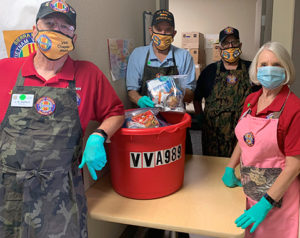

For 12 years, VA Sierra Nevada Health Care System in Reno has conducted an annual Homeless Veteran Stand Down, but planning provided challenging with the pandemic. Still, volunteers served 175 veterans this year at the event, shown here. The VAMC also is the site of a walk-in pharmacy clinic in its homeless day shelter. Photo from Oct. 11, 2020, VAntage Point blog

RENO, NV — Housing and mental health have always been intrinsically intertwined in the VA’s efforts to care for homeless veterans. As its original name—the Homeless Chronically Mentally Ill Program—made clear, the Health Care for Homeless Veterans Program focuses on providing services to veterans with serious mental health diagnoses.

Almost half of homeless veterans have struggles with mental illness and two-thirds battle substance use disorders. To meet the healthcare needs of these veterans, the VA created a Homeless Patient Aligned Care Team (H-PACT) model that has spread to 54 sites across the country. The model reduces barriers to care by offering open-access, walk-in access to integrated, one-stop mental health, housing and primary care services. The agency now reports that veterans engaged with H-PACTs have 31% fewer emergency department visits and 24% fewer hospitalizations.

Many veterans continue to live in areas not served by fully developed H-PACTs, however, prompting clinical pharmacists, particularly those specializing in mental health, to step up to provide more targeted services in their communities. Several of these pharmacist-led initiatives have met with significant success.

Most recently, a postgraduate year 2 psychiatric pharmacy resident at the VA Sierra Nevada Health Care System started a pharmacy clinic in Reno, Nevada. The Reno VA does not have an H-PACT, but it does operate an off-campus day shelter for homeless veterans that offers services as part of the Health Care for Homeless Veterans Program. Elizabeth Haake, PharmD, now a pharmacist at the Central Texas Veterans Healthcare System in Temple, TX, decided to locate the walk-in pharmacy clinic in the Capitol Hill day shelter.

The clinic operated for half a day each week. Haake provided a range of services and interventions under the supervision of Kelly J. Krieger, PharmD, a psychiatric clinical pharmacy specialist and psychiatric pharmacy residency program director at the Reno, NV, VAMC.

The clinic operated out of group room located near the shower and laundry facilities to encourage veterans using those services or at the shelter to meet with social workers to drop by. An analysis of the first five months of operation found that visits lasted five to 30 minutes and averaged just over four per day. Over the 18 days of operation in that period, the clinic served 52 homeless veterans in 77 encounters, according to a study published in Mental Health Clinician.1

Follow Up Increased

Of the 205 documented interventions, 47 involved medication reviews, 22 included mental health assessments, and 39 focused on patient education such as medication counseling, use of glucometer, and using VA benefits. Seventeen veterans obtained prescriptions for psychotropic medications. Haake made 34 referrals to primary care, mental health or specialty clinics and veterans follow through on 13 of those. Of nine referrals scheduled during visits, three were attended. The clinic increased follow up with VA providers by nearly 30% and reduced emergency department visits by almost 10% compared to the 30 days prior to a clinic-initiated intervention.

The clinic was well accepted by the social workers at the shelter who frequently referred veterans and a nurse practitioner joined the group of providers at the shelter during the period analyzed. “Looking forward, a psychiatric CPS will replace the resident, and as the clinic grows, other providers, including a psychiatrist and psychologist, will be recruited to join the CPS and the NP to provide the foundation for successful H-PACT establishment at the Reno VA,” Haake and Krieger wrote.

The Reno program demonstrated the feasibility of establishing mental health outreach to homeless veterans outside of or as a precursor to creation of an H-PACT. A mental health pharmacy clinic initiated by a second year psychiatric pharmacy resident in conjunction with the H-PACT clinic operated by the South Texas Veterans Health Care System in San Antonio provided clear evidence of cost savings and improved access for homeless veterans associated with integration of a clinical pharmacy specialist.2

Prior to the intervention, the H-PACT clinic included a primary care provider, registered nurse, licensed vocational nurse, psychologist, psychiatrist, and social worker. The psychiatrist worked at the clinic one day a week and typically saw six to seven veterans. The limited number of available appointments extended follow-up appointments out to eight or 10 weeks, limiting the psychiatrist’s ability to monitor and adjust medications on a timely basis. Compounding the problem, veterans in the H-PACT program could not be referred to a clinical pharmacy specialist in other outpatient clinics because policies mandated that all care for homeless veterans occur with the H-PACT.

The mental health pharmacy clinic added an additional four hours to the schedule on the same day the psychiatrist saw veterans. The pharmacy resident assessed patients in 30-minute visits, enabling an additional three veterans to be seen each week. Within three months, the addition of the resident reduced the wait time for veterans needing mental health medication follow up to between four and six weeks. Five percent of the visits were walk-ins.

Over a six-month period, the mental health pharmacy resident in San Antonio had 40 patient encounters with 21 veterans involving mental health pharmacotherapy evaluation. Interventions included identification of medication administration errors, medication adjustments, adherence education, and polypharmacy reduction. Estimated cost savings totaled $33,614.

Addressing Homelessness

The need for continued innovation in reaching and providing mental health services to homeless veterans remains, but significant progress has been made in improving the mental and physical health of these vulnerable veterans by reducing the number of former warriors without permanent domiciles through the Health Care for Homeless Veterans Program. In 2010, more than 74,000 veterans were homeless. By 2019, that number had been cut nearly in half to 37,878 through VA partnerships with communities across the country and coordinated governmental interagency efforts.

On October 1, the most recent community to end veteran homelessness in its midst celebrated its success in creating and deploying the infrastructure necessary to quickly identify and house veterans experiencing homelessness.

Kristine Lott, mayor of Winooski, VT, accepted the VA’s “Mayors Challenge to End Veteran Homelessness” in November 2019. Less than a year later, the town and surrounding Crittenden County, Vermont, had met its goal through cooperation with the White River Junction VA Homeless team, the Vermont Veterans Committee on Homelessness, and other organizations and joined 78 other communities and the states of Connecticut, Delaware, and Virginia that can boast success in finding permanent housing for all its veterans.

“Each one of the three states and 79 communities that has effectively ended veteran homelessness has worked closely with federal partners, like VA and used data to guide key decisions. Chittenden County reached this important milestone by following that same formula,” said VA Secretary Robert Wilkie. “Chittenden County’s achievement shows that by working together across all levels of government and in coordination with private and non-profit organizations, we can ensure that homelessness among veterans is rare, brief and non-recurring.”

The effort in Chittenden County and elsewhere to end homelessness among veterans reflects the continued commitment to improving access to healthcare and mental health services for all veterans through a variety of creative programs.

“Our Homeless Veteran team has done amazing work. This accomplishment demonstrates that the VA and its community partners are united and poised to provide a systematic, coordinated response to ensure homelessness is prevented whenever possible,” said Rob Scott, chief of Mental Health at the White River Junction VA. “Stable housing is such a critical component of both physical and mental health.”

- Haake ER, Krieger KJ. Establishing a pharmacist-managed outreach clinic at a day shelter for homeless veterans. Ment Health Clin. 2020;10(4):232-6. DOI: 10.9740/mhc.2020.07.232.

- Pauly JB, Moore TA, Shishko I. Integrating a mental health clinical pharmacy specialist into the Homeless Patient aligned Care Teams. Ment Health Clin. 2018;8(4):169-174. DOI:10.9740/mhc.2018.07169.