Pressure injuries, commonly known as bedsores, often can be deadlier than the condition that causes patients to be bed-bound. Veterans are particularly at risk as a result of age, frailty and a high rate of spinal cord injuries. Preventing the condition and managing pressure ulcers when they occur has been an ongoing—and extremely expensive—battle for the VA.

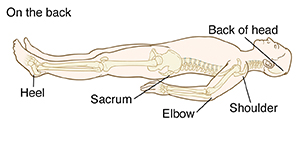

Click to Enlarge: Outline of person lying on back with bones visible. Pressure points: Back of head, shoulder, elbow, sacrum, and heel. Source: Veterans Health Library – VA

HANOVER, NH — For 60,000 Americans each year, the illness or injury that sent them to a hospital or nursing home will prove less deadly than the pressure injuries they acquire while bed-bound at the facility. Pressure injuries, which are largely preventable, affect approximately 2.5 million patients, cost the U.S. healthcare system an estimated $26 billion annually and rank among the top 10 causes of death in this country.

Veterans are particularly at risk as a result of age, frailty and a high rate of spinal cord injuries (SCIs). Nearly one-third of patients with spinal cord injuries develop pressure injuries (PIs) within a year of the injury occurring. Further, these wounds often do not resolve quickly upon discharge from a hospital. A recent study by researchers at the VA North Texas Health Care System in Dallas found that nearly half of grade 3 or 4 pelvic PIs in veterans with SCIs had not healed 12 months after discharge.1

Servicemembers injured in combat also face an increased risk of pressure injuries, also known as pressure ulcers or bedsores. A team at the University of Washington School of Nursing noted that, under operational conditions, “it would be expected that casualties would suffer skin damage within 2 to 5 hours.”2 Once those casualties arrive at a hospital, those PIs will require prompt, consistent attention.

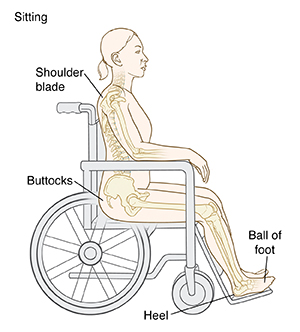

Click to Enlarge: Outline of person sitting in wheelchair with bones visible. Pressure points: Shoulder blade, buttocks, ball of foot, heel. Source: Veterans Health Library – VA

Even without the challenges of spinal cord injuries or rugged environments for initial care, veterans run a significant risk of acquiring PIs in hospitals and nursing homes—and both the VA and Congress have taken note.

The 2022 congressional appropriations bill included funding for the VA to adopt the International Guideline for Prevention and Treatment of Pressure Ulcers/Injuries. “Given the impact of PIs in U.S. VA facilities, the VA appropriations bill recommends incorporating best practices for PI prevention, specifically the Standardized Pressure Injury Prevention Protocols (SPIPP) checklist,” said members of the National Pressure Injury Advisory Panel (NPIAP) in an editorial in Advances in Skin & Wound Care.3 “The SPIPP checklist is a one-page tool based on the International Guideline to implement key components of prevention including skin check and risk assessment, repositioning, moisture and incontinence management, support surfaces, and nutrition.”

In addition, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) “recently added pressure injury to a spending tracker, so we can begin to see what studies are funded in the topic across institutes,” NPIAP Immediate Past President William Padula, PhD, told U.S. Medicine. “In contrast, DOD has earmarked up to $20 million that can be spent on pressure injury specific studies through the PRMRP funding mechanism. So far, they have not maxed spending at that threshold, and tend to hover in the range of a few million dollars in support for research across several health technologies.”

It’s no wonder PIs have captured the attention of lawmakers and funding agencies. Padula, who is also an assistant professor of Pharmaceutical & Health Economics in the School of Pharmacy and a fellow in the Leonard D. Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics at the University of Southern California (USC) in Los Angeles, said that the U.S. healthcare system spends $1 million on PIs every 20 minutes.

“The financial resources to implement SPIPP are what the VA appropriations bill covers,” added Padula and his NPIAP colleagues. “There are separate budget items in this large bill to pay for personnel for items beyond PI care, such as medication management and infection control. This type of budgeting helps PI care be financially sustainable in VA facilities.”

