carfilzomib) and even older treatments such as bendamustine.1

Although none of these treatments can cure WM, the availability of more options with varying therapeutic targets—which reduces the likelihood of cross-treatment resistance—allows patients and providers to use numerous treatments throughout the disease course, prolonging the ability to control the disease and hopefully improving overall survival. A broader landscape of therapies also affords greater opportunity to personalize treatment depending on patient characteristics and tolerances.

Still, there is much to learn about how the introduction of newer treatments has affected real-world treatment patterns and outcomes among WM patients, particularly older adults. Only a small fraction of cancer patients is eligible and elects to participate in clinical trials, a fact that is even more pronounced in rare cancers such as WM. In addition, older adults, those with comorbidities and racial and ethnic minorities are frequently underrepresented in clinical trials. This creates an unmet knowledge gap that providers and patients must navigate as they consider how clinical trial evidence applies to them—a gap that a new study aims to help close.2

The study, published in the journal Cancers, followed 166 younger (ages 70 or younger) and 152 older (over 70) WM patients who received first-line treatment between January 2006 and April 2019 in the VHA. The researchers examined treatment practices and patient outcomes both before (2006-2012) and after (2013-2019) newer treatments were introduced.

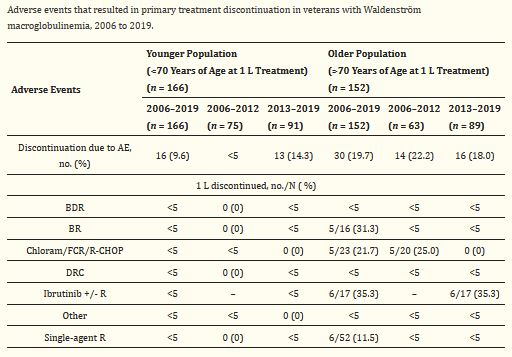

Click To Enlarge: 1 L: first-line treatment; AE: adverse event(s); BDR: bortezomib and dexamethasone +/− rituximab; BR: bendamustine +/− rituximab; Chloram: chlorambucil; DRC: dexamethasone, rituximab, and cyclophosphamide; FCR: fludarabine and cyclophosphamide +/− rituximab; no.: number; R: rituximab; R-CHOP: cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisone ± rituximab. Source: Cancers (Basel). 2021 Apr; 13(7): 1708.

“Studies of real-world practices and outcomes allow providers and patients to learn more about what treatments the broader community of providers is utilizing and what outcomes are achievable outside the confines of strict clinical trial protocols,” said study author Ahmad Halwani, assistant professor of medicine at the University of Utah and a staff physician and clinical researcher at the George E. Whalen Veterans Health Administration in Salt Lake City. “When real-world studies are conducted in settings such as the VA, they also provide insight into the practices and outcomes that occur in underrepresented patient groups.”

That study found that, during the modern era, the proportion of older patients with a complete response or partial response to treatment (known as the objective response rate) was higher (72.3%) than in the early era (63.8%). For younger patients, the objective response rate was about the same in both eras (75% in the early era versus 75.9% in the modern era). The researchers observed no change in the proportion of older patients who discontinued treatment due to adverse events.

Older adults also experienced marked improvements in survival as the number of first-line treatments increased. Among older patients, median progression-free survival improved from 28.3 months in the early era to 63.3 months in the modern era. Younger patients, on the other hand, showed almost no improvement in median progression-free survival between eras.

One possible explanation, Halwani noted, is that newer treatments are at least as effective as older regimens, if not more so, but are also often less toxic (and therefore more tolerable) to older patients. “This allows older patients, who would not have tolerated effective treatment previously, to now receive more effective treatments that they can tolerate better, hence leading to improved outcomes,” he said. “This also highlights the need to study symptom burden in both patient populations, something that our group is also looking into. While younger patients in the modern era seem to have a similar overall survival, it may be that they are now able to achieve this with fewer side effects from their treatment regimen.”

The study also is the first to describe real-world patterns of lab and biomarker testing rates in a cohort that includes both older and younger patients. All patients who received first-line treatments received hemoglobulin and platelet testing beforehand. About one-sixth did not receive immunoglobulin M (IgM) testing, a rate that did not differ significantly between eras. Although MYD88 mutation status screening, a predictor for survival and treatment response, is recommended as an essential workup in the 2016 National Comprehensive Cancer Network Guidelines, less than one-quarter of patients received MYD88 screening before beginning first-line treatment.

In hindsight, the researchers noted this finding was not particularly surprising. “This diagnostic and prognostic marker was only recently introduced into clinical practice and some of the patients in our study (even those in the modern era) were treated preceding its introduction to clinical practice,” said Halwani. “In addition, it historically takes years for these diagnostics to become highly adopted in clinical practice.”

In terms of treatment patterns, the study’s findings demonstrate the rapid adoption of evidence-based treatments for WM among older patients within the VHA. The initial utilization of combined dexamethasone, rituximab and cyclophosphamide (DRC) occurred during the same quarter as the publication of its Phase 2 clinical trial. The results also reveal a rapid uptake of ibrutinib, which was first utilized in the older population within the same month of FDA approval, as well as bendamustine with rituximab (BR) and bortezomib with rituximab and dexamethasone (BDR). Younger patients, meanwhile, tended to receive newer treatments even earlier, before evidence from clinical trials was published.

The researchers said they hope their study highlights the need to incorporate the collection, analysis, and reporting of real-world data into the daily clinical operation of all healthcare systems. “There is a tremendous opportunity to learn from real-world data to generate knowledge about patients, especially those underrepresented in clinical trials, as well as improve the quality and value of care delivered,” said Halwani. “While this will never replace clinical trials, it will serve as a necessary complement, allowing healthcare systems such as the VA to move towards a rapid learning healthcare system.”

- American Cancer Society. Key Statistics About Waldenstrom Macroglobulinemia. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/waldenstrom-macroglobulinemia/about/key-statistics.html

- Chien, H-C, Morreall, D, Patil, V, Rasmussen, KM, et. al. Treatment Patterns and Outcomes in a Nationwide Cohort of Older and Younger Veterans with Waldenström Macroglobulinemia, 2006–2019. Cancers. Published April 4, 2021. DOI: 10.3390/cancers13071708.