WASHINGTON — Veterans seeking care from community providers could face even longer wait times under the MISSION Act than they did before the legislation went into effect, a VA Office of Inspector General report has concluded.

In the report released last month, investigators found that problems caused by staffing shortages and unnecessary red tape in the authorization process could become worse with the expected increase in veterans seeking non-VA care.

The MISSION Act, which was passed in June, overhauled VA’s community care policies in an attempt to cut down on appointment wait times. The legislation allows veterans who are facing long wait times for primary care, need care from specialists not available from VA or live prohibitively far from a VA facility to seek care from a private physician in one of VA’s community care networks. According to VA, the MISSION Act increased the number of veterans eligible for community care from 684,000 to 3.7 million.

While it’s too early to judge the success of the MISSION Act as a whole, the OIG report suggests that administrative deficiencies present before the legislation was passed will only be exacerbated, now that it’s gone into effect.

The report looked at 1.6 million veterans receiving care in VISN 8, which covers Florida, southern Georgia, Puerto Rico and the Caribbean. Investigators found that, in FY2018, veterans seeking community care had to wait an average of 56 days to see a physician. First veterans waited 10 days before the request was passed on to the facility’s community care department, then three days as the staff accepted the consult and then 43 days while the care was awaiting authorization by community care staff, after which an appointment would be scheduled.

Of these veterans, 39% were referred to community care because they would not have received a timely appointment with a VA physician. However, the staff at VISN 8 had no way of comparing wait times with community providers. Consequently, veterans waiting that average of 56 days had no way of knowing whether they were on the quickest path to care.

The report found that the main cause of this delay was a lack of administrative capacity. The audit team’s assessment of staffing levels showed that five of seven facilities were short on staffing needs. VA’s Office of Community Care called for a minimum of 313 administrative staff across all the facilities. The report found that the facilities were working with 237 administrative staff.

Another reason for the 56-day delay is that, from August 2014 through July 2018, the authorization and scheduling functions of approving community care were separated, with authorization being taken away from the facility’s community care departments and given to the OCC. In November 2017, it was determined that this caused needless delays in processing, and in July 2018 the functions were merged again at the facility level. However, at the time of the audit, six of seven facilities still had not merged the two functions. The reason given was that cross-training staff takes time, and the facilities were swamped with open consults.

One mitigating factor, according to VA officials, is that VISN 8 was contracting with Health Net—a third-party administrator tasked with maintaining the network of community providers at the time of the report. Health Net’s contract ran out in September 2018 and, according to VA, the department was throttling back on sending consults to them as early as January 2018. This meant that VISN 8’s community care departments were responsible for the majority of appointment scheduling during that time.

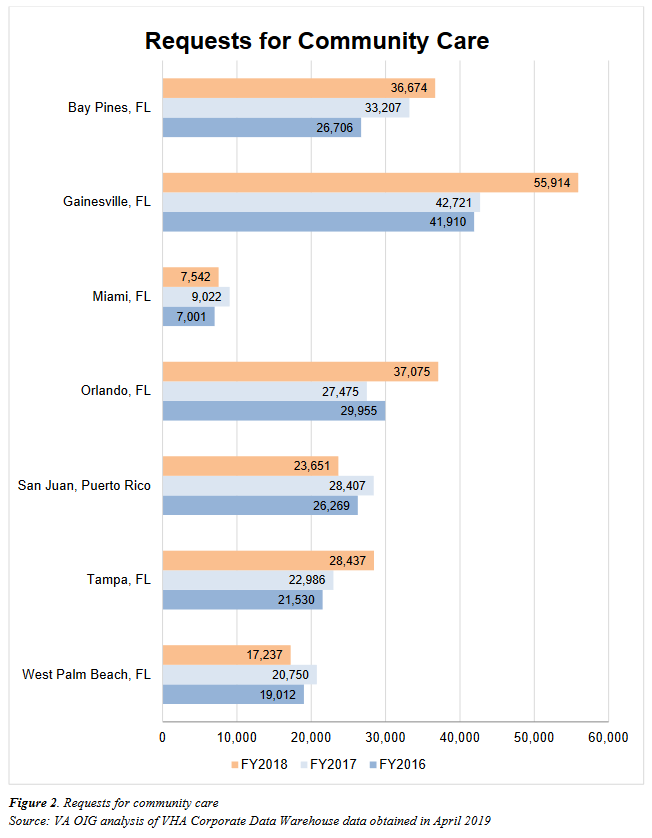

The effects of these administrative deficiencies will likely only grow as more veterans seek care under the MISSION Act, the IG report states. Early data shows an immediate growth in consult requests following the legislation’s passing.

Prior to the MISSION Act, VISN 8 facilities had an average of 3,350 consults per month sent to their community care departments. In the three months following the MISSION Act going live in June 2019, that average rose to 4,430 per month.

“Given the current workload and potential increase in patients eligible to receive community care, it is critical that VHA ensures sufficient staffing and efficient processing to effectively manage the workload,” the report states.

I have no doubt that processing these requests is a contributor to delays for community care, but these can be addressed by our Community Care departments and will doubtless get better. What Congress and perhaps the OIG do not realize is that for many specialties in many communities, even thought wait for VA care may exceed 28 days by a small amount (e.g. 30 or 35 days for an appropriate appointment), the wait in the community for comparable care is far longer. For example scheduling a new visit to an endocrinologist in the Phoenix area will typically require about a 3-month wait. Our endocrine division consistently has access for new patients within 35 (and usually in less than 28) days. Thus, patients sent out to community endocrinologists for consultation are waiting far longer for appointments than if they had elected to remain at our VA. Of course VA has no control of this delay.

This will consequently increase prescription volumes from the community for VA Pharmacies across the country and increase wait times. Pharmacy Services will not be able to recruit enough staff quick enough due to the red tape involved in requesting the staff required to meet the increased volume