WASHINGTON, DC — Rural veterans with serious mental health issues face a disproportionate challenge when seeking mental healthcare services from VA, according to a new report from the Government Accountability Office (GAO).

Not only are rural veterans waiting longer to get an in-person appointment, but also face barriers to receiving telehealth care. This should be concerning for VA, GAO investigators noted, because rural veterans tend to have higher rates of serious mental illness and a higher incidence of suicide than their urban counterparts.

The report also found that VA does not currently have an adequate way of tracking the effectiveness of intensive mental healthcare programs on veterans in rural areas.

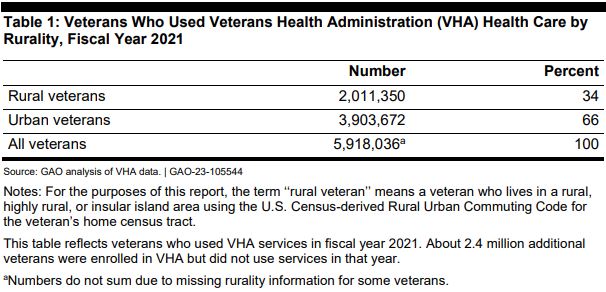

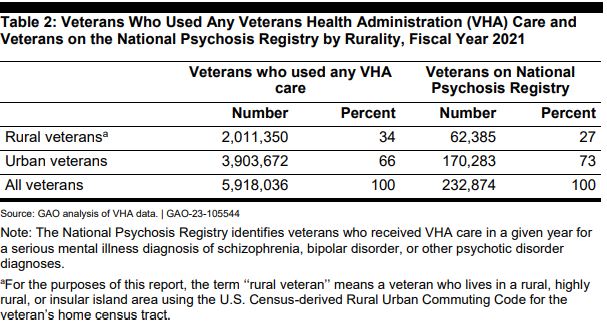

Of the 8.3 million veterans enrolled in VA healthcare, about one-third lived in a rural area in 2021. According to data from VA’s National Psychosis Registry, fewer veterans in rural areas received intensive mental healthcare for serious mental illness than urban veterans compared with their overall population distributions. Veterans with these types of diagnoses also received VA care at a lower rate than rural veterans in general. This suggests that those veterans are either choosing not to receive care at VA, or failing to receive care at VA.

“It is important that veterans with serious mental illness are able to access intensive mental healthcare because research indicates that inadequate access to mental healthcare leads to under-treatment and negative health consequences,” GAO wrote in its report. “Veterans with serious mental illness have a lower life expectancy than veterans who do not have such illness. … Research indicates that on average, the lives of veterans with serious mental illness are shortened by approximately 10 years.”

Some of the reasons for the difficulty of rural veterans to receive care have long been documented. There are fewer mental health professionals in rural areas, a fact exacerbated by the nationwide shortage in specialty physicians. VA facilities are spread farther apart. And gaps in high speed internet access in rural areas can sometimes rule out telehealth as an alternative.

The report also found that intensive mental healthcare programs might be especially more difficult for rural veterans to access.

VA data showed that 90% of VA facilities that offered Mental Health Intensive Case Management Programs served mostly urban veterans, and that only 18% of the veterans who used VA’s Psychosocial Rehabilitation and Recovery Centers were rural. Data also showed that 67% of VA facilities that offered Rural Access Network for Growth Enhancement programs served fewer rural veterans than urban veterans in 2021.

VA’s Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention told GAO that the guidelines for their mental healthcare programs are focused on providing care to all veterans and that, if a hospital or VISN identifies a need, they are supportive of initiating new outpatient programs to support those needs.

The GAO report found this to be a difficult, if not impossible, way of growing new mental healthcare programs for rural veterans.

“Without targeted guidelines that include specific parameters for establishing outpatient programs, the responsibility to justify the need for programs falls on individual healthcare systems,” the GAO investigators wrote. “Justifying the need for new programs can be difficult, particularly for rural-focused treatment programs.”

One key component of justifying a new program is data, and that can be lacking when it comes to rural veterans and VA healthcare utilization. In order to show how rural veterans are utilizing VA’s intensive mental healthcare services at a disproportionately lower rate, GAO was required to go to several data sources. This is because VA does not directly track utilization rates of these services by rurality.

“VHA has focused on comparing data on VHA healthcare systems with national averages, but does not analyze its data to compare rates between rural and urban veterans,” the report noted. “[Office of Mental Health and Suicide Prevention] officials said they do not analyze utilization or performance data by rurality because it is not required nor considered a priority by VHA.”

According to VA officials, because there were few programs targeted specifically to serving veterans in rural areas, there “is not a need to analyze access for rural veterans” and that their analyses are focused on all veterans nationally.

However, officials from several VISNs told GAO that they wished VA would analyze the data by rurality. VA officials agreed with the GAO’s recommendation and are exploring easy to incorporate rurality data in its evaluations for intensive mental healthcare programs.