More than 13,000 U.S. veterans treated in the VHA have a diagnosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia, which is associated with toxic military exposures. For the past 20 years, the VA has routinely treated patients with CLL diagnosis in accordance with clinical guidelines. Those who received recommended targeted therapies had longer overall survival.

Click to Enlarge: U.S. Army Huey helicopter spraying Agent Orange over agricultural land during the Vietnam War in its herbicidal warfare campaign. Source: Wikipedia

LONG BEACH, CA — U.S. military veterans with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) routinely received therapies in line with current evidence-based treatment practices over the past two decades, and those who were treated with targeted therapies had longer overall survival, according to a national VA study with more than 20 years of clinical data.

The retrospective analysis published in Clinical Lymphoma Myeloma and Leukemia described treatment patterns in the VA system over time and analyzed outcomes in U.S. military veterans diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia. The study authors were affiliated with the VA Long Beach, CA, Healthcare System.1

The authors sought to explore this topic, because “military exposures such as Agent Orange are associated with the development of chronic lymphocytic leukemia and lymphomas,” Helen Ma, MD, staff physician at the VA long Beach facility, told the Compendium of Federal Medicine.

Chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL) is the most common adult leukemia in Western countries. More than 13,000 veterans have the diagnosis.

“Patients can live with the disease for many years and may eventually need treatment,” said Ma, who also is a health sciences assistant clinical professor at the University of California, Irvine, in Orange, CA. “Veterans may have increased risk factors, e.g., exposures and age, that predispose them to the diagnosis of chronic lymphocytic leukemia.”

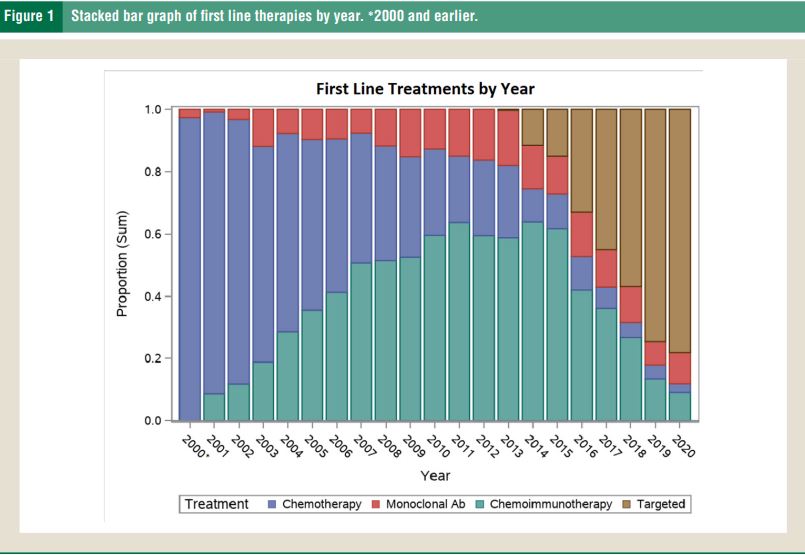

Click to Enlarge: Stacked bar graph of first line therapies by year. ∗2000 and earlier. Source: Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma and Leukemia, Vol. 24, No. 2, 77–82 Elsevier Inc.

The study authors noted that “exposure to Agent Orange may be associated with a younger age at diagnosis, but not with a worse overall survival.”

The study used VAHS medical records and examined data from predominantly adult male patients diagnosed with chronic lymphocytic leukemia that were managed in the VHA from January 1999 through December 2020. The final analysis included 16,331 patients with CLL. First line and subsequent treatment patterns were retrospectively trended over 20 years, and factors associated with survival were studied in both untreated and treated patients, according to the authors.

“We found that, in the national VA health care system, U.S. military veterans with chronic lymphocytic leukemia received therapies in line with current evidence-based treatment practices over the past 20 years,” Ma said. “Treatment with targeted therapies is associated with longer median overall survival both in the first line and relapsed/refractory setting.”

Overall, the analysis concluded that “prescribing patterns in the VA indicated that patients are receiving standard of care drugs in a timely manner.”

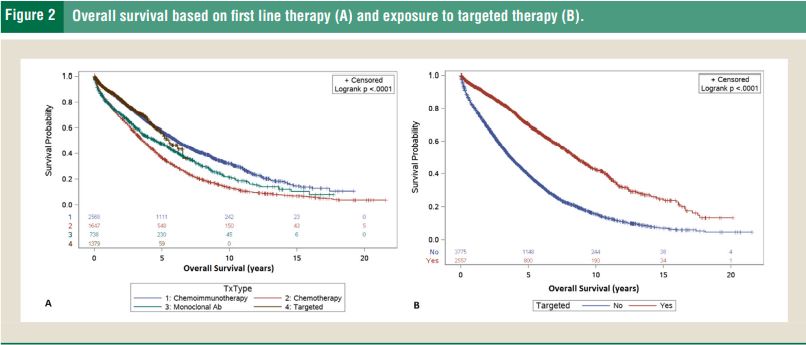

Click to Enlarge: Overall survival based on first line therapy (A) and exposure to targeted therapy (B). Source: Clinical Lymphoma, Myeloma and Leukemia, Vol. 24, No. 2, 77–82 Elsevier Inc.

