WASHINGTON — Every aspect of VA hospitals has been affected by the ongoing pandemic, but emergency care and urgent care have been disproportionately challenged, according to a VA Office of the Inspector General report.

In its survey of 63 VA facilities, OIG found PPE shortages and staffing challenges common throughout hospitals. It uncovered additional difficulties in social distancing and isolating potential COVID-19 patients, as well as a particular concern about having up-to-date information on the coronavirus, for which emergency staff are front-line responders.

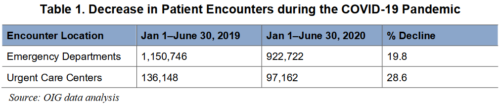

Despite being in the middle of a national health emergency, VA’s emergency departments saw fewer patients, at least during the first six months of the pandemic. From Jan. 1 to June 30 of last year, VA had 922,000 emergency department encounters and an additional 97,000 at urgent care centers. That represents a 19% decrease for ED visits and a nearly 30% drop at urgent care centers from 2019.

According to the OIG, this is consistent with reports from across the entire United States. healthcare system, indicating that patients were staying away from hospitals for fear of infection. The investigators noted that this could have public health implications in the future due to untreated illnesses and delayed screenings.

On the other hand, the reduction in patients might have been a blessing in disguise, as emergency departments were asked to swiftly shift their physical space to help accommodate hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

In the survey, emergency department and urgent care center directors noted two specific challenges with space and design: A small number of negative pressure or anterooms where COVID-19 patients could be isolated and small waiting rooms that did not allow for the social distancing of patients.

Instead, facility directors tried to make do. They installed tents to be used for COVID-19 screening, as well as additional emergency department beds; used parking areas to test, treat, and act as an additional waiting room; created separate entry points into the hospital; and repurposed entire areas of the hospital for emergency use.

All of the sites reported the ability to collect specimens for COVID-19 testing, with all but three able to conduct rapid testing. This allowed them to identify infected patients and limit the spread within the hospital. Several facility directors reported that they had expanded testing to patients who presented with non-COVID-19 symptoms.

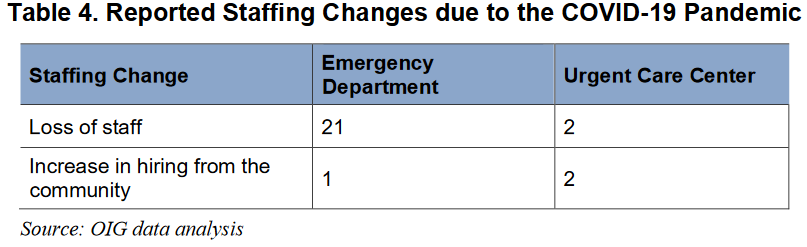

As departments have shifted space on the fly, they usually had to do so with fewer staff available. Of the 63 emergency departments and urgent care centers surveyed, 43 acknowledged staffing concerns, with the majority focusing on the need for additional registered nurses and technicians.

Staff Infections

Some of this has been from resignations and retirements, which have increased across the healthcare system during the pandemic. Emergency staff have also been hit with infections of their own. One facility reported that five physicians tested positive for COVID-19, while another reported several nursing staffers tested positive.

While all department directors said that they were monitoring staff for fatigue and burnout, the facilities in high-COVID areas were far more likely to see its effects. One director reported that staff had initially had a tremendous amount of fear and a high resistance to caring for patients with COVID-19 because of the possibility of transmission. Another noted that it would be difficult to find staff who had not been dealing with some level of burnout during the pandemic.

The report notes that the impact of COVID-19 on healthcare staff has been well-documented and that “regular screening of medical personnel involved in treating [and] diagnosing patients with COVID-19 should be done for evaluating stress, depression and anxiety.”

Despite these challenges, facility directors reported feeling well provided for by VA leadership, especially when it came to information on the best ways to treat COVID-19 patients.

“Emergency department directors stressed the importance of having up-to-date treatment guidelines,” the report states. “In emerging pathogens such as COVID-19, treatment data are often limited, and some are anecdotal. Several emergency department directors told the OIG that treatment guidelines were readily available, and they found it helpful to hear about other clinical and treatment experiences from colleagues in high-volume COVID-19 areas.

Directors also established innovative programs specific to their facilities to help support staff. The James A Haley VAMC in Tampa conducted regular meetings and town halls to ensure staff were educated and properly protecting themselves against the virus, while at the New Mexico VA Healthcare System, mental health providers were made available to talk anonymously with staff.

The report concluded that VA should take the lessons learned from these first six months, such as the need for a physical redesign and expansion of emergency departments, as a guide for how to prepare for the future.

“COVID-19 is reshaping the landscape of healthcare delivery worldwide, from how care is delivered on the front lines to overall operations of healthcare facilities,” the report states. “Moving forward, the operation and the delivery of emergent and urgent care will likely evolve further from previous models. VHA, as the nation’s largest integrated healthcare system, will be no exception.”