Especially Common in Women Experiencing Military Sexual Trauma

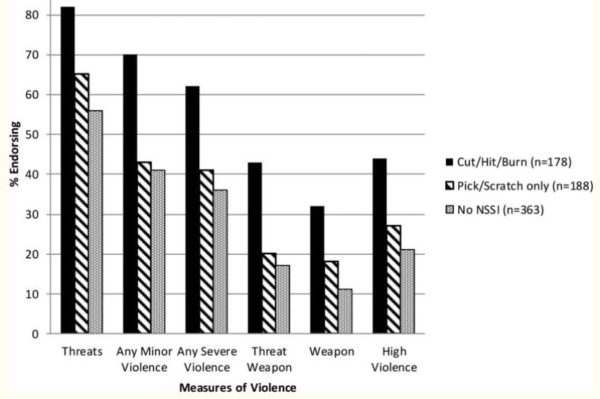

Percent endorsing past-year aggression and violent acts among help-seeking veterans with PTSD by NSSI status. Threats = Threatened to hit or throw something at a person. Any Minor Violence = threw something at a person; pushed, grabbed, or shoved a person; slapped a person. Any Severe Violence = kicked, bit or hit a person; beat up a person; threatened a person with a knife or gun; used a knife or gun. Threat Weapon = threatened a person with a knife or gun. Weapon = used a knife or gun. High violence = Thirteen or more minor and/or severe violent acts reported in the past year.

NEW HAVEN, CT — The VA has put significant focus on reducing veteran suicide rates over the last decades. But what about those who hurt themselves while stopping short of taking their own lives?

A recent study sought to evaluate the prevalence of lifetime nonsuicidal self-injury (NSSI) among U.S. military veterans and identify sociodemographic, military, psychiatric and clinical correlates associated with NSSI.

The report in Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy analyzed data from the 2019-2020 National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study, a contemporary, nationally representative survey of 4,069 U.S. veterans. Researchers from the VA’s National Center for PTSD, the VA Connecticut Health Care System and Yale University School of Medicine led efforts to measure outcomes which included lifetime history of NSSI, trauma history, lifetime and current DSM-V mental disorders and lifetime and recent suicidal behavior.1

Results indicated that the overall prevalence of lifetime NSSI was 4.2% (95% confidence interval=3.6%-4.9%). In addition, the authors noted that veterans who injured themselves over their lifetimes tended to be younger, female, non-Caucasian, unmarried or unpartnered and to have a lower annual household income.

Those veterans also “reported more adverse childhood experiences and lifetime traumas and were more likely to have experienced military sexual trauma,” researchers pointed out. “They also were more likely to screen positive for lifetime post-traumatic stress disorder, major depressive disorder (MDD) and substance use disorders and to have attempted suicide. Finally, lifetime NSSI was associated with current MDD, generalized anxiety disorder and substance use disorders, as well as past-year suicidal ideation.”

According to the authors, the study was the first to provide data on the epidemiology of NSSI in U.S. military veterans. “They suggest that certain correlates can help identify veterans who may be at greater risk for engaging in NSSI, as well as the potential prognostic utility of lifetime NSSI in predicting current psychiatric problems and suicide risk in this population,” they noted.

The results might have been somewhat unexpected, however, with past research focusing more on male veterans as being especially vulnerable to NSSI. Other studies have recognized the strong connection with military sexual trauma.

A 2018 report published in Psychiatry Research pointed out that NSSI has been understudied among MST survivors. Rocky Mountain Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center for Suicide Prevention researchers in conjunction with VA sought to describe characteristics of NSSI among MST victims. They also analyzed whether those veterans who engaged in NSSI were somehow different from those who never harmed themselves in terms of the severity of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and depressive symptoms, trauma-related cognitions, and recent suicidal ideation.

For this small study, participants were 107 veterans—65 females and 42 males—with a history of MST; about one-fourth of them had history of NSSI. Most participants who reported engaging in NSSI said they first hurt themselves following MST. In addition, researchers found that MST survivors with a history of NSSI reported more severe PTSD symptoms, recent suicidal ideation and trauma-related cognitions.

