SAN FRANCISCO—Since the novel coronavirus pandemic hit Europe in early March and washed across the United States later that month, emergency department staff and neurologists have asked, “Where are the stroke patients?”

By April, they were asking another question of stroke patients who did present to the emergency department, “What are you doing here?”

COVID-19 appears to be driving two significant changes related to stroke. First, fewer people seem to be having them than usual. Second, some of the patients showing up with strokes are well outside the usual risk groups.

The VA has seen both impacts.

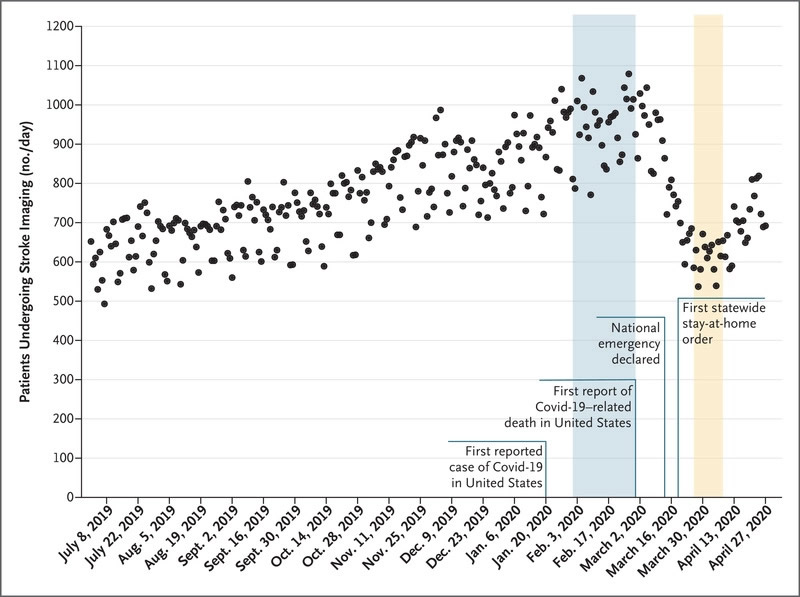

Daily Counts of Unique Patients Who Underwent Neuroimaging for Stroke in the United States, July 2019 through April 2020. Source: N Engl J Med. 2020;NEJMc2014816. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2014816

“In 40 VAMCs around the country, we have seen a modest decrease in stroke patients, perhaps a 20% decline. In the Brain Attack Coalition, we’ve seen a decline overall, more significant than that,” said Glenn Graham, MD, PhD, deputy national director for neurology, Office of Specialty Care Services, based at the San Francisco VAMC, and professor of neurology at the University of California-San Francisco.

Recent correspondence in the New England Journal of Medicine showed a 39% drop in stroke between February 2020 and imaging done in late March after a national emergency was declared. The study included 856 U.S. hospitals.1

Graham attributed the decline at the VA to changes arising from the pandemic.

To begin with, “elective surgeries are being held. Any time you do a procedure, there’s a small complication rate and that’s sometimes stroke related,” he told U.S. Medicine. Fewer surgeries, then, mean fewer strokes.

“A larger reason for the decrease is related to anxiety. We tell people that stroke is a medical emergency and to get to the hospital right away, but they may be afraid to go to the emergency department,” Graham said. “Patients may wait to come in if they have milder symptoms or not come in at all.”

Overcoming patient fear has been a focus of the Brain Attack Coalition this spring, he noted. The Coalition, which was organized by the National Institutes of Health, includes representatives from the major players in healthcare—hospital systems, providers, and patient advocacy groups.

“We’re trying to make sure that quality stroke care continues during these times and emphasizing that someone who suspects a stroke should get to a hospital right away,” he added.

Materials to raise awareness among veterans were expected to be finalized at the end of May. They included professionally produced videos and print materials.

COVID-19 Stroke

The VA has also seen some atypical patients for whom stroke was the presenting symptom of COVID-19.

“Statistically, we have relatively few patients in the database who have been admitted with transient ischemic attack (TIA) or stroke and COVID-19,” Graham said. “That may be an undercount, however.”

One case caught the medical team by surprise. The patient had stroke symptoms and “we did a CT angiogram of the head and neck and found a large clot leading to the brain,” Graham explained. While the imaging was not focused on the lungs, it revealed the ground glass opacity common in COVID-19 and the patient tested positive for the infection.

“We’ve seen small series reports in New York and Italy of large vessel thrombi, particularly in patients younger than the usual age seen in stroke, so we’re looking now to see if there has been an overall increase in veterans age 50 and younger, atypical patients for stroke,” he said.

Alarmingly, these young patients are experiencing the deadliest type of stroke, large vessel occlusions, which can damage large sections of the brain at once by obstructing major arteries.

Mount Sinai Health System in New York reported five cases of stroke in COVID-19 patients aged 33 to 49 between March 23 and April 7. That was seven times their usual rate for patients under age 50.2

“Judging from the limited literature and our experience, the SARS-CoV-2 coronavirus appears to be causing stroke in patients who do not have normal risk factors,” Graham noted. These patients are often three or four decades younger than most stroke patients. Like the VA case Graham described, they may not have any other symptoms of COVID-19, either.

That’s made VAMCs “extra cautious to image vasculature,” he said.

In Wuhan, China, about 5% of patients with the novel coronavirus had stroke, said Graham, citing a preprint study. Those patients were “very sick; they had aggressive COVID. What’s different in New York and what we saw, is that patients are not particularly sick otherwise. They present with stroke; they aren’t in the ICU already,” he emphasized.

Still, a recent study published in Stroke found that COVID-positive stroke patients were not just younger, they also had worse symptoms, and were seven times more likely to die than controls without the disease. The death rate was 63% in infected patients compared to 9% for stroke patients without the virus and a historical rate of 5%. The study included 32 virus-positive hospitalized stroke patients who received care at New York University hospitals in New York City and Long Island between March 15 and April 19.3

“Our findings provide compelling evidence that widespread blood clotting may be an important factor that is leading to stroke in patients with COVID-19,” said senior author Jennifer Frontera, MD, a professor of neurology at NYU Langone. “The results point to anticoagulant, or blood thinner therapy, as a potential means of reducing the unusual severity of strokes in people with the coronavirus.”

- Kansagra AP, Goyal MS, Hamilton S, Albers GW. Collateral Effect of Covid-19 on Stroke Evaluation in the United States [published online ahead of print, 2020 May 8]. N Engl J Med. 2020;NEJMc2014816. doi:10.1056/NEJMc2014816

- Oxley T, et al Large-Vessel Stroke as a Presenting Feature of Covid-19 in the Young. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:e60. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMc2009787.

- Yahi S, Ishida K, Torres J, et al. SARS2-CoV-2 and Stroke in a New York Healthcare System. Stroke. 20 May 2020. Online ahead of print. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.030335