Multiple Ways to Reduce PIs

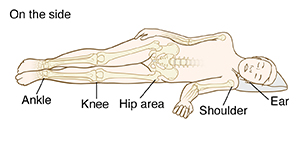

Click to Enlarge: Outline of person lying on side with bones visible. Pressure points: Ear, shoulder, hip area, knees, ankle. Source: Veterans Health Library – VA

The VA began focusing on reducing pressure injuries well before the recent funding, and continues to introduce a variety of measures to prevent these wounds. A team at the VA National Center for Patient Safety at White River Junction, VT, and the VA’s Pressure Injury Prevention and Management team in Washington, DC, introduced a 12-month virtual breakthrough series (VBTS) collaborative to tackle PI prevention in 2016 and then expanded the program to 28 acute and long-term care facilities in the VHA.4

The program included the VA SKIN Bundle and a project workbook. The VA SKIN bundle included assessing skin and risk status on admission and periodically afterward, using select surfaces and devices to relieve pressure, turning and repositioning, incontinence management and nutrition and hydration assessment and intervention.

Those step match well with the NPIAP’s SPIPP which emphasizes assessment of risk and skin tissue, preventive skin care by managing moisture and incontinence, redistribution of pressure and nutrition.

Each facility’s team had some flexibility in choosing the interventions they would implement. The teams implemented 23 unique interventions, 10 of them from the VA Skin Bundle, with each team selecting an average of four interventions. After education, the most common interventions introduced were bedside steps such as use of pressure-relieving boots, specialty mattresses and device dressings.

The aggregated rate of PIs declined from 1.0 to 0.8 per 1,000 bed days. In the long-term care units, the PI rates dropped 50%, from 0.8 to 0.4 per 1,000 bed days. “Clinically focused changes at the bedside may be what contributed to the reduced [facility-associated pressure injury] rates,” the researchers said.

Padula said the biggest game-changers since the International Guidelines were published in 2019 are sub-epidermal moisture scanning to predict cellular deformation before skin damage occurs and that timing of repositioning of patients does not need to be less than four hours if patients are moved consistently. A recent study of 1,100 patients in nursing homes found that cueing staff to reposition patients by using a wireless patient monitoring system that displayed the need for repositioning on monitors led to PIs dropping from 5.24% to zero, and that compliance was best (95%) at four-hour intervals.5

- Champagne PT, Tzen YT, Wang J, Bennett B, Van Beest D, Tan WH. Predictors of one year pressure injury outcomes in hospitalized spinal cord injured veterans with one stage 3 or 4 pressure injury. J Spinal Cord Med. 2023 Feb 6:1-7. doi: 10.1080/10790268.2022.2158290.

- Bridges E, Whitney JD, Burr R, Tonentino E. Pressure Injury Mitigation in Prolonged Care: A Randomized Noninferiority and Superiority Trial, Military Medicine, 2023 April; usad121.

- Padula WV, Black JM, Garcia A, Mishra MK. Congress Takes a Positive Swing at an Unsung Public Health Crisis: Preventing Pressure Injuries in Veterans Affairs Facilities. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2023 Mar 1;36(3):123-124. doi: 10.1097/01.ASW.0000903964.14644.66.

- Zubkoff L, Neily J, McCoy-Jones S, Soncrant C, Young-Xu Y, Boar S, Mills P. Implementing Evidence-Based Pressure Injury Prevention Interventions: Veterans Health Administration Quality Improvement Collaborative. J Nurs Care Qual. 2021 Jul-Sep 01;36(3):249-256. doi: 10.1097/NCQ.0000000000000512.

- Yap TL, Horn SD, Sharkey PD, Zheng T, Bergstrom N, Colon-Emeric C, Sabol VK, Alderden J, Yap W, Kennerly SM. Effect of Varying Repositioning Frequency on Pressure Injury Prevention in Nursing Home Residents: TEAM-UP Trial Results. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2022 Jun 1;35(6):315-325. doi: 10.1097/01.ASW.0000817840.68588.04.