Severe Clinical Presentation

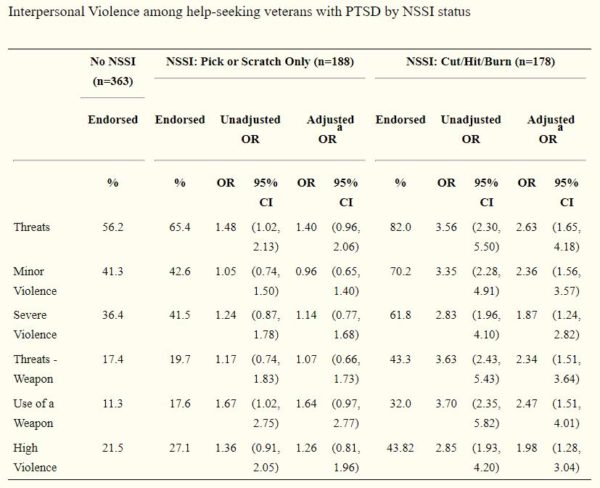

Note. NSSI = Nonsuicidal self-injury, OR=Odds Ratio; CI=Confidence Interval.

aAdjusted for age, race, marital status, employment status, socioeconomic status, combat exposure, presence of major depression, alcohol misuse severity, PTSD symptom severity, and difficulty controlling violence in past 30 days. The referent category for all odds ratios is Veterans without NSSI. Odds Ratios with confidence intervals that do not contain 1 are statistically significant at p<0.05

“NSSI was relatively common in the sample and was associated with a more severe clinical presentation,” the authors wrote. “Longitudinal research is needed to understand the development, maintenance and function of NSSI in MST survivors, especially as it pertains to risk for suicidal self-directed violence.”

A previous study conducted by researchers from the A Mid-Atlantic Region Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center (MIRECC), Durham, NC, USA

VA Mid-Atlantic Region Mental Illness Research, Education and Clinical Center (MIRECC in Durham, NC, the Durham VAMC and Duke University Medical Center defined NSSI as deliberately damaging one’s body tissue without conscious suicidal intent.

Those researchers emphasized that NSSI is “a robust predictor of suicidal ideation and attempts in adults.”

That report, published in Psychiatry Research in 2017, pointed out that NSSI has been associated with other-directed violence in adolescent populations but that the link between NSSI and interpersonal violence in adults is less clear.

“The current study examined the cross-sectional relationship between NSSI and past-year interpersonal violence among 729 help-seeking veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD),” the authors explained. “Veterans who reported a recent history of engaging in cutting, hitting or burning themselves were significantly more likely to report making violent threats and engaging in violent acts, including the use of a knife or gun, in the past year than veterans without NSSI.”

In fact, they said that NSSI was strongly linked with interpersonal violence after controlling for a variety of dispositional, historical, contextual and clinical risk factors for violence, including age, race, socio-economic status, marital status, employment status, combat exposure, alcohol misuse, depression, PTSD symptom severity and reported difficulty controlling violence.

The study strongly urged clinicians working with veterans with PTSD to review NSSI history when conducting a risk assessment of violence, stating that the findings have important clinical implications.

“Routine screening for a wide variety of NSSI behaviors, especially in Veteran Health Administration (VHA) psychiatric settings, is warranted,” the authors wrote. “Clinicians should be aware that NSSI is prevalent among male help-seeking veterans with PTSD regardless of age, race, SES, working status, or combat era. Previous studies indicate that NSSI is a robust predictor of suicidal ideation and suicide attempts in veterans with PTSD. Results from the current study indicate that the assessment of NSSI may also help in identifying those at highest risk for engaging in interpersonal violence.

“In particular, it has been recommended that clinicians working with veterans systematically examine risk and protective factors that have empirical support in order to improve decision-making. As such, the current study attests to the need for clinicians to assess NSSI history, and in particular a history of cutting/hitting/burning, when conducting risk assessments for violence as well as suicide.”

Researchers also advised that veterans who reported engaging in NSSI in the past year reported higher levels of PTSD symptoms and depression. More work is needed to examine the functions of NSSI in this population, they said.

- Kachadourian LK, Nichter B, Herzog S, Norman S, Sullivan T, Pietrzak RH. Non-Suicidal Self-Injury in U.S. Military Veterans: Results from the National Health and Resilience in Veterans Study. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2021 Oct 1. doi: 10.1002/cpp.2673. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 34599541.

- Holliday R, Smith NB, Monteith LL. An initial investigation of nonsuicidal self-injury among male and female survivors of military sexual trauma. Psychiatry Res. 2018 Oct;268:335-339. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.07.033. Epub 2018 Jul 27. PMID: 30096662.

- Calhoun PS, Van Voorhees EE, Elbogen EB, Dedert EA, Clancy CP, Hair LP, Hertzberg M, Beckham JC, Kimbrel NA. Nonsuicidal self-injury and interpersonal violence in U.S. veterans seeking help for posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2017 Jan;247:250-256. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.11.032. Epub 2016 Nov 27. PMID: 27930966; PMCID: PMC5191947.