The authors pointed out that “exposure to targeted therapies as either first line or in subsequent lines of therapy was associated with longer survival, resulting in median overall survival of 8.5 years (95% confidence interval (CI), 8.0-9.1) compared to 3.5 years (95% CI, 3.5-3.9) in patients who never received targeted therapy (P < .0001).”

The study also found that “targeted therapies given to patients who are not candidates for intensive chemoimmunotherapy may counteract poor prognostic factors, such as older age.”

Conversely, the analysis found that “patients who did not receive or require treatment for chronic lymphocytic leukemia were more likely to die from noncancer causes compared to those who received treatment for chronic lymphocytic leukemia, who were more likely to die from a hematologic malignancy.”

Individually Tailored

“All patients, both veteran and civilian, should be receiving first line, FDA-approved treatments for chronic lymphocytic leukemia, tailored for each individual patient,” Ma recommended.

Treatments for CLL included “targeted therapies such as Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors, B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) inhibitors and phosphoinositide-3 kinase (PI3K) inhibitors, which are increasingly used.” Data suggested that “patients who received BTK inhibitors in the first line or second line have a better survival compared to those receiving these targeted agents third line or later,” the study authors advised.

The “impact of these therapies on outcomes of chronic lymphocytic leukemia in U.S. military veterans, in whom lymphoid malignancies may be associated with unique epidemiological factors, has been unknown,” the researchers noted.

Among treated patients, the study found that the “median time to first line treatment was 1.9 years, and the median overall survival from initiation of treatment was 5 years.” The most common first line therapy was chemoimmunotherapy. However, first line treatment patterns varied over time.

The study reported that ibrutinib-based therapy was the most common first line targeted agent (n = 1,284, 93%).

That was followed by:

- Venetoclax-based therapy (n = 68, 5%),

- Acalabrutinib (n = 22, 2%),

- Combinations of ibrutinib and venetoclax on a clinical trial (n = 4, <1%), and

- Idelalisib, which was given first line due to concern about giving ibrutinib with warfarin (n = 1, <1%).

Median overall survival from initiation of first line therapy was 6.1 years for first-line chemoimmunotherapy, 5.5-plus years for targeted therapy, 4.6 years for monoclonal antibody and 3.6 years for chemotherapy, according to the report.

In addition, many patients “received targeted agents in subsequent lines of therapy.” In patients who received first line chemoimmunotherapy (n = 2,568), about half went on to receive additional therapy: chemoimmunotherapy (n = 465, 18%), targeted therapies (n = 441, 17%), monoclonal antibody (n = 258, 10%) and chemotherapy (n = 133, 5%), the authors explained.

In patients who received chemotherapy (n = 1,647), those who went on to second line chemoimmunotherapy were 22% (n = 369), chemotherapy 13% (n = 222), monoclonal antibody 11% (n = 180) and targeted therapies 6% (n = 105). In those who received targeted treatment, subsequent therapies included another targeted agent (n = 155, 11%), chemoimmunotherapy (n = 32, 2%), monoclonal antibody (n = 27, 2%), and chemotherapy (n = 17, 1%), the authors pointed out.

Of the 1,647 patients who received chemotherapy, 22% went on to receive chemoimmunotherapy, including:

- Chemotherapy,13% (n = 222),

- Monoclonal antibody 11% (n = 180), and

- Targeted therapies 6% (n = 105).

In those who received targeted treatment, subsequent therapies included another targeted agent (n = 155, 11%), chemoimmunotherapy (n = 32, 2%), monoclonal antibody (n = 27, 2%) and chemotherapy (n = 17, 1%), the authors pointed out.

In addition, among patients who received single agent monoclonal antibody (n = 738), the most common second line therapy was chemoimmunotherapy (n = 149, 20%), followed by targeted therapy (n = 101, 14%), chemotherapy (n = 51, 7%), and retreatment with monoclonal antibody after a treatment break (n = 18, 2%), the study team explained.

The study noted that “a significantly greater proportion of patients who received first-line targeted therapy (83%) did not receive or require second-line therapy compared to 49% of patients who received first-line chemoimmunotherapy; P < .0001.”

For healthcare professionals who are treating U.S. veterans with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, Ma recommended that “treatments for chronic lymphocytic leukemia and all cancers are rapidly evolving, so it is important to have a multidisciplinary, team-based approach.”

“There are many ongoing clinical trials to improve the outcomes of cancer patients, so I would encourage patients and their doctors to see if there are studies that would benefit them,” she emphasized.

Future investigations “should include prospective studies to understand treatment decisions, quantify duration of treatment and specify reasons for drug discontinuation,” study authors suggested.

- Ma H, O’Brien S, Gupta P. Treatment Patterns and Outcomes in U.S. Military Veterans Diagnosed With Chronic Lymphocytic Leukemia (CLL). Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk. 2024 Feb;24(2):77-82. doi: 10.1016/j.clml.2023.09.001. Epub 2023 Sep 7. PMID: 37743181.