With a range of smoking cessation program, the VA is having some success reducing the percentage of veterans who use tobacco. Still, data show that veterans find it hard to quit, even when they have been diagnosed with lung cancer and continued smoking affects their overall survival.

WASHINGTON, DC — It’s long been recognized that servicemembers and veterans use tobacco at higher rates than the general population. According to the most-recent statistics, 29.2% of veterans reported tobacco use, with 21.6% of them favoring cigarettes. This number is even higher among veterans who had been deployed. Every year, the department spends tens of millions on smoking cessation programs—a fraction of the estimated billions spent treating tobacco-related illnesses.

According to a 2021 survey, VA is having some success with enrolled veterans. VA found that the rate of veterans enrolled in VA healthcare who identified as smokers dropped nearly 20% in 21 years, from 33% in 1999 to 13.3% in 2020. By comparison, the smoking rate for the general population in 2021 was 14.2%.

How much of that is due to VA’s cessation efforts and how much is due to smoking becoming less prevalent among the younger populations of veterans is unknown.

Regardless, helping a veteran quit smoking is never easy. Attempts to quit are more likely to fail than succeed. Studies have found that former smokers tried to quit an average of five to seven times before finding success. In 2018, the FDA found that, of the 55% of adult smokers who tried to quit in the previous year, only 8% were successful.

Consequently, VA has developed a large cadre of smoking cessation programs over the years to give veterans as many paths to quitting as possible.

There are the standards of medication and counseling. Nicotine replacement therapy, and medications such as bupropion and varenicline can help patients manage nicotine withdrawal. VA offers tobacco cessation counseling, in person or over the phone, to help patients cope with the tobacco-use triggers and make changes in their lifestyle to help them quit tobacco.

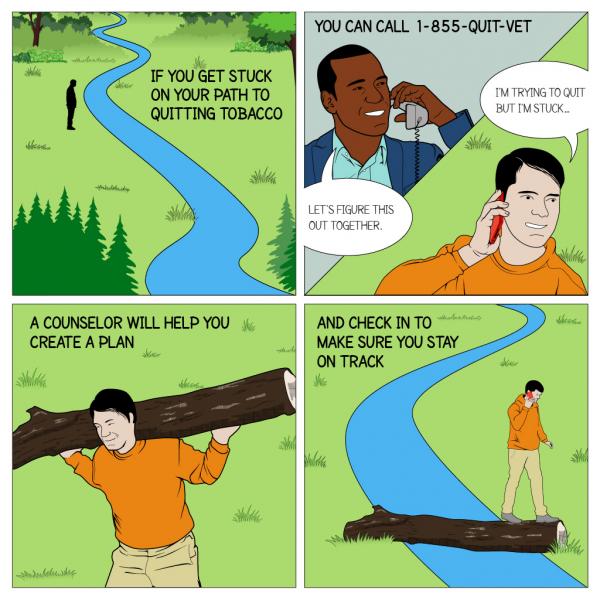

Over the years, technology has played an increasingly important role in cessation efforts. VA’s Tobacco Cessation Quitline (1-855-QUIT-VET) puts veterans in touch with counselors who can help them develop a cessation plan. SmokefreeVET is a text-based service that provides daily advice and support to veterans who are in the process of quitting. And the Stay Quit Coach is a mobile app designed with interactive tools to help veterans deal with urges.

How successful these mobile health programs are in helping veterans is still being examined. A study published last year in Nicotine and Tobacco Research found that, of a cohort of veterans subscribed to SmokefreeVET, more than 40% quit before the program’s completion and only 3.7% self-reported 30-day abstinence after six months. The vast majority of those who quit did so within the first week. Those who completed the program were more likely to have also been using smoking cessation medication.

Even patients who have an immediate medical incentive to quit are more likely to fail than succeed. In fact, specialist care referrals are less likely to be followed up on by the patient than those made by their primary care doctor.

A study published last year in Tobacco Prevention & Cessation found that of veterans who received smoking cessation referrals in the context of an acute illness, only 42% followed up compared to 68% percent of referrals made by a primary care provider.1

“The presence of an acute illness in isolation failed to impact program success,” the study notes. “However, while surgeon-initiated referrals were meager in number, the engagement rate approached that of primary care. This finding suggests that surgeons play a powerful role in influencing patient behavior that may be harnessed to augment success of existing cessation programs.”

Abstinence Difficult to Achieve

But while VA surgeons might be able to get patients started on the path to quitting, long-term abstinence is difficult to achieve.

Another late 2021 study appearing in the journal Chest involved a VHA dataset of patients with clinical Stage I non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) undergoing surgical treatment between 2006 and 2016. Persistent smoking was defined as continuing to smoke one year after surgery; that information was used to describe the relationship between persistent smoking and disease-free survival and overall survival.2

Of the 7,489 patients undergoing surgical treatment for clinical stage I NSCLC, 60.9% were smoking at the time of surgery and 58.0% continued to smoke at one year after surgery, according to the authors. Among the 39.1% of patients who were not smoking at the time of surgical treatment, 19.6% relapsed and were smoking at one year after surgery, the authors add.

Results indicate that persistent smoking at one year after surgery was associated with significantly shorter overall survival (adjusted hazard ration [aHR], 1.291; 95% CI, 1.197-1.392; p<0.001) but was not associated with inferior disease-free survival (aHR, 0.989; 95% CI, 0.884-1.106; P=0.84).

“Persistent smoking following surgery for stage I NSCLC is common and is associated with inferior overall survival,” the researchers concluded. “Providers should continue to assess smoking habits in the post-operative period given its disproportionate impact on long-term outcomes after potentially curative treatment for early-stage lung cancer.”

Because veterans are at a higher risk of developing lung cancer, VA has placed an increasing emphasis on lung cancer screening for patients who smoke. The VA Partnership to Increase Access to Lung Cancer Screening (VA-PALS) is a collaboration between the VA Office of Rural Health, Bristol-Myers Squibb Foundation, and the International Early Lung Cancer Action Program to increase veterans’ access to lung cancer screening. If found early, lung cancer has an 80% cure rate.

However, only a small portion of patients who agree to be screened receive treatment for smoking cessation. A study published last year in the Journal of General Internal Medicine looking at patients who were screened between 2014 and 2018 found that only 18.3% received medication or counseling, and only 1% received a combination of both. Of those receiving medication, only 1 in 4 received one of the most effective medications.3 Overall, only 5,400 of the 47,609 current smokers screened (11.3%) were successful in quitting.

- Maloney CJ, Kurtz J, Heim MK, Maloney JD, Taylor LJ. Role of procedural intervention and acute illness in veterans affairs smoking cessation program referrals: A retrospective study. Tob Prev Cessat. 2021;7:3. Published 2021 Jan 11. doi:10.18332/tpc/130776

- Heiden BT, Eaton DB Jr, Chang SH, Yan Y, Schoen MW, Chen LS, Smock N, Patel MR, Kreisel D, Nava RG, Meyers BF, Kozower BD, Puri V. The Impact of Persistent Smoking After Surgery on Long-term Outcomes After Stage I Non-Small Cell Lung Cancer Resection. Chest. 2021 Dec 14:S0012-3692(21)05082-0. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2021.12.634. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34919892.

- Heffner JL, Coggeshall S, Wheat CL, Krebs P, Feemster LC, Klein DE, Nici L, Johnson H, Zeliadt SB. Receipt of Tobacco Treatment and One-Year Smoking Cessation Rates Following Lung Cancer Screening in the Veterans Health Administration. J Gen Intern Med. 2021 Jul 19. doi: 10.1007/s11606-021-07011-0. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34